What Could Lee See at Gettysburg?

A NEW METHOD OF CONSIDERING HISTORY

A Sense of Where You Are

by Anne Knowles

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

Early in his career one of our finest writers, John McPhee, wrote a memorable book about Bill Bradley called A Sense of Where You Are. In it, the writer developed an idea that Bradley, the best college basketball player in the country, succeeded because of his “extraordinary range of vision.” This constant and accurate sense of where he was in relation to the shifting patterns of his teammates, the opposing players, and the basket gave him an edge as important as any physical talent.

Lee on his horse Traveller.

It is this same idea that Professor Anne Knowles now takes into a fascinating new approach to history. Robert E. Lee, she argues, did not have a clear sense of where he was, and paid the price for it. That is, his limited understanding of the battlefield topography was a significant influence on the decisions he made during those three days at Gettysburg. Had he known more accurately where the Union positions were, for example, he might have endorsed Longstreet’s recommendation to swing south and attack the Union from behind. If we don’t stand where he stood and see what he saw, Prof. Knowles argues, then we really don’t get it.

In the essay “What Could Lee See at Gettysburg?” Prof. Knowles looks at Gouvernour Kemble Warren’s experience mapping the Sioux Territory as well as Lee’s background on the Mississippi River and in the Mexican-American War. She sets the battle in context and finds that Lee took his men into Pennsylvania “without [reliable] geographical information,” and paid a price for it.

There is a deep well of wisdom in Prof. Knowles’ approach. A growing number of scholars are discovering that we are all like Robert E. Lee: each of us is influenced by our geography. Richard Florida, Jared Diamond, Robert D. Kaplan and Benjamin Schwarz are just a few of the people measuring how the powers of place can affect our cities, our careers, our health, our food, and much more.

Perhaps equally important is Prof. Knowles’ conviction that only a collective approach to history – where many disciplines work together – can begin to approach recreating an accurate representation of any event.

I strive to write spatial narratives, which may hover over a given time or place to give a broader view that explains the geographical context of events.

When I taught for a week at the Navy War College, there was a vote for the most valuable lesson; the SEALs and SWICs unanimously chose the “Geography is Destiny” lesson plan. You can see why – in any battle, thorough knowledge of the terrain is going to provide one side or the other an advantage.

My cadets instantly see the usefulness of geography. We apply it to John Steinbeck and Barbara Kingsolver as well as the cadets’ home towns, Omaha Beach, the Kingdoms of Benin, and the success of Google. There is almost always something of value to gain when you add a consideration of place into the mix..

GIS, or Geographical Information Systems, is an approach to history that uses new technologies in an effort to take history beyond the book, into new representations and new forms of analysis. This is technology impacting the traditional study of history. The idea is to use computers to change how we view people and events, to experiment with different ways of organizing historical data. GIS and “spatial histories” have been developing over roughly a decade and a half. A densely written 2008 collection of essays entitled Placing History (which Prof. Knowles edited) is the first book I can find to set forth this viewpoint. One of the essays, by Peter K. Bol, describes GIS as “a platform for organizing data with temporal and spatial attributes – population, tax quotas, military garrisons, religious networks, religious networks, regional economic systems, family history, and so on – representing them graphically and analyzing their relationships.” Extremely ambitious. You can begin to see how these historians think when you read some of Richard White’ Foreword to Placing History:

The map is good at representing some kinds of space but not very good at tracing relationships through time. The historical form – the narrative – is not very good at expressing spatial relationships. Relationships that jump out when presented in a spatial format such as a map tend to clog a narrative …

GIS is a much larger methodology than just using geography – it incorporates new mapping software and datasets, adding quantitative history to narrative history in ways I don’t really understand. This much I do know: once you see the pervasive power of place, you begin to see it everywhere. I have listed in the lesson plans a number of topics with links to the use of geography in a wide array of circumstances.

In this interview and in the following excerpt, Prof. Knowles uses the methods of GIS to cast new light on this most familiar battle and the way decisions were made. She discusses the general tenets of GIS as well as the specific lessons for us waiting in a new look at the three fateful days of Gettysburg.

Interview with Prof. AnnE Knowles

1. What is “quantitative history”? How does it complement or contrast with narrative history?

I wouldn’t make this distinction. History is the study of the past. There are many ways to do historical research, including quantitative and qualitative methods, which one can also think of as being to varying degrees textual, visual, or numerical. Geographical approaches to history tend to draw on more than one method to answer both historical and spatial questions. As for narrative, that word refers to how one writes, not one’s method of investigation. I strive to write spatial narratives, which sometimes describe and explain events (this is what most people think of as narrative history) but may also hover over a given time or place to give a broader view that describes and explains the geographical context of events.

2. How can you explain Geographical Information Systems (GIS) as a subset of quantitative history? What is a GIS database? What new techniques have allowed us to understand the “historical construction of space”?

Historical GIS studies are so varied that they really shouldn’t be categorized as a subset of quantitative history. I would call historical GIS a trans-disciplinary method that can be quantitative or qualitative or both. As a digital framework for locating people, places, historical conditions, and events, a GIS is fundamentally quantitative because it assigns location according to geographical coordinates that are linked to a mathematical projection that transforms the three-dimensional sphere of the Earth into a two-dimensional plane. A GIS database may also contain quantitative information, such as census data, land values, and numerical codes for other kinds of information.

But a GIS database can also contain many kinds of qualitative information, such as the languages people speak, the emotions associated with particular places, the materials from which buildings were made, and so forth.

The GIS databases typically used in historical research consist of a spreadsheet, or a relational database, that contains “attributes” or characteristics that are linked to the locations of the places, people, or regions you are studying.

This project has made me a great believer in the value of interdisciplinary research.

A GIS project may also include what are called “raster” layers, which may be satellite images or scans of historical maps or layer of terrain elevations – any information contained in a grid. One of the great things about GIS is that you can layer different kinds of information that apply to the same geographical space and display, or analyze them, together. “The historical construction of space” is a huge subject! But a few basic techniques have proven really useful in visualizing past landscapes and analyzing their structure. One is using digital scans of historical maps that you then “georeference” so that they align with actual locations on the ground. If you georeference a series of maps that show the same region at several points in time, you can then use transparency to make each period appear in turn, so that you can see change over time. You can also digitally trace, or extract, particular features from georeferenced historical maps to combine in a GIS database. For example, if you had maps of the highway system in Los Angeles in, say, 1950, 1970, and 1990, you could trace the lines and combine them in a single map in GIS to show highways’ tremendous growth and how it is related to the explosion of LA suburbs.

3. One of the premises of your article is that Robert E. Lee might have made an entirely different set of decisions had he seen the battlefield topography clearly, from every angle. Because his view was limited, so was his decision-making. What might he – or McLaws, Warren, or Longstreet, or any of the commanders – have done differently?

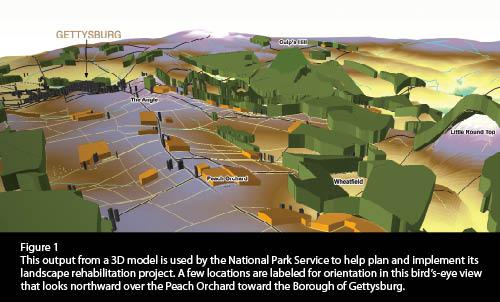

I am currently working with a number of researchers to create a more detailed digital rendering of the battlefield, with troop positions and (we hope) 3D views from a number of viewpoints to assess the limits on commanders’ views at a number of decisive moments. It is easier to estimate what they could not have seen, and to assess the wisdom or daring of the decisions we know they made, than to answer the counterfactual question of what they would have done differently had they had perfect information about the battlefield and the disposition of the enemy. If Robert E. Lee had been able to see the entire battlefield from every angle, he would not have been a Civil War general – he would be a 21st-century general operating drones from a fully equipped digital war room with live-feed, high-resolution, fixed satellite imagery and radar and so on.

If Lee had looked longer and harder, from more vantage points, at the Union position … he might have been more willing to swing south below the Round Tops to attack the Union from behind.

In the spirit of your question, I think, is the question of what Lee or other commanders might have done differently had they known somewhat more than they did. I’m inclined to believe that if Lee had looked longer and harder, from more vantage points, at the Union position at Gettysburg on Day 2 or even Day 3, with better scouting information about the strength of the Union forces, he might have been more willing to follow Longstreet and Hood’s recommendation to swing south below the Round Tops to attack the Union from behind, rather than making frontal assaults from problematic positions.

A more typical and limited view at Gettysburg, obscured by hills and trees.

Photo: Hundredfold Farms

4. For young scholars, what is the most accessible way to understand and apply the “added value” of GIS to conventional narrative histories?

The greatest single value GIS adds to history is that it situates history in the places where it happened. Working with GIS makes you very aware of physical circumstances, of distance and proximity, of obstacles and avenues. Combined with fieldwork, it brings a heightened sense of the physical reality of historical places that improves one’s ability to imagine, and so to write, vividly.

5. Iwo Jima is often cited — at least it is in my classes – as a clear example of battlefield geography being battlefield destiny. What are other historical battles where an outcome might have been different had topography been fully understood?

Custer’s last stand jumps to mind, and the Battle of Saratoga in the Revolutionary War.

I see the addition of sound, and analyzing what people may or may not have been able to hear, as an approaching frontier in historical research.

6. Now that modern militaries have satellites and drones, is military science entering a new age of near-perfect geographical awareness? Will there be fewer and fewer tactical errors due to limited knowledge of the battlefield/ Will there even be conventional battlefields in future wars?

Great questions. I have a sense from people I have met from West Point that geographical training is more important than ever in educating officers for the field.

While digital systems, including GIS, provide enormous amounts of tactical information, the speed of warfare is also changing, with decisions made in a click that can have enormous consequences. Warriors have much better knowledge of terrain, but since Viet Nam it has become increasingly difficult to know who the enemy is and how to stop them decisively. Machines still cannot provide all the intelligence commanders need to avoid errors.

7. How much does “aurality” have to add to our understanding of these great battles?

So much! I see the addition of sound, and analyzing what people may or may not have been able to hear, as an approaching frontier in historical research, which a few pioneers are already working on today. I also think scholars will soon be adding voice to their digital interpretations of the past, including military history.

Since Viet Nam it has become increasingly difficult to know who the enemy is and how to stop them decisively.

The eye – the human mind – still struggles to read text and visual images. Our brains jump from one more to the other, with momentary disconnects between each kind of thinking. Movies grab and hold us partly because simultaneous sound and sight simulate our experience of the real world. Historical interpretation should strive for that simultaneity.

8. What three things would you like the new generation of college students to take away from your work?

Learn digital technologies, but don’t let yourself be entirely beguiled by how “cool” they are. Think critically about what they genuinely add to your understanding and what they conceal or cannot show. Don’t mistake “cool” for “real.”

Read, read, read. Understanding the past is a never-ending quest, because we can never, ever recapture it entirely. The more you read about the historical subjects that interest you, the better you will be able to think about them from your own perspective.

Keep an eye out for historical maps. Maps contain kinds of information that no other historical sources contain. And try making your own maps, to keep track of complex events, as a graphic form of note-taking, and as a way to present your findings. Maps enrich every step of historical research and story telling.

9. Since you wrote this, has the field of study changed?

GIS generally has passed through at least two technical generations since I wrote “What Could Lee See at Gettysburg.” There are now excellent freeware GIS programs; 3D and virtual reality programs are more available to ordinary computer users; GoogleEarth and GoogleMaps have made maps and mapping much more common; and historical GIS continues to grow.

“The historical construction of space” is a huge subject!

There are now many historical websites with all kinds of fascinating information and images. But it’s still not easy to do really innovative, revelatory HGIS, because doing that requires having a question no one has asked before and finding a compelling way to answer it.

10. What new directions do you hope GIS will take you (and other scholars)?

Most ground-breaking GIS projects require collaboration, because they are labor intensive and call on a range of skills. I hope the new generation of historical scholars will retain the strong focus of independent scholarship while being more open to collaboration with other historians, geographers, computer scientists, and graphic artists to develop deeply researched, visually powerful new explanations of important historical events. Since “What Could Lee See,” I have been working with a team of historians and geographers studying the geographies of the Holocaust. This project has made me a great believer in the value of interdisciplinary research, if everyone involved can let the members of the team play to their strengths and all contributions can be valued. We have so much to learn from one another.

Pickett’s Charge, disastrous for the South, as re-enacted at the Battle of Gettysburg’s 145th anniversary.

Review “What could lee see at Gettysburg?”

Lord Wellington famously asked that no one ever attempt to write a history of the Battle of Waterloo. If you were not there, he argued, you cannot possibly understand all that happened; it is better to leave it alone than to disrespect the lives lost by portraying it incompletely.

Ann Knowles’ 9,000-word essay, “What Could Lee See at Gettysburg?” (the full text of which appears in the anthology Placing History) is a pioneering look at a new method with which we can make our histories more accurate. The new perspective she brings is a broad and deep view of the many ways geography influences us. Scholars have debated several key points about the three-day battle that changed the war, in particular why Lee chose to attack the Union in a frontal assault (the fateful Pickett’s Charge on Day Three).

By closing reading the topography and lines of sight as they existed that day, Prof. Knowles and her team of collaborators reveal valuable new insights. Yet Prof. Knowles mini-study of Gettysburg is also the harbinger of a new brand of historical method, Geographical Information Systems (GIS), which brings databases about everything from psychology to weather to sound to population, tax quotas, religious networks, economic systems and family histories — into our consideration of historical events and decisions. As Richard White puts it in his introduction to “Placing History:”

The major geographical form – the map – is good at representing some kind of space but not good at tracing relationships through time. The historical form – the narrative – is not very good at expressing spatial relationships. Relationships that jump out when presented in a spatial form … tend to clog a narrative.

Prof. Knowles’ use of GIS is about much more than geography – it about bringing the entire range of new tools in information science to bear on history. New databases can change and amplify the traditional linear narratives of most historical scholarship. As White states, “GIS offers the ability to experiment with different ways of organizing historical data.” This widened lens can give us new ways to interpret the decisions made by people so long ago.

“Of all the ways geography served as the ‘handmaiden of power’ in the nineteenth century,” Knowles begins one of the early sections in her essay, “none as more important than the role of topographical mapping in military campaigns.” She goes on to consider Lee’s own extensive background in the Sioux campaign and the Mexican-American War. She cites Ulysses S. Grant as a leader with “an intuitively brilliant grasp of the lay of the land and an ability to swiftly exploit advantageous conditions.”

The lay of the land would play a key role at Gettysburg. “What McLaws, Longstreet, Warren and Lee actually saw … has received little attention. Scholars have basically accepted the participants’ written statements about what they saw at key moments as recorded in official reports and personal statement.”

Mapping history …showed me how history resides in the landscape.

Knowles finds that there were, in fact, huge gaps in the leaders’ sense of where they were, a “fundamental lack of appreciation by both North and South of terrain intelligence … which lead to strategic blunders and consequently unnecessary deaths” (Gulley and de Vorsey as quoted by Knowles). The oral reports from scouts gave commanders an understanding of terrain which lacked scope. Lee, she concludes, took “approximately seventy-five thousand men into Pennsylvania without [reliable] geological information.” Jeb Stuart did not help, since he failed to send a single dispatch regarding the disposition of Union troops.

Robert E. Lee after the war. (The Civil War Playlist)

What then, Prof. Knowles asks, were Lee’s lines of sight? What was his field of vision? “Can the evidence of sight be used to test the credibility of the generals’ post-hoc justifications, such as Longstreet’s explanation of his long countermarch on July 2?” Her conclusion is that Lee’s decision to press a frontal assault at Gettysburg was flawed:

How could such an exceptional commander, expert in reading terrain, fail to recognize the attack would be a disaster? The traditional explanation, favored in particular by Lee admirers, is that his underling, Gen. James Longstreet, failed to properly execute Lee’s orders and marched his men sideways while Union forces massed to repel a major Confederate assault. “Lee’s wondering, ‘Where is Longstreet and why is he dithering?’” Knowles says.

Her careful translation of contours into a digital representation of the battlefield gives new context to both men’s behavior. The sight lines show Lee couldn’t see what Longstreet was doing. Nor did he have a clear view of Union maneuvers. Longstreet, meanwhile, saw what Lee couldn’t: Union troops massed in clear sight of open terrain he’d been ordered to march across.

Rather than expose his men, Long-street led them on a much longer but more shielded march before launching the planned assault. By the time he did, late on July 2, Union officers—who, as Knowles’ mapping shows, had a much better view of the field from elevated ground—had positioned their troops to fend off the Confederate advance.

From Tony Horwitz, “Looking at the Battle of Gettysburg Through Robert E. Lee’s Eyes,” Smithsonian magazine December 20012

This research helps vindicate Longstreet and demonstrates the difficulties Lee faced in overseeing the battle.

“Good ground” means defensible terrain with a field of vision that minimizes the chances of being surprised by the enemy.

She is careful to call it “an exploratory methodology,” but the potential in a new, data-enriched approach is easy to see. She herself has applied the method to two new subject areas since her essay on Gettysburg. Her newest book, Mastering Iron, uses new methods to take a closer look at the American iron industry. For this project, according to a recent profile of her in Smithsonian magazine, Prof. Knowles first created a detailed database of every ironworks she could find. She then “mapped factors such as distances from canals, rail lines, and deposits of coal and iron ore.” The results? “Patterns and individual stories that emerged ran counter to earlier, much sketchier work on the subject. Most previous interpretations of the iron industry cast it as relatively uniform and primitive, important mainly as a precursor to steel. Knowles found instead that ironworks were tremendously complex and varied, depending on local geology and geography.” Her current project is mapping the Holocaust, in collaboration with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and a team of international scholars. There will be more innovative historical works like hers, and I think we might all benefit from learning how to read the land as she does.

# # #

View the online Smithsonian.com Gettysburg website, which has Bachelder’s changing troop positions and 3D renderings of what Union and Confederate commanders could (and could not) see at six key moments in the battle.

As someone who enjoys the subject of history, this is such a remarkable topic. First of all I did not realize that we could now map previous events. The idea of mapping out the past allows scholars to view history, even more now than ever, with their own methodology. GIS seems to allow such a vivid description of what the layout of war battles were, that it can change how history books may be written, because maybe historians will realize what they may have not before. Based on the land and regions, it seems like just a new viewpoint for historians to calculate the story of history.