West of Everything

THE INNER LIFE OF WESTERNS : Interview with Jane Tompkins

Editor’s Introduction

For a decade or so, I have been looking for a book that could help explain to my students why the Western is such a big deal. Jane Tompkins’ West of Everything is that book.

For a decade or so, I have been looking for a book that could help explain to my students why the Western is such a big deal. Jane Tompkins’ West of Everything is that book.

The Western sets the model for the American hero that we see so much today. Compare the protagonists of films like Robocop, Jack Reacher, Jonah Hex, and even the paranoid fantasy The Bourne Identity and you come up with the same sets of attributes. Stoic, resilient, language-averse, glory-averse, good at fighting of all kinds, attractive to women, the Western hero brings his own moral authority with him. So many of these contemporary heroes are at heart cowboy heroes, searching for their identities and seeking justice in hostile landscapes. To fully understand the modern heroes we watch in all action categories, we must first fully understand The Virginian, Hondo, and Kid Rawhide.

Each generation tells its own version of the Western, from the harsh racial morality of The Searchers to homespun family dramas like the television series Bonanza and The Rifleman to the “Violent West” of Quentin Tarantino’s 2105 film The Hateful Eight and Alejandro Innaritu’s brutal The Revenant (2015). Each story somehow reflects its times. Could Dances With Wolves be made today? In 1941? Yet beneath all of them lies a single structure:

The hero, provoked by insults, first verbal, then physical, resists the urge to retaliate, proving his moral superiority to those who taunt him … The villains, whoever they may be, finally commit an act so atrocious that the hero must retaliate in kind.

It is a special sort of American myth, with an extended set of symbols, structures and conventions that Joseph Campbell could admire.

Jane Tompkins is a most gifted writer. She introduces her ideas effortlessly, as though she were writing a letter to a friend. In West of Everything, we encounter some of the smoothest yet most challenging prose one could hope to find. It is insightful, honest and at times both personal and funny. In a single paragraph, she is able to decode, dislike, and redeem Westerns all at once. Here is a passage along those lines:

Because he must police his body’s boundaries so severely, because he is forbidden to play the baby, because it is better for him to die with his love unspoken than to lose his composure, the pressure the hero feels to dispense with social codes and burst the boundaries all at once is tremendous. One way to do is to get killed …

West of Everything takes apart the component parts of American cowboy stories and sets them on the kitchen table for us to appreciate.

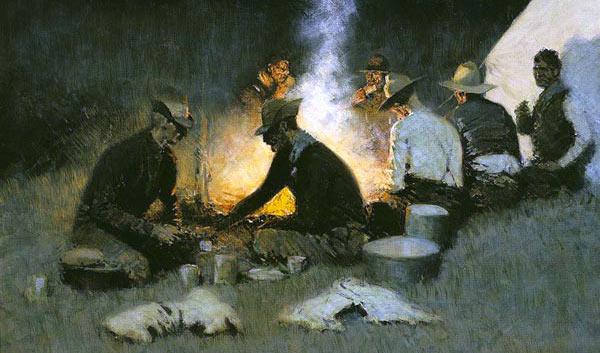

Frederic Remingtons “The Hunters Supper” (1904)

Interview with Jane Tompkins

March, 2016

What three ideas would you like today’s rising generation of students to take away from “West of Everything?”

First, that popular culture is a great place to go to find out who we are. It’s often assumed that only elite or “highbrow” culture has important things to say about the human condition, and it does, but so do movies, popular novels, comics, and TV shows. Popular culture has everything to teach us about the way we’re being shaped by the time and place we were born–psychologically, socially, and spiritually. Because it’s such a well-defined genre, the Western is a good place to place to go to find out about the era that produced it—basically the first 75 years of the 20th century. And relevant, too, since the paradigm it put in place continues to be the model of heroism we have today (Think American Sniper).

The second thing I’d like people to remember is that that model of heroism is—and continues to be—overwhelmingly male. This means that the plot will deal with conflict in the public space—whether it be the open range, a courtroom, Wall Street, outer space, or Middle Earth; the protagonist and the antagonist will both be men, though, occasionally, there’s a woman who has been acculturated to male behavior and ideals, like the female heroine of the Coen brothers’ True Grit or the heroine of Mad Max: Fury Road; and the values being urged on the audience are the solving of problems through domination of the “other,” chiefly through strength, endurance, and physical violence.

The third thing to remember is: this model of male heroism, while it has some positive qualities, is toxic for the hero himself—never mind the people he kills. In a nutshell, it deprives him of joy, pleasure, and intimacy with other living beings—not to mention himself. Bradley Cooper’s role in American Sniper is a great contemporary example. (Because the film was directed by Clint Eastwood, that longtime exemplar of the hard-bitten, anesthetized Western hero. Who knows? He may finally be coming around to recognizing the limitations of this.

Is there a female version of the Western? Is there a corollary to the male wish for self-transformation?

This is a great question because, in order to answer it, one has to recognize that that a female version of the Western is a contradiction in terms. There can be no female version of the Western because what defines the genre, even more than its physical setting, is the character of the hero and the values embodied in his behavior, which are overwhelmingly male. If there is such a thing as a female version of the Western, and it’s the only true revisionary Western I know, it would be Dances with Wolves, in which the hero passes from white to Indian, war-making to lovemaking (“We call you the Busy Bee”), from a nature-destroying culture to a nature-loving culture (hence his name) where he has true friends (“Dances with Wolves, Dances with Wolves, you are my friend forever”), belongs to a community, and leads a happy, domestically focused married life. This is transformation at every level. Of course, a main feature of the movie is a horrible fight between two Indian tribes, but this occurs independently of the main trajectory of the plot.

How would you compare the Western hero to other heroes? Are today’s heroes different versions of Thomas Dunston, or are they essentially different?

As I’ve said, heroes of today’s popular films tend to be extensions of the Western hero. In fact, they exaggerate and even parody the Western hero’s toughness, e.g., Robocop, and it many replications, where the hero’s body becomes part machine. (An interesting inversion of this occurs in Total Recall, where the hero gets his instructions from a baby that lives inside his stomach. An example of the way a film’s unconscious can sometimes show the way ahead). The violence now is twenty times what it was in classic Westerns; maybe that’s why the hero has to be more than human (e.g., The X-Men). The woman, if there is one, is either masculinized or a total bimbo. Rarely do they represent a center of moral authority, as in High Noon.

A different kind of hero does appear in comedy—an anti-Western genre (the Western takes itself seriously), in that the hero is obviously flawed, made fun of, and lacking in a sense of his own importance. These figures—I’m thinking of roles played by actors such as Robin Williams, Owen Wilson, Vince Vaughn, Ben Stiller, Jason Bateman, and Will Smith–are much more positive and hopeful as examples of how to be in this life. They’re vulnerable, they learn from their mistakes, can laugh at themselves, know how to have fun, don’t take themselves too seriously, and are often kind and gentle towards other people.

In the Western, you say that the body and the emotions have no rights, no voice. Has the pendulum swung the other way?

No. At least not in such Westerns as are being made now. (I haven’t seen either The Revenant or The Hateful Eight, but, judging from the trailers, there’s been no change: if anything, things have moved further in the wrong direction). If the question refers to popular culture in general, it’s harder to answer. There’s the trend toward mechanization and prosthesis of various kinds, toward superhuman powers, and martial arts virtuosos–all of which can be interpreted as expressing dissatisfaction with the body, as such. But not much that shows the body as a site of pleasure, wisdom, comfort, or communication.

Are Native Americans any more present in our narratives today than they were in the mid-and-late 20th century?

I would say less so. I can’t remember the last time I saw a movie or a TV series that focused on Native Americans. The last time I saw a Native American on TV was in an animated ad featuring Sacajawea.

# # #

Book Review “West of Everything”

Still from The Hateful Eight (2015) : credit the Weinstein Co.

One of the reasons I find Jane Tompkins’ West of Everything so compelling is that it is gives students a clear path to understanding all of their favorite hero stories. The most popular lesson plan in my composition class is on heroes – our students have seen and read thousands of hours of hero/heroine stories, and they will certainly listen to breakdowns of their favorite characters and what they might represent.

Professor Tompkins refers to a School of Virility that began with Jack London and the gunslingers – our present coming-of-age generation is consuming endless iterations of this same heroic model. Its lineage traces directly to Hemingway to Sam Spade to The Punisher, who speaks rarely, outdraws his enemies, and retreats to nature to nurse his wounds. Many of Tompkins’ insights apply equally to today’s post-Western protagonists.

A second reason to read West of Everything is that the author’s writing is so natural and so rewarding. Almost every page delivers an original insight. For example:

One has to ask why … a genre should arise in which death of a particular kind should command so much attention. We tend to act as if there had always been stories about men who shoot each other down in the dusty main street of desert towns. But these stories came into being only shortly after the towns themselves did and, thought the shooting stopped a few years later, American culture has been obsessed by that particular scene of violence ever since.

Language constitutes and inferior kind of reality, and the farther one stays away from it the better.

Elsewhere she writes this: “Fear of losing his identity drives a man west, where the harsh conditions of life force his manhood into being.” This is perhaps as close as we find to the central thesis or narrative line of her book. It leads her to a consideration of “the extent to which the Western is involved with pain.” The close descriptions of the cowboy hero’s tribulations earn him (and the reader) the right to exact revenge. “In the intrapsychic politics the Western sets up, the body and the emotions have no “rights,” as it were, no voice; like the animals, they do not speak.” But they do get their day – at the story’s climax, there is the ritual duel with evil:

What justifies his violence is that he is in the right, which is to say that he has been unduly victimized and can now be permitted to things which a short while ago only villains did … The structure of this sequence reproduces itself in a thousand Western novels and movies. Its pattern never varies.

One of Prof. Tompkins’ most telling ideas has to do with cattle. “The invisibility of cattle,” shed writes, “in Westerns – the invisibility, that is, of their terrible suffering at human hands – and the celebration of the hero’s pain are intricately linked.” She goes on to build a larger theory:

The cattle are the film’s unconscious. They surround the characters, often dominate the screen, pervade the atmosphere with the quiet, massive strength of their bodies, the slow, throbbing presence of their lives. Yet in some profound way they are totally unnoticed.

Later in the book, in a section devoted to a close study of Ford’s Red River, one of the author’s touchstone works, she delineates all who benefit from the relentlessness of the film’s hero, Dunson, who conquers raging rivers, well-meaning friends, rebellious cowhands, greedy Mexicans, savage Indians, and clinging women to deliver his herd:

They are all means to an end, the realization of his purpose. The movie criticizes his persistence but ultimately sees it as heroic. Everyone benefits from it in the end. The ranchers make a profit, the hands get paid, the town of Abilene and the railroad are in business. Matt inherits half the ranch, Tess gets Matt, and Dunson gets to be a hero. Everyone is better off than they were before – everyone, that is, but the cattle. They get to be herded onto boxcars and taken to the slaughterhouse to Chicago.

Another idea pops up early in West of Everything, the idea that Westerns celebrate work. It is not by accident, she argues, that authors like Louis L’Amour place their heroes in situations requiring hard work to conquer, or as the author puts it:

Hard work is transformed here from the necessity one wants to escape into the most desirable of human endeavors: action that totally saturates the present moment, totally absorbs the body and mind, and directs one’s life to the service an unquestioned goal … Rather than offering an alternative to work, the novels of Louis L’Amour make work their subject.

According to Tompkins, the Western says no to language and yes to landscape. Language is depicted as a sort of trick, a device to fool and honest man.

The Western’s attack on language is wholesale and unrelenting … Language constitutes and inferior kind of reality, and the farther one stays away from it the better.

Because the genre is in revolt against a Victorian culture where the ability to manipulate language confers power, the Western equates power with “not-language.” And not-language it equates with being male.

What language we can find in westerns like L’Amour’s 1954 novella Kilkenny or John Ford’s 1956 film The Searchers (or, for that matter the 2004 action film and transplanted Western The Punisher) Tompkins describes as “abstract.” I take this to mean that the short and enigmatic sentences which the Western heroes give out neither describe nor connect to what is actually happening in the story, but veer off into a higher dimension, making some other kind of sense. I cannot re-read the Sackett stories or watch Paul Newman in Hombre without thinking of this.

And so men imitate the land in Westerns; they try to look as much like nature as possible.

Silent and stoic, the landscapes of Colorado and Wyoming act as a sot of tonic or offset to the evils of words.

At this point, we come upon the intersection between the Western’s rejection of language and its emphasis on landscape… The interaction between hero and landscape lies at the genre’s center, overshadowed in the popular image of the Western by the gunfights and chases … In the end, the land is everything to the hero; it is both the destination and the way.

Elsewhere, she clarifies this connection between hero and landscape in stories like First Blood and Rambo as well as The Lone Ranger:

And so men imitate the land in Westerns; they try to look as much like nature as possible … The qualities needed to survive on the land are the qualities the land itself possesses – bleakness, mercilessness. And they are regarded not only as necessary to survival but as the acme of moral perfection.

The structures and values and tropes of the Western dominate much of modern American storytelling – including so many of the heroes our students currently watch and read. West of Everything shows us how and why.

Marvel Comic’s The Punisher an action hero with clear Wesern roots

This article is insightful into the everyday heroism and tales in popular culture we find so fascinating. It forces the reader to reevaluate their opinions on this genre, as well as question the importance of these gallant characters we idolize.

Manuscript is a collective name for texts

only a few survived.

and 12 thousand Georgian manuscripts

XVII century was Nicholas Jarry [fr].

number of surviving European

written on the parchment was scratched out

A handwritten book is a book

ancient and medieval Latin,

secular brotherhoods of scribes.

from a printed book, reproduction

bride, Julie d’Angenne.