War, Society, and Commerce in World War II

From Submarines to Suburbs: Selling a Better America, 1939–1959 by Cynthia L. Henthorn

Illustration commissioned by JES copyright @ 2011 Margaret Hurst

Editor’s Introduction

The success of most wars depends in part on several important non-combat factors, and crucial among them is public support.

In her fascinating and ambitious 2006 book, From Submarines to Suburbs, Cynthia Henthorn examines both the relationship of commerce to war and the relationship of the citizen to war. It is a timely topic, since America is currently engaged in two wars under very different conditions than World War II. There is no corollary today to the “arsenal of democracy” that so successfully powered America’s World War II efforts, and the American public seems relatively disengaged from today’s wars. In the following interview, Henthorn introduces readers to her topic, discussing the subtle and not-so-subtle connections between our kitchens, our concept of the future, our corporations, and World War II. A book review touching on some of the main points of her book follows.

Interview with Cynthia L. Henthorn, Ph.D

07/2011

Can you explain America’s “arsenal of democracy?”

The phase, “arsenal of democracy,” comes from a speech made by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in late 1940. Roosevelt was referring to America and its manufacturing strength. From this manufacturing strength, Roosevelt declared, America would be able to equip the allies in the fight against Nazi Germany and the Axis powers.

To get a sense of the real impact of this phrase and its meaning, one needs to look at it in the context of the times. In late 1940, America was still in the grip of the Great Depression and had been for about 10 years. Moreover, America had not yet been pulled into the European or Pacific conflicts. This speech pre-dates Pearl Harbor by about a year. Why should Americans bother about a war overseas? Many Americans rejected the notion of getting involved in another World War, ostensibly fighting other countries’ battles at America’s expense.

From the vantage point of many Americans at this time, the country’s manufacturing was weak. If American manufacturing and business had failed to pull the country out of the Great Depression, how was it supposed to equip the allies to win a war against Germany and Japan, who had been manufacturing for war throughout the 1930s? Roosevelt’s phrase, “the arsenal of democracy,” was a means to build Americans’ confidence in their country, business, manufacturing, and especially, themselves.

Americans born after World War II may not realize just how huge and how varied this “arsenal” was. Can you give them an overview, or context, of what America manufactured during the war years?

Every component of life in America during World War II revolved around channeling resources toward the war effort. This meant that food (like meat and sugar) and supplies (such as tires, gasoline, women’s stockings) were rationed so that such resources could go toward supporting military personnel and building the weapons and equipment the military needed for fighting a war. Manufacturers of every conceivable consumer product, from lip stick cases to washing machines, stopped production of items for the American public to buy and turned their facilities into assembly lines that churned out guns, parachutes, tanks, planes, etc.

The “arsenal” also referred to people power. Women were encouraged to take jobs that had been traditionally the domain of men and from which women had been barred. Many of these jobs were in factories.

Roosevelt’s phrase, “arsenal of democracy,” was meant to imply an inclusiveness of all Americans, no matter their race, creed, ethnicity, or class. During the war, African Americans leveraged wartime imperatives, such as the fight for democracy and freedom, to make social, political, and economic gains for people of color who had largely been denied full participation in American democracy.

From a color article in December 1937’s Popular Mechanics.

What is “the arsenal of domesticity,” and why would this become so crucial to the American war effort?

The phrase is one I coined to capture the essence behind Roosevelt’s “arsenal of democracy.” During the war years, many advertisements and official war information messages did not simply explain how America could win the war, but voiced such messages through the language of consumerism. This language drew from an ideology that stressed how every-day objects found in the most mundane and routine areas of American life could be harnessed to win the war. Such products were often identified with the home, housework, and women. Hence, the domain of domesticity was often talked about as a veritable stockpile of untapped resources that could easily be transformed into military supplies and a subsequent allied victory.

The “arsenal of domesticity” also refers to the way in which women were recruited for war work, especially in factories whose assembly lines had been converted from consumer to war production. Much recruitment literature of the time stressed how domestic chores and skills associated with “women’s work” could easily be transferred to factory work, the traditional domain of men.

How would you characterize the American attitude towards business before the war?

Industrial management’s reputation among both blue- and white-collar classes had soured as a result of the 1929 stock market crash. The sentiment at the time was if business and capitalism had failed to reverse a decade of economic depression, how was it going to muster the strength to win a war on two fronts (i.e., the European and Pacific theaters)? Many wartime messages found in advertising sought to rebuild Americans’ confidence in business – especially big business – and capitalism during the war years.

What was the idea of modernity as it applied to the U.S. household? How did that idea develop and serve to motivate the American populace?

“Modernity,” as it applied to the American household, referred to comforts and conveniences created as a result of labor-saving designs and devices.

There are many ways in which the “modern” household was leveraged for wartime propaganda messages and its values articulated by business or the Roosevelt administration. One example would be the “arsenal of democracy” concept, discussed earlier. Another would be how business created visions of a postwar future where every American would benefit from a “modern” standard of living. The comforts and conveniences of this modern standard of living would be affordable to everyone, so the messaging went, because American businesses, assembly-lines, and manufacturing resources had undergone a magical transformation during the war.

As a result of this alchemical transformation, a higher standard of living, replete with labor-saving machines, would be available (ostensibly) to all Americans once victory was achieved. The idea of a “better America,” born of wartime manufacturing was a strategy employed by business AND Roosevelt’s New Deal administration to motivate the public’s enthusiastic participation in the sacrifices needed for the war effort.

How did this idea of progress and technology impact different factions within American society?

It was more like different factions leveraged popular conceptions of progress and technology at the time to further their own agendas.

For example, as a result of manufacturing’s conversion to produce for war, a higher standard of living, replete with labor-saving machines, would be available to all Americans after victory. According to advertising and marketing messages of the time, the war acted as a magical crucible that revitalized American manufacturing, transforming the economic “illness” of the Great Depression into a robust and healthy super-machine that would churn out every conceivable modern convenience at an affordable price.

In this respect, business set itself up as the hero of the war, not only in terms of beating the Axis powers, but defeating economic depression. Taking credit for victory (on the battlefield and on the economic home front) was a deliberate marketing strategy undertaken by business during the war as a means to undermine the popularity of the New Deal administration.

Conversely, African American journalists and commentators during the war were in the minority in their critique of business and government messages promising a “better America” after victory. The African American community leveraged such messages as a way to spotlight the inherent paradox of American democracy. Messages about black progress focused on gaining equality through economic emancipation rather than on dreams of an effortless postwar future.

Can you explain the ideas of mobilization and reconversion?

Mobilization means preparing, or converting, civilian production and resources for the purposes of war. While reconversion refers to changing production and resources back to their former pre-war, civilian purposes. In the context of wartime advertising, reconversion also meant planning for a better America after the war.

How did the ideas of “The House of Tomorrow” and “A Better America” play out after the war?

The reality of the postwar years surfaced in stark contrast to the wartime messages forecasting how modern comforts and conveniences would revolutionize a “better America.”

Even though the mythic “better America” did not magically appear as soon as the Axis powers surrendered, advertising messages persistently claimed that it had. It’s possible that advertisers continued disseminating the same themes of a “better America” after the war to stimulate postwar prosperity by encouraging consumer confidence and hence spending. The reality was that many manufacturers returned to producing prewar models of consumer goods rather than miraculous products that were destined to revolutionize American living.

Perhaps mass-produced housing developments exemplify the way in which the war influenced a “better America” – at least for some Americans. One could argue that postwar Levittown houses, and similar assembly-line suburban developments, democratized home ownership for the white working class. Levittown houses built on and continued a trend established during the Depression years of resolving social inequities through affordable access to single-family houses.

When housing for military personnel and war workers demanded an assembly-line approach to constructing shelter, the war provided architects, builders, and manufacturers with an opportunity to develop techniques, materials, and processes that would generate housing for the masses at an unprecedented rate. During the war years, news of this form of assembly-line house construction was extolled as the long-awaited means toward democratizing middle-class home ownership. Since the “better America” messages inferred that the war would open a wider path to middle-class standards of living, it is arguable that relatively low-cost tract housing, like the Levitts’, exemplified one way in which the “better America” predictions came true.

Following the Allied victory, realities of the cold war influenced American concepts about progress and the political meaning of “a better America” — more so than Levittown-like houses. During the 1950s, many advertisements and commercial messages claimed that progress for the American household advanced along with cold war military science and technology. Many postwar advertisers with defense contracts asserted that domesticity had been further revolutionized by defense-related technologies. A permanent cycle of mobilization and reconversion defined the postwar American economy and its new identity as a global power. Champions of free enterprise justified greater and greater military expenditures as necessary for economic growth and spreading the gospel of democracy. Similar to the ways that the fight to save democracy had been articulated in World War II, the postwar version of this mission was expressed in the language of consumerism. By the time Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had their infamous “kitchen debate” in 1959, packaging democracy, defense, and consumerism together as the necessary ingredients for modern progress had become the norm.

Where are we today in terms of these two powerful ideas? Are we still dealing with their legacies? Are there similar connections between wartime success and domestic progress being made in today’s wars and today’s society?

Definitely. Our world today is the child of the path that business carved out in the years following World War II. Despite the social, economic, and technological changes that make today’s world so vastly different from the World War II and postwar eras, certain undercurrents remain. America’s national economy is heavily dependent on defense- and security-related expenditures. War, national security, and private corporate security are big businesses in today’s ubiquitous wars, especially the assault on terrorism and the “war on drugs.” And despite global environmental crises, the lust for labor-saving technologies prioritizes our pursuit of “progress” above other concerns and ironically drives consumers to perpetually strive for building a “better self” through what we can buy, rather than building a truly “better America.” Commercial messages bombard us today with the idea that science and technological progress have put us in control of our destiny. Yet in the scramble for an increasingly effortless lifestyle, in the insatiable quest for a “better self,” we have lost sight of just how much of our control we have lost as a result of “progress.”

B-24 Liberators under construction at Ford’s Willow Run line during World War II.

Cynthia Lee Henthorn holds a Ph.D. in art history from the City University of New York. She has taught design history, with an emphasis on advertising and marketing trends, at art and design colleges in New York City. In her current role as a developmental editor of online courseware, she creates interactive, Web-based textbooks and assessment tools for the higher education market.

Book Review

From Submarines to Suburbs: Selling a Better America 1939-1959 by Cynthia Lee Henthorn Ohio University Press (2006)

By Tom Durwood

Does war just happen? Do armed hostilities break out simply because a handful of leaders cannot resolve their differences, or are there deep connections between the wars that we fight and our societies?

Professor Cynthia L. Henthorn takes on these and other important questions in her book From Submarines to Suburbs: The Selling of a Better America 1939-1959. Her specific reference is World War II and the idea of modern homes, but we can take many lessons from her thoughtful account and apply them to our present circumstance.

She undertakes to tell the home front war for mobilization in all its complexity. She includes topics such as mobilization through symbol management, the positioning of wartime types in narratives of mobilization, hygienic solutions for the House of Tomorrow, and the corporate “Campaign to Save the American Way.” At the end of the third section, she details how the symbols of the mobilization campaign carried forward into the Cold War, linking it to Victor Gruen (who sold the early shopping centers as effective bomb shelters) and the age of the shopping mall (which seems to linger on, against all odds).

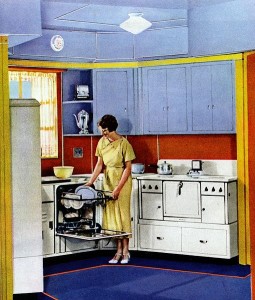

It is a big story to tell. Henthorn focuses her investigation at the starting point of advertisements. She includes over forty ads in the book from the World War II era and works backwards, analyzing the commercial structures and social realities beneath them. Ads depicted a labor-saving world of tomorrow featuring miracle houses that would clean dishes automatically. Here is the text in an ad for Norge Refrigerators that is typical of the day, with a visual depicting a housewife surprised to see a tank in her kitchen:

Startling, isn’t it? Here is the new 1943 Norge Rollator Refrigerator which you are doing without … Your reward for doing without your new Norge is the knowledge that you, too, have helped to speed the day of Victory and Peace. When the guns are stilled, you can be sure that Norge thinking and Norge skill, stimulated by the stern school of war, will bring you even greater satisfaction, greater convenience than you have enjoyed before.

The advertisement’s explicit promise is that our sacrifices to the war effort would directly produce the perfect home after the war – modern, ordered, sanitized, mechanized. In these mobilization narratives, writes Henthorn, “the streamlined kitchen maintained the health of the perfect body, the perfect class, the ideal citizen, the consummate homemaker.” These “world of tomorrow” narratives proposed to American civilians the following tradeoff: work and sacrifice now, invest in war-time bonds, and enjoy new kitchens and prosperous futures after the war.

Professor Henthorn structures her exposition in three sections: Mobilization; Postwar Planning; and Postwar Progress, with an Afterword on the “Better America” today. As the author explains, “The details of World War II mobilization are a fascinating dramatic mix of struggle, failure and triumph. The focus of Part I is not this history, however, but the glorified picture of mobilization … what psychological obstacles were faced and how they were overcome forms the subject of the next three chapters.”

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was not subtle in connecting battlefield victory to domestic concerns. In this passage, Prof. Henthorn recounts FDR’s enlistment of manufacturing in the war effort:

America’s “arsenal of democracy” relied heavily on making an arsenal out of domesticity. In his speech delivered late in 1940, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt described how Machine Age progress would evolve into democracy’s winning weapon against fascism. Manufacturers of every device from wristwatches to locomotives, he declared, were churning

out new lines of goods to equip America’s allies for war. From domestic commodities as unwarlike as “sewing machines and lawn mowers” would emerge “the implements of defense.”

“New and improved technologies in the hands of a ‘socially responsible’ corporate America were advertised as the key to democratizing progress,” she writes. “Hence, the forecast technological revolution was not simply a domestic one, but a social one as well.”

One key rivalry she runs across is the opposition between the New Deal and the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). The corporate members of NAM deeply mistrusted the economic controls from the New Deal as threatening to free-market capitalism. The book “uncovers an ideological debate that reveals big business’s motives behind wartime narratives of progress.” The mobilization stories embedded in advertisements cleaved closely to official government policy.

Once World War II was over, the dynamics of this powerful symbolism did not stop. American political policies and national interests merged with our corporate promises. To that point, Henthorn quotes the following exchange from the “kitchen debates” of the Cold War period:

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev: “In another seven years we will be on the same level as America … In passing you by, we shall wave. If you want capitalism you can live that way. We feel sorry for you.”

Vice President Richard M. Nixon: “You may be ahead of us … in the thrust of your rockets … We may be ahead … in our color television.”

Khrushchev: “No, we are up with you on this too.”

Nixon (pointing to a panel-controlled washing machine): “In America, these are designed to make things easier for our women.”

Khrushchev: “A capitalist attitude … Newly built Russian houses have all this equipment right now. In America, if you don’t have a dollar you have the right to [sleep] on the pavement.”

Nixon (showing the Russian a model American house): “We hope to show our diversity and our right to choose … Would it not be better to compete in the relative merits of washing machines than in the strength of rockets?”

Khrushchev: “Yes, that’s the kind of competition we want. But your generals say: Let’s compete in rockets.”

Henthorn’s book is a valuable reminder of the commercial and sociological aspects to war. The author brings many analytic weapons to bear on her topic, not least among them her background in both design and marketing. Her valuable book demonstrates that understanding armed conflicts involves much more than military history.

POSTSECONDARY LEVEL

L E S S O N P L A N T O A C C O M P A N Y

“From Submarines to Suburbs: Selling a Better America 1939-1959”

JOURNAL OF EMPIRE STUDIES WINTER 2012

1. What is the author’s thesis?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

2. What was “the mobilization effort”? Was that important to the outcome of the war?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

3. How do you compare the war effort then to the war effort behind our engagements in Iran and Afghanistan? What accounts for the differences?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

4. According to the author, corporations were able to successfully link the benefits of the war effort to the American family? Is the public involved today in the same way? Here are two different views:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/08/19/AR2009081903066.html

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

5. How is the American home thought of today, compared to the “home of the future” depicted in previous decades?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

6. Who ultimately won the war of words between Nixon and Khrushchev? Were rockets or washing machines the decisive factor?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

7. The author describes a rivalry or opposition between the New Deal and American companies. Does that same rivalry exist today? Do corporations mistrust government spending?

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1945357,00.html

http://www.newstatesman.com/economy/2010/09/survey-found-governments

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

I think that it is extremely remarkable how much emphasis was put on the support of war from the homeland during World War II and the effect it has had on our society today. The one thing I wish we could do in todays society is have the same kind of camaraderie in our nation today with regards to the war as we did back then.

This article made several great points. The way that the US was able to motivate the citizens and unite a country for one cause was amazing, it almost seems like it would be impossible to do what they did in current times. Another interesting point that was mentioned was that the US in a way used the war to build confidence in American industry. Because of the great depression many people lost faith in the production abilities of our industry compared to Japan and Germany. In addition to that the war made producing goods more efficient from houses to spoons everything was being made at a faster pace.

Bouncing off of Cadets Picco and Kangs comments, the one thing that was present in the generation of those who fought in WWII was the will to fight. Everyone was waiting in line to join up with the Army, the Navy, and the Marines.

In the present day only 1% of our population has the will to serve in America’s armed forces. Our nation has lost the will to defend itself. The one thing I am glad to see is that even though a lot of citizens do not support our current wars, they still support our troops overseas like citizens did during WWII.

This article gave insight on how life during World War II was. Because I was born well after World War II I didn’t really know too much about the life of the citizens during the war because that was never anything taught in school. To know that the people back home were doing all that they could to help support America during this war makes me feel a sense of pride for my country. The whole country literally dropped what they were doing to help out the troops. For manufacturers to halt their line of work to help build war supplies boggles my mind. All of this support helped build up confidence in our own country following the lingering effects of The Great Depression. Who knows maybe if we would have done as much as they did back then then maybe the war going on now would have ended sooner.

This article provided a thorough outlook on what America was like during the war. It explains the everyday sacrifices people made to provide for the soldiers fighting a war across seas that initially never had anything to do with the United States. The community backing for the war provided the soldiers with the motivation to continue to fight. Would that help the Soldiers today? Everybody has their own opinion on who’s war we are fighting today but when it comes down to it we need to provided support of the men and women fighting the war. Give those soldiers the same support the Americans did during WW2. I was very surprised of how the war benefited the United States industry, since it just came out of the Great Depression. The war provided a means for many businesses to resurface in support for the war. Furthermore the birth of women obtaining jobs that men usually held to support the war effort helped pave the way to further women’s rights and the use of African Americans in the war provide a equal fight field regardless of your color.

This article made a key point that the support of the American public has a directly proportional impact on the success of the military, specifically in World War II for this article. If you look throughout history at the wars that America has been in , the morale of the soldiers is increased the more the people back home show support. I believe that this concept still applies to America during Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan.

It seems as though back then the country was more united than it could ever be today. Even though there was a lot of trouble back then among the different groups, I feel like when it came down to it, the American people put their differences aside and got it together.

This article shows that they had what it takes to end what was going on back then. Why can’t we learn from this and stop the troubles today?

The “Arsenal of Democracy” that was, is no longer, as evidenced through a larger population of people voting against going to war. In fairness, look at the 10 years preceding the start of WWII. They were the worst 10 years this country has ever seen economically. The government was out of ideas in getting the economy out from the dumps, 1 in 3 people were unemployed, and there was no sign of growth anywhere. As soon as the war became a possibility, the government capitalized on it and used it as a way to get the economy growing. People were desparate. Today, with our economy in recession, if the government tried to use a potential war as fuel to bring the economy back up and growing, it would backfire horribly. We are far more technologically advanced than we were in the early 40s. People are no longer assembling guns, machines are. The majority of military goods are produced by machines. So we can replace a far more efficient machine with a less efficient human and take a hit on our level of efficiency, or we can not use people in our manufacturing plant, and maintain our efficiency and lose a job. Tactics used in the 40s no longer are useful today.

Editor’s Corner

1. Yes this editor is the most brilliant man in the Western Hemisphere, because this man not only going to make their lives better but make a huge impact in their lives. This man has a power no other human has, is the power to make humans a better writer. Of course he is smarter than Albert Einstein! Albert never taught at Valley Forge? Did he? This man is smarter than Albert Einstein because this man’s lessons can make a young student brilliant.

2. Yes, this man deserves an award of being the best teacher here at Valley Forge, no scratch that, THE WHOLE WORLD Mr. Durwood! You’re the best English teacher I ever had!

Editor’s Corner

1. Yes this editor is the most brilliant man in the Western Hemisphere, because this man not only going to make their lives better but make a huge impact in their lives. This man has a power no other human has, is the power to make humans a better writer. Of course he is smarter than Albert Einstein! Albert never taught at Valley Forge? Did he? This man is smarter than Albert Einstein because this man’s lessons can make a young student brilliant.

2. Yes, this man deserves an award of being the best teacher here at Valley Forge, no scratch that, THE WHOLE WORLD Mr. Durwood! You’re the best English teacher I ever had!