Visigothic Architecture

ARCHITECTURE CROSSING CULTURES

Some Observations on Visigothic Architecture and Its Influence on the British Isles

By Jamie L. Higgs

How did Visigoth churches get to Ireland from Iberia?

— Architecture, Religion, Iberian Studies

— Introduction, Interview, Excerpt, Lesson Plan, Full dissertation

Introduction

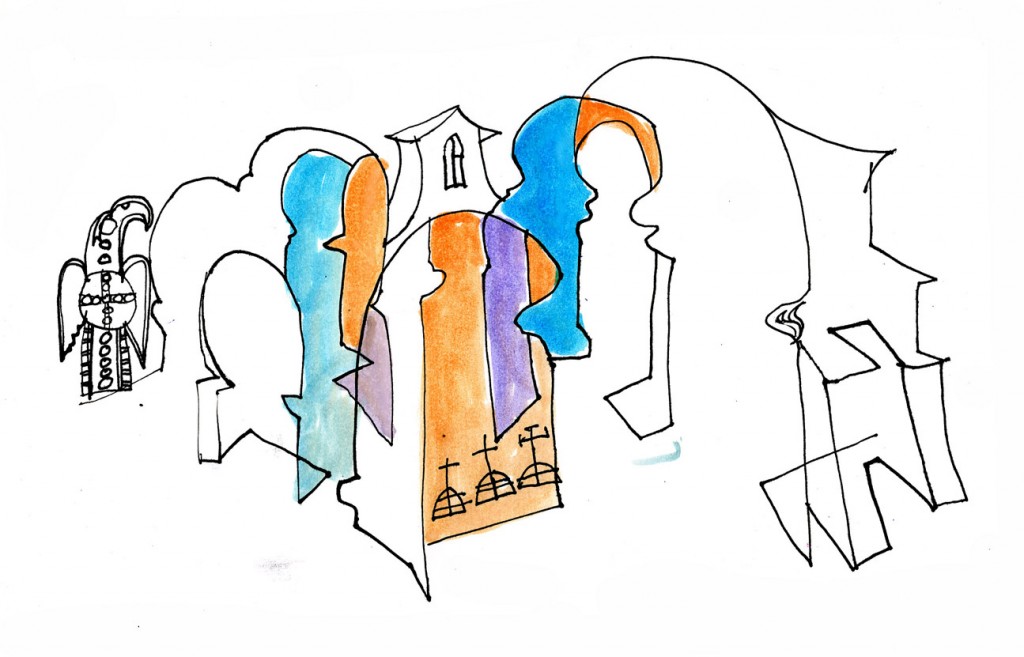

How do cultural influences travel from place to place? It is sometimes easy to trace these lines of influence in the modern era, but how did this process work in the past? Looking at the past, how can we decipher which elements of architecture or music or literature came from which sub-culture? In her dissertation, the author looks closely at churches of the 9th century and finds that the architectural styles we have thought of as Anglo Saxon may actually be Visigoth. She cites a tiny Celtic colony called Britonia, located in the Galician region of what is nowSpain, as a vehicle or agent for the transmission of Visigoth architecture toEngland.

The connections among these far-flung church structures indicate that, while it is easier for us to consider “English” history and “Spanish” history as separate, it was in some ways a single interconnected medieval world.

Elsewhere in the dissertation, the author points out that for many centuries in many cultures, “architecture” meant principally church architecture. You and I may take it for granted that all ancient churches are designed in more or less the same layout, but Prof. Higgs lays out a timeline of progression for each element of church architecture — It is also interesting how the content of the church service influenced the church’s design. As often happens, you cannot fully appreciate a single field of study without understanding several others – in this case, the spread of Christianity is linked with the spread of architecture.

The Iberian peninsula is a term for what we now call Spain and Portugal.

Like all dissertations, this is written primarily for other scholars, so general readers like you and me have to slow down to sift through the scholarly references. All the footnotes have been removed from this excerpt and are available in the full dissertation (which is available in a file right next to this one). Also keep in mind that this excerpt takes passages from different sections of the dissertation. We are rewarded with Jamie Higgs’ view into a medieval world which, like ours, may have been unusually interconnected.

Interview with Jamie L. Higgs 07/2011

Who are the Visigoths? What were they like?

The history of the Goths begins centuries before the Visigoths are identifiable as a separate group. During the first century C.E., they are part of the Wielbark and Cernjachov cultures which originates in Pomerania and the lands on the shores of theBaltic Seato either side of the lower Vistula River. In the second and third centuries the Tervingi and Greuthungi Goths, among others, emigrate southward. During the third century, these groups settle in the area of theBlack Sea, between the Don andDanube. They are known as raiders. By 250, the Goths become major players in the eastern and northern hinterlands of the Carpathians and theBlack Sea region.

In 251, the Goths defeat the Romans inMoesia. For eighteen years, they raid and plunder theBalkan PeninsulaandAsia Minor, attacking Athens,Ephesus, Pityus, Trapezus, Pontus, Bithynia, Propontis, Chalcedon, Nicomedia, Nicaea, Apamea, and Prusa. Later, in 270, they attack Anchialus and Nicopolis, and, because of their growing power, Emperor Aurelian concedes Daciato them. During this period, the Gepids, a Germanic tribe from the southern Baltic region, drive a wedge between the Tervingi branch of the Goths, west of the Dneister, and the Greuthungi, east of the Sea of Azov.

By the fourth century, the dominion of the Tervingi Goths, known to the Romans as the Visigoths, extends from theDanubeto the Don. At its fullest extent it spreads over a broad belt of territory running east from the Carpathian Mountainsto the riversDnieperin the south and Donetz in the north. By this period, the Visigoths are part of the Roman imperial system.

The Visigoths are converted to Arianism during the fourth century by Ulfilas (311-383), who becomes the apostle to the Goths. Because Arianism is denounced by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I in 381, this conversion puts the Visigoths doctrinally at odds with their numerous Roman subjects in the centuries to follow. In 375, the Visigoths move south of the DanubeRiverand into the Roman Empireand settled in Moesia. In 401 they are led into Italyby their king Alaric I (395-410), and they sack Romein 408, 409, and in 410. They are allowed to settle in southwestern Gaul (Arlesand Narbonne) as federates, military allies of the Empire.

Where and when did they rule?

The Visigoths begin to cooperate militarily with the Romans inSpainaround 416 in order to rid the area of the Vandals. As a result, by 418, the Visigoths are given lands in the Geronne Valley between Toulouse and Bordeaux; in 419 they are given the area ofAquitaine. In 475 King Euric (466-484) declares his independence fromRomeand expands his kingdom eastwards to theRhoneand southwards to the Mediterraneanand the Pyrenees. By the end of the century, the Visigoths cross the mountains into Spain and many of them begin to live in the Spanish provinces. They eventually win control of the entire peninsula apart from the kingdom of the Suevi inGaliciaand the formidable mountain territory of the Basques north of Pamplona. Euric’s son Alaric II (484-507) rules over the largest political unit inWestern Europe. Apart fromGaliciaand the Basque mountains, his peaceful and orderly kingdom stretches unbroken from the south bank of the Loireto the Pillars of Hercules. Throughout his reign, however, the Franks of Gaul become increasingly threatening. In 507, Alaric II and the bulk of his army are destroyed byClovisat Vouillé, nearPoitiers. The Visigoths lose most of their Gallic possessions and, henceforth, apart from the province of Narbonensis, they are confined to four provinces of Spain—Tarraconensis, Carthaginiensis, Lusitania, and Baetica.

What was distinctive about their architecture? What were other churches throughout Europe like?

Visigothic-period architecture utilized space compartmentalization and architectural barriers creating a sense of mystery with its alternation of light and dark pockets. Generally, other sixth and seventh century churches throughout Europe, namely inRome, were open in their space planning considerations.

How did their architecture get to England?

Visigothic-period architecture per se is not found inEngland. That said, planning considerations of Visigothic-period churches, like space compartmentalization and architectural barriers, are observable in Anglo-Saxon period buildings. In rare cases, both north and south, this preoccupation with architectural barriers resulted in the construction of full walls separating the eastern and western ends of the churches. I contend that these commensurate space planning features are the result of similar liturgical needs. The church of Spain during the Visigothic period practiced the Mozarabic rite while many communities in England continued to maintain the Celtic rite. These rites are more similar to each other than to the contemporary Roman rite and may have required similar architectural space usage.

Where can we see this Visigothic influence?

We can see the influence of Visigothic-period architectural considerations in the use of complicated subdivisions, chancel barriers and even full-walls that were all in evidence to varying degrees in Anglo-Saxon period constructions.

Why is this significant?

Visigothic Spaincan be counted among the ecclesiastical and architectural influences working in Anglo-Saxon Britain. Ideas from the south could have been indirectly transferred by way of the same routes that Iberian texts travel to the North, through the general comings and goings of traders and ecclesiastics. All of this suggests thatIberiawas not an isolated enclave that much scholarship of the past has proposed. Rather, it is the case that this geographical region and its respective culture was functioning as part of a much wider and interconnected early Medieval world.

What other cultural influences traveled from Iberia to Britain?

Connections can be shown to exist betweenSpainand the British Isles from as early as prehistoric times; the two regions are connected by Atlantic trade routes. Very early physical evidence for contacts between Iberia and the North includes two groups of megalithic building types, known today as Passage Graves, dating from 2500 B.C.E.—one in the southern and southeastern Spain, the other continuing this group northwards through Portugal. From this western Mediterranean center one primary sea-borne movement brings the earliest types of passage graves to certain points on the coasts of France, Britain, Ireland, and possibly eventually to northern Europe. Among other artifacts, a small bronze figurine with Iberian affinities from an Iron Age site (Period A, 500-200 B.C.E.) in Co. Sligo, Ireland indicates that the southern part of the Atlantic trade route is still open at this period.

Paulus Orosius, in his Seven Books of History, describes some localities in Spain: “There in Galaetia is situated the city ofBrigantia which raises its towering lighthouse, one of the few notable structures of the world, toward the watchtower of Britain.” Orosius is probably a native ofBraga, the ancient Bracara, some distance to the south of the later British church foundation of Britonia. His words, written about 418, testify to a traditional awareness in Galicia of Britain as a neighbor over the water. Surely, those inBritain are likewise aware of Iberia. Because the seaways connectingBritain,Ireland, andSpain are frequented from prehistoric times, a migration to Spain of Britons in distress later in the sixth century is not surprising.

As it were, some time during the sixth century, a number of people from Britain (estimates range from hundreds to perhaps tens of thousands) establish a colony in Galiciacalled Britonia. Gildas, in his work De excidio britanniae, describes how the British Celts, who occupy almost all of Britain at the beginning of the fifth century, in response to attacks by the Irish, Picts, and Anglo-Saxons, “make for lands beyond the sea” including northern Spain. The Britons occupy an area of land stretching presumably from the neighborhood of Mondoñedo northwards to the sea and also extending across the River Eo toAsturias, where they have a few churches. This area is an extensive tract of land, and its size suggests that it is no mere handful of Britons who land inSpain.

While the Celtic origin of Britonia is certain, we cannot be certain of the date of its foundation or to the identity of Mailoc, its earliest recorded bishop, who signs the acts of the Second Synod of Braga (572). It seems probable that Mailoc is at once bishop and abbot of a monastery, perhaps Santa María de Bretoña.

Spanish church councils include a number of canons that could be transmitted by way of ties betweenSpain andBritain, thus influencing the developing church ofBritain. A detailed review of the attendees at these councils and the canons produced reveals the important liturgical practices of the day which could be disseminated. Furthermore, such councils present points of interest which demonstrate that influences from the North, like the style of tonsure and the date of Easter, do indeed exist inSpain and it is improbable that such influences are only one way.

Furthermore, Charles Henry Beeson in his work Isidor-Studien discusses the role of the Irish in the transmission of Isidore of Seville. Isidore (560-636) is used by Irish writers from very early on. The anonymous De duodecim abusivis saeculis, written 630-650, draws upon the Origines; Lathcen (661) upon the De ortu et obitu patrum; and the Pseudo-Isidorian De ordine creaturarum upon the Differentiae. Already in the seventh century, the Origines is used by Cennfaelad in his Auraicept Na n-Éces and by the lost “Old Irish Chronicle” from which all extant annals appear to descend. The Irish clerical scholars fixed on Isidore’s Etymologies calling it the Culmen, “the summit of all learning.”

The first Anglo-Saxon writers of importance, Aldhelm and Bede, begin to write in the 670s and 700s respectively; they both cite Isidore. Scholars propose that Aldhelm and Bede receive Isidore’s work throughIreland. For some sixteen years Aldhelm, founder of St. Laurence atBradford-on-Avon, had been a pupil of the Irish monk Máel-dubh. Mayr-Harting maintains, however, that “the Irish were not indispensable in introducing the Anglo-Saxons to Isidore’s writings.” Regardless of whether the Anglo-Saxons receive the works of Isidore directly, or by way of contacts with the Irish Celts, the literary presence ofSpain is strong in theBritish Isles during the Anglo-Saxon period.

Excerpt from the Dissertation

Copyright @ Jamie L. Higgs 2003

Visigothic Spain can be counted among the ecclesiastical and architectural influences working in Anglo-Saxon Britain. Influences fromIberiacould have been disseminated directly to theBritish Islesby way of contacts between Britonia and the North. Ideas from the south could be indirectly transferred by way of the same routes that Iberian texts travel to the North, through the general comings and goings of traders and ecclesiastics. In the whole process of the Christianizing of Anglo-Saxon society, and in the story of the establishment of Christian kingdoms which would ultimately merge into one kingdom, the native Celtic and continental contributions are all vital.

_______________________________________________________________________

Iberia and the British Isles … are not isolated enclaves as the scholarship of the past has proposed. Rather, it is the case that these geographical regions and their respective cultures are functioning as part of a much wider and interconnected early Medieval world.

________________________________________________________________________

The strands of multiple influences are interwoven in every kingdom and at every stage of the process by which the Anglo-Saxons become Christian. One of those strands which explains Eastern motives within the Celtic rite and Anglo-Saxon architecture ofBritainis the influence of Mozarabic rite and of the Visigothic churches in which it was practiced. All of this suggests that Iberia and the British Isles in the period under review are not isolated enclaves as the scholarship of the past has proposed. Rather, it is the case that these geographical regions and their respective cultures are functioning as part of a much wider and interconnected early Medieval world.

This dissertation employs a comparative method to examine the similarities between the church plans of Visigothic Iberia, the mid-sixth through the late-eighth century, and Anglo-Saxon Britain. The comparative study of these two architectural groups relies on evidence from the archaeological record, contemporary literary descriptions, and on-site analysis. Three aspects of church design are taken into consideration—elements used to achieve separation within the churches, i.e. chancel barriers, choir screens, and full walls; the presence of eastern chambers, i.e. sacristies; and complicated subdivisions. The use of these architectural elements is found to be similar between the Visigothic and Anglo-Saxon churches.

In order to account for these similar architectural features, the contemporaneous liturgies of these two periods, the Mozarabic and the Celtic, are analyzed for comparable liturgical practices. It is found that both rites possessed an elaborate ceremony of preparation, which would have required sacristies, as well as other comparable ritual formulae. Therefore, it is proposed that Visigothic and Anglo-Saxon architecture responded to similar liturgical exigencies. In addition, it is hypothesized that the Celtic rite, like the Mozarabic, is preoccupied with issues of separation between the clergy and the laity. Sixth-and seventh-century Spanish church councils address these issues and are, interestingly enough, attended by British churchmen from the British See of Britonia established inGalicia. Generally, it is found that the space considerations within Visigothic and Anglo-Saxon church architecture are remarkably similar as are their liturgical practices.

Furthermore, the architectural planning and liturgical practices of both Iberia and the British Isles recall Eastern, Syrian, liturgical practices and architectural planning. Such Eastern influences are known to have been present in Iberia and such ideas may have been disseminated to theBritish Islesby way of contacts between Iberia and the North. Historical, archaeological, literary, and epigraphic evidence are examined to establish the connections which existed between Iberia and the British Isles, demonstrating that liturgical and architectural influences between these two geographic areas are probable.

The celebration of the Eucharist was, and is, the most important function of a church. Architecturally speaking, the planning and design considerations of a church support the liturgy, and, like the liturgy, relate the worshipper to God and to each other. Architecture, therefore, helps determine the worshipper’s experience of the rite. The objective of this dissertation is to consider the observations of past scholars regarding the liturgical, literary, and artistic connections betweenIberiaand theBritish Isles, and to take such observations one step further by exploring evidence for connections reflected in church planning. I explore the relationship between the so-called Mozarabic liturgy and Visigothic church design and their probable influence upon the Celtic liturgy and contemporaneous Anglo-Saxon church planning.

________________________________________________________________________

… For a period of well over a century, the Visigothic kingdom is politically unified with an energetic church led by some of the most outstanding thinkers of the day. It is also the most stable and prosperous kingdom in Europe at the time.

________________________________________________________________________

Contacts with the East, resulting in liturgical and architectural elements with Eastern affinities, are clearly demonstrable for Spain and are summarized in Chapter II, which deals with the history ofSpainand the Visigoths. On the other hand, substantial and sustained contacts between the East and the British Islesare not so evident. J. N. Hillgarth observes that “most recent scholarship is agreed in finding considerable and clear evidence of Eastern influence on Irish artists in the sixth, seventh, and eighth centuries” but that “no specific study seems to have been attempted of how this Eastern influence reached Ireland,” the British Isles. In the same article, he suggests Visigothic Spain as the channel through which Eastern influences reached the North. In a later article, examining the affects of Isidore of Seville’s writings on the Irish, Hillgarth begins by posing the question “Is it not possible that we may have in Spain the link historians have been looking for between the East and theFar West?” He observes that art historians seem to have either completely ignored the possibility of artistic relations between Spain and [theBritish Isles] or to have been “content to dismiss them with a shrug of contempt.

Independently of Hillgarth’s suggestion of literary influences between Iberia and the British Isles, I too noticed similarities between these two geographic regions, particularly in the area of architecture. It was only after observing these similarities and investigating the subject further that I came across Hillgarth’s theories and his question posed to art historians. Considering his two premises that 1)Spainwas the link between the East and the North and 2) there were sustained contacts between Spain and the North during the Early Medieval period, I have undertaken a liturgical and architectural study in an attempt to expand the scholarship which explores the connections between these two regions. I agree that Eastern liturgical and architectural forms were present inIberia. In an expansion of Hillgarth’s theories, I propose that when Eastern architectural and liturgical forms are detectable in theBritish Islesduring the Early Medieval period, the purveyor of that influence wasIberia.

The problems I encounter in this study include the identification of the corpus of churches, both Visigothic and Anglo-Saxon, and, since there is no Visigothic or Anglo-Saxon church which is unaltered, the original forms of the buildings. The absence of scholarship identifying which liturgy is celebrated within the Anglo-Saxon churches and how such a liturgy could have related to the architectural spaces presents further obstacles. These problems are compounded by the surviving condition of the monuments. Most of the liturgical spaces have been changed to the extent that their Early Medieval ground plans can only be studied through the archeological evidence. Parts of the churches have been demolished or expanded and floor levels have changed. Elevations have also been altered. Those churches which continue to serve as places of worship usually have modern floors covering the originals. As a result, the original placement of architectural features, such as chancel barriers, has been obscured and is impossible to determine through direct observation. Furthermore, most of the liturgical furniture is no longer in situ having been reused or destroyed entirely. The provenance of the objects found in today’s museums is not usually recorded. Finally, in bothIberia andBritain extant churches are mostly rural. Judging from descriptions in contemporary sources, these extant churches only represent a small sample of those churches which are known to have existed. Because of their relatively small numbers and rural locations, the researcher cannot be sure that they are representative of the developments taking place in metropolitan areas where no such early churches have been identified.

I visited the Visigothic churches of San Juan de Baños, São Fructuoso de Montélios, Santa Comba de Bande, San Pedro de la Mata, and San Pedro de la Nave as well as the Anglo-Saxon churches of Saint Mary Reculver, Saints Peter and Paul in Canterbury, Saint Pancras in Canterbury, Saint Laurence in Bradford-on-Avon, and All Saints Church in Brixworth.

________________________________________________________________________

The strands of multiple influences are interwoven in every kingdom.

________________________________________________________________________

Caballero Zoreda states that the theory of Visigothic architecture is “like a whirlpool sucking in everything which fell within its grasp, converting everything into Visigothic, and thereby reinforcing its own attractiveness as a theory.” His work is guilty of the same. His theory “sucks in all that falls within its grasp” by contending that all architecture which exhibits any similarity to Santa María de Melque was influenced by Muslim, or Umayyad, design. He even finds Umayyad influences in Asturian painting in, for example, the church of San Julian de los Prados (Santullano, 812-842) (Fig. 12) which he says “may perhaps best be explained with reference to the mosaics in the mosque of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (687-692).”

Turning now to Anglo-Saxon architecture, there are three works which are especially important. G. Baldwin Brown’s is the oldest; it is basically a thorough catalogue of Anglo-Saxon church architecture concentrating on ecclesiastical architecture from the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to the Norman conquest. Brown’s study is still cited in the field of Anglo-Saxon church studies as he is credited with producing the first work which examined this subject in any detail. Brown’s important contribution is, however, surpassed by that of H. M. and Joan Taylor. I have been able to locate only four works which provide any account of Britonia, a settlement of British churchmen inGaliciathat tied Spain to Britain. Pierre David, Nora K. Chadwick, E. A. Thompson, and Simon Young cite information concerning the little known historical migration of Britons toSpainand their subsequent founding of the See of Britonia in Galicia. In all four works the information available to these authors is meager but very important.

To speak of Visigothic Spain is to refer to the oligarchic rule of eight million indigenous Hispano-Romans by a governing class composed of perhaps no more than 200,000 Visigoths. Nevertheless, their place within Iberian politics is firmly established by the mid-sixth century. Following a century of military consolidation throughout thePeninsula, which includes the conquest of the Suevi in the northwest of thePeninsulaby 585 and of the Byzantines in the southeast by 624, the Visigoths makeToledotheir capital. Having established a firm alliance with the orthodox bishops through their conversion from Arianism in 589, the Visigothic kings ofSpainsucceed in holding together the largest undivided political unit in seventh-centuryEurope. So for a period of well over a century, the Visigothic kingdom is politically unified with an energetic church led by some of the most outstanding thinkers of the day. It is also the most stable and prosperous kingdom inEuropeat the time.

When we turn our attention to the Anglo-Saxons we find a very different story. The Anglo-Saxons do not have to travel as far as the Visigoths to reach their new homeland.

Originating in northern Germany and Jutland(Fig. 14), they begin to arrive inBritainduring the mid-fifth century. Scholars now believe that there is no wholesale extermination of the native British population with the coming of Anglo-Saxon political power. Many contend that the Anglo-Saxon incursion, like the Visigothic, is superficial and that this incursion provides “little more than the veneer of a new language and a conquering élite on a British population which is not fundamentally changed, but remains in place despite military defeat, economic depression, and cultural deprivation.” Britons continue to be a particularly high proportion of the population in some parts of the country. In Kent, for instance, this is suggested by the survival of Romano-British administrative centers, craftsmen, and place-names, and in early Northumbria by the D. J. V. Fisher, The Anglo-Saxon Age.

The exact origin of the Christian religion in Britain is difficult to determine though the second half of the second century is generally accepted as the probable period in which it is introduced.

VISIGOTHIC AND ANGLO-SAXON CHURCHES—PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND CONCEPTUAL SIMILARITIES

The monuments built in Visigothic Spain during the mid-sixth through the late-eighth centuries constitute a cohesive group, the spatial considerations and architectural furnishings of which appear to have affected those of Anglo-Saxon Britain. Overall, Visigothic church plans have enclosing apses and complicated subdivisions. The churches are characterized by the extensive use of chancel barriers and choir screens as well as multiple chambers. A similar division of space and use of liturgical furniture is found in contemporary Anglo-Saxon churches.

The use of the architectural elements mentioned above begins to evolve in Visigothic Spain during the sixth century. These elements lie at the center of the architectural aesthetic that binds together the buildings of the seventh and eighth centuries, those traditionally called Visigothic. Traditional scholarship concerning Iberian architecture of the mid-sixth through the early-eighth centuries subscribes to two theories. The first is that the churches constitute a new monumental art of national unity which reflects the fusion of the Hispano-Roman and Visigothic peoples. Though this style is both new and cohesive, according to the second theory it is the uninterrupted continuation of an indigenous Roman tradition of building and design. Under the continuation theory, the Visigoths, contribute little or nothing to the building tradition. For example, Helmut Schlunk, states “Este arte no tiene nada de germánico, sino que es de puro abolengo hispanorromano, aunque con numerosos elementos norteafricanos y bizantinos.”

However, Dodds asserts “the assumption that the Visigoths possessed no building traditions of their own and so were not themselves involved in the physical act of construction obscures their probable impact as patrons or as significant catalysts for reaction and change in architecture and the society it served.”

End of Exceprt. The full dissertation is available on this web site.

Jamie L. Higgs is Associate Professor of Art and Art History and Chairperson of the Visual Arts Department at Marian University. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Louisville in 2002. Her areas of research interest include Medieval Iberia and the Classical World. She has assisted the Indianapolis Museum of Art in exhibition programming and is currently writing an article entitled “Medieval Iberian Architecture and Liturgy: Forms of Resistance.”

POSTSECONDARY LEVEL

L E S S O N P L A N T O A C C O M P A N Y

Some Observations on Visigothic Architecture and Its Influence on the British Isles

JOURNAL OF EMPIRE STUDIES SUMMER 2011

1. What is the authors’ thesis?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

2. How does she prove it?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

3. The author characterizes Visigoth architecture this way:

“Visigothic architecture is “like a whirlpool sucking in everything which fell within its grasp ..”

Is American architecture like that? In your home town, are there buildings where you see influences from different cultures? What are they?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

4. What should a church look like? Should all churches look old? Do you like Richard Meier’s Jubliee Church(http://wirednewyork.com/forum/showthread.php?t=4168&page=1)?

Which of these 10 churches is your favorite? Why?

http://www.neatorama.com/2007/05/07/10-divinely-designed-churches/

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

5. Archeology is just digging up things from the past – it shouldn’t be controversial, should it? Please read this article on an extremely controversial “dig” going on right now:

Controversy in Jerusalem: The City Of David http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2010/10/14/60minutes/main6958082.shtml

Do you think the archeologists should be allowed to continue? Why or why not?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

6. The author gives us a startling fact:

To speak of Visigothic Spain is to refer to the oligarchic rule of eight million indigenous Hispano-Romans by a governing class composed of perhaps no more than 200,000 Visigoths.

How could so few Visigoths rule 8 million people? Has this happened elsewhere, where a tiny number of “conquerors” rule a huge native population?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

7. What will archeologists in the year 3012 find when they dig up your home? What deductions will they make about you and the way you lived?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

How do the architecture of the other Germanic tribes from the time of the Visigoths differ from the Visigoths themselves? How are they similar? I believe that Visigoth style architecture made its way to England through the Saxons, another Germanic tribe that was brought the England by the Romans as mercinaries to fight the Celtic tribes in Scotland. After the Romans left the Saxons remained, and the Anglo-Saxons were born, they just kept many of their German cultures and influences. It is the same way that English is a Germanic language.