They Took The Words From Our Mouth!

LANGUAGE AS A COMPONENT OF EMPIRE

Native Language, National Literature and Cultural Revitalization in Colonialism: Ireland As A Case Study

Joe Reilly, Ph. D

Brian Boru, A King of Ancient Ireland

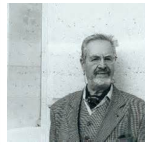

Dr. Douglas Hyde

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

The Irish language has been a focal point in the long bitter relationship between Ireland and England. In his provocative article, my colleague Joe Reilly looks at how a dedicated man named Douglas Hyde helped the Irish regain their language and with it their cultural inheritance. It is a pathway charted by two scholars, Fritz Fanon and Albert Memmi. Professor Reilly uses their theories to explain the mechanics of language assimilation.

As he points out, a handful of “big languages” – English being most prominent among them – now dominate world commerce and world culture. But that, he argues, is not an innocent or neutral phenomenon – dozens of “minority” languages are discouraged and even snuffed out to make room.

Celtic cross, a symbol of ancient Ireland

It quickly follows that cultural heritage of that population can die with its language. It is not an isolated process – Professor Reilly compares the Irish example to African and Israeli cultural revitalizations, as well as others we can see and hear around us today.

Professor Reilly writes the ways he lectures – extremely knowledgeable, often partisan, always provocative. He pulls in a wide-ranging and colorful host of causes and effects to his linguistic model of empire, from Mississippi barbecues to Navajo Code to Geechee . I hope you will look at the full text of his article, where he gives a more detailed account of “Marginal Men” as well as added theories of Fanon and Memmi.

INTERVIEW

1. Was the Irish attempt to construct a national identity ultimately successful?

Why or why not?

The cultural work of The Gaelic League / Connradh na Gaelge and other organizations constructed the modern Irish identity based on historical reverence. Hyde pointed out repeatedly Ireland’s culture was the only major European culture left uncontaminated by Roman Imperialism. Ireland’s culture is an anthropological and linguistic gem for understanding its culture and determining a blueprint for understanding pristine cultures.

The recent economic boom and bust, which mirrors the recent past for all nations, proved success of this cultural construction. Since Ireland is in the European Economic Union (EEU) they had an influx of guest workers from central Europe. Ireland accepted refugees from various nations in the world. Because of this modern linguistic mix the Irish language is spoken in public as a nationalist badge.

Today, everyone in Ireland’s schools must learn the Irish language. Now it is being put to use daily. It is a cultural success.

2. What forces ran counter to Ireland’s independence of language?

All traditional “West Briton” / pro – British / Unionist opinion saw Irish language revival movement and its literature movement as anti-Imperial by its very nature. Brendan Behan told a story of being in a bar in England where he and others were speaking Irish. They were thrown out of the bar for speaking Irish!

Douglas Hyde was aware as a trained lawyer of the Penal Laws of 1695 to 1829 which made it illegal to write one’s name in Irish on their store sign or write documents in Irish. He also was aware of legal precedents giving freedom to British subjects to go about their business without interference. He played up all laws and precedents giving British subjects the freedom to pursue their interests without interference.

3. Historians like Niall Ferguson might reply to your argument that Ireland suffered at England’s hands by stating that domination of one nation by another is a natural process in history, and that Ireland received benefits from its relationship with England. Is there any merit to that view? Does the “colonizer wins / colonized loses” model always hold true?

Ferguson (whose name means “Strong Man” in Irish) can be seen as an apologist for the British Empire. He gives a generalized view of “might makes right” in magazine columns, books and television interviews. He looks at the same facts I am look at for my research. He draws a different opinion from the same situations. He sees how a handful of “Big Languages” — English, French, German and a few others — now unite the world.

Yet many languages are used widely in today’s world. Thousands of languages disappeared in the last few centuries due to colonialism and linguistic oppression. Manx Gaelic is extinct due to British Imperialism. At least two dialects of Irish (Decies from Southwest Ireland and Roscommon from the West Coast, which was Douglas Hyde’s initial dialect of Irish) have gone extinct.

Ferguson and Dinesh D’Souza both see more advantage to English-speaking upper classes in all nations of the world than tragedy of lost heritage. The British built roads and buildings and bridges in Ireland. Some suspect they “managed” the Great Famine, which killed or displaced 4 million people in a handful of years, to their advantage. The advantages are clear. The losses are vast. Colonizers withdrew labor and food and kept strategic ports for years. All advantages to the colonized such as enforcing use of the English language was incidental: Imperialists never wanted to help anyone but themselves.

4. Are there other examples to which we can compare or contrast the Irish cultural revitalization? The Jewish cultures in the Diaspora? Native Americans? The rise of India, a former colony? African language and culture in America?

Cultural revitalization or preservation movements make fitting “compare and contrast” items. Robert Briscoe, the Orthodox Jew of Irish birth and culture, visited Israel in its early years. He said Ireland and Israel were similar. Both were ancient peoples with an ancient language but without a nation state for centuries. Israel’s diaspora was vast but there were always some Hebrew-speaking Jews in Israel. Ireland always had some Irish speakers in Ireland as well in all nations of the Irish diaspora.

Native Americans of the Cherokee Nation, Comanche Nation and Delaware Nation are actively preserving and teaching ancestral languages to their young people. Seventy-five per cent of all Navajo only speak Navajo due to the large number of their nation and isolation of their homeland. Cultural revitalization or preservation has continued for these various Nations. There were never laws against keeping their culture. The Federal policy was to encourage homogenization through schooling. The irony is the US Marines in the Pacific War of World War II had Navajo speakers use their language in voice communication.

The US Army in Europe had Comanche speakers use their language in voice communication. Neither the Japanese nor Germans could determine the language or its codes. Native American languages were important in national security in this last century.

India has so many languages that English is used as their common language. British colonialism could not eradicate native culture in India due to its complexity. Gandhi usually spoke English for that reason. Indian cultures retained their languages and pride yet find it useful to adapt to The Stranger’s language for efficiency.

African language and culture in the Americas is a mixed bag. Some isolated African slave descendants in parts of South America retained their language and were mutually intelligible to contemporary Africans from West Africa. American slaves were required to learn and use English. Adopting Swahili or any other African language is an attempt to establish a tradition but it is a tradition lost long ago. Cultural practices amongst Black Americans have roots in African cuisine and family relationships but there are only traces of linguistics left such as the Geechee of the American South.

5. What would Frantz Fanon and Albert Memmi think, looking back at the Irish experience in the 20th and 21st centuries? Do you see traces of Irish culture which have “won out” in England or America?

Fanon and Memmi described North African colonial experiences and French Imperialism. Parallels in their descriptions to Ireland show the commonality of Nationalism reducing Imperialism. Although the Irish Revolution occurred before North Africa’s anti-colonial movements these collective actions were very similar. I expect Fanon and Memmi would see Erin’s Celtic experiences against British culture and political power in reclaiming sovereignty as universal and applicable to Arab cultures against French culture and political power.

6. Do you see traces of The Stranger in today’s stories?

Ireland’s economic relationship with London was defined by Giovanni Costigan as Puerto Rico’s relationship with New York. Irish guest workers or immigrants abound throughout Britain. The Irish television network RTE/Radio Telefis Eireann produced original programming about Ireland. The television series Ballykissangel was about a small town in southeast Ireland. Everyone spoke English to each other. Two marginal characters spoke Irish at one point.

The primacy of the English language is ubiquitous. Although the characters would have been educated in speaking Irish the use of English is so mundane that The Stranger’s cultural presence is constant. Another series was Ros Na Run (which means Rose of The Secret ), which was almost entirely in Irish in a town in the West Coast. All of the Irish speakers shunned Bearla / English and no English was spoken in its dialog. This cultural uniformity ironically shows the modern Nationalist vow of Connradh na Gaeilge: “Speak English only when Irish is not understood.”

7. Do you see similar processes today? Do nations still ‘compete’ in language?

Do these same processes apply to Asians in America, or Moroccans in Germany?

Several decades ago it was pointed out by my Modern Europe professor that American English is now the lingua franca of international business. People who speak various languages usually all speak American English. Contracts are written in American English for that reason. Yet small groups of linguistic minorities remain. Some guest workers or immigrants will abandon their ancestral culture and others teach it formally or informally. I happened to see a Food Network program recently about barbecue restaurants in Mississippi. One Chinese family has operated a popular barbecue restaurant in Mississippi for three generations. This extended family was shown having a reunion.

All of them spoke with charming Southern accents. All of them could “code switch” into Chinese in a moment. Douglas Hyde said in 1905 he would encourage any Irishman or Irishwoman to learn English for commercial reasons. He would encourage them to speak Irish to retain their soul. This process goes on today in every nation where there is any linguistic minority.

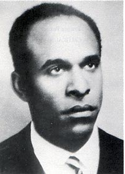

Language scholar

Albert Memmi

EXCERPT

They Took The Words From Our Mouth!

Native Language, National Literature and Cultural Revitalization in Colonialism:

Ireland As A Case Study

“The past is prologue” is a concept that holds for all individuals and all cultures.

The concept was first stated in ancient Greece. The idea remains practical wisdom. The past has identifiable patterns of thought and action. Any ideas from and about a nation’s past provide its members with expectations in the present as well as plans for the future.

Our understanding of our cultural past builds pride for personal and collective self-concepts. Role models of ancient heroes or contemporary notables are role models for anyone’s aspirations. Native role models have always been particularly important for nations that have been colonized. Yet these same self-concepts can become a threat to the colonizer.

Tacitus, the Roman Senator, said twenty centuries ago “Empires are not maintained by timidity.” A colonizer must degrade the culture of the colonized to establish and maintain control over the native population. Positive native role models improve the self-respect of the subject people. Even a prisoner in his homeland wants inspiration.

Colonial empires existed since ancient times. In 1900, more nations were colonies than were sovereign states. During the first half of the 20th Century most colonies became sovereign nations. A few colonies exist today. Six counties in Ireland are held by Britain.

Colonialists sought to control colonized people and to encourage them to believe they were inferior to the colonizer. The Irish language has the term An Gall, The Stranger, to define the foreigner who came, stayed and settled. Colonized people could not defend their homes nor protect their homeland from well-armed Strangers with bad intent.

Despite The Stranger’s occupation positive thoughts a colonial subject had about his homeland provided legitimacy for ancestral traditions. These traditions – that which is expected, repeated or attempted – depend on our understanding of the past. A colonial subject knew he was a loser, whether the defeat was in his lifetime or his grandfather’s lifetime. Every colonial subject knew every day he was politically subject to The Stranger (and local collaborators).

Colonial collaborators were “Marginal Men.” (the ‘margin’ is on the border). The colonial Marginal Man was on the border, or edges, of both cultures. This collaborator was on the edge of his culture and The Stranger’s culture. This Marginal Man was a small percentage of his homeland’s population.

Ireland’s revolution was the first modern loss to the British Empire.

Ireland’s Revolution began a year before the Russian Revolution of 1917. The Irish Revolution has been given scant attention by theorists of revolution. This lack of interest may be due to Ireland’s low profile in international power politics. Possibly it is due to persistent anti-Catholicism amongst proudly unchurched academics. Ireland’s revolution is a textbook case of a nationalist revolution.

Ireland’s revolution follows a pattern of national revolution noted independently by two scholars major Frantz Fanon and Albert Memmi. These theorists predicted nationalist revolution will originate from peaceful cultural revitalization. The next phase, they predicted, will be a peaceful political appeal for reform. The Imperial Mother Country will reject these cautious requests as too radical for its commercial and political interests.

Fanon and Memmi were socialized in French-speaking colonies. Each theorist defined language as the central dimension of colonialism. Language, they both felt, would become the central dimension of anti-colonialism. To them, language was equal to national culture. Fluency in two languages was participation in two cultures. Fanon said accepting The Stranger’s language and educational system negated self and community and was a personal form of moral prostitution. The upwardly mobile native intellectual became fluent and even eloquent in The Stranger’s language. The Marginal Man felt he was part of and belonged to The Stranger’s culture.

Fanon and Memmi believed that if the native language was rejected, this rejection would result in disillusionment within the colonized population. Some colonial subjects would resort to violent revolution to redress their grievance. Individuals leading the violent revolution would be Marginal Men.

The predictions made by Fanon and Memmi held true in the case of Ireland, its cultural revitalization, its peaceful politics, and finally the Irish armed revolution (although Fanon and Memmi described personal and group processes seen in Ireland’s Nationalist Revolution, neither writer mentions Ireland).

English monarchs wanted to eliminate Celtic culture. Ireland’s culture was much different from England’s culture and much older than England’s culture. The Romans did not invade Ireland. Ireland had the only major pristine culture and language in Europe. It is the oldest vernacular in Europe. Cultural homogeneity meant political and military success in colonization. Ireland’s language and native institutions were outlawed by British Penal Laws in Ireland from 1695 until 1829.

Fritz Fanon

Under British rule, Ireland’s stepsons and stepdaughters sought firm identity as “Irish,” not as British subjects. Cultural revitalization promoted all attempts for political equity for the Irish people. England’s Parliament was threatened by any political reform and opposed peaceful political requests for reforms in the 1800s. Queen Victoria rejected all reforms within her Empire. Victoria was unprepared to change anything to do with English colonial power. She was more comfortable speaking and writing in German than in English.

When the Potato Famine of the 1840s wreaked havoc on Ireland’s population, the British Empire’s relief efforts were inadequate, year after year. A legend still told in Ireland is Queen Victoria donated five pounds sterling to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. She then donated five pounds sterling to Irish famine relief. Her attitudes and actions earned her a unique name in Irish history: the “Famine Queen.”

In the decades after the Famine the Irish found a newfound cultural vigor.

Marginal Irish were especially disillusioned by the failure of peaceful politics in activating the Home Rule Bill of 1912. This legislation would have secured more just treatment for Ireland. Some culturally conscious Marginal Men were motivated to join the firestorm of national revolution aimed at a new goal. They did not want to make Ireland a Dominion within Britain’s empire. The new aim was to establish the Republic of Ireland.

A new dimension of Irish nationalism developed and became the cultural standard. Revolts were funded by American emigrants and their children who had left during the famine years. This population gave arms and money for the War of Independence in the 1920s.

Language itself became a battleground. The Irish people developed a form of English that reflected ancestral sound patterns, rhythms, word choices, idioms and sentence structure. One distinction of Irish is it is unique in not having words for “yes” or “no.”

If an Irish speaker is asked if they like something the answer will either be “Is maith” which translate as “It is always good” which is roughly “yes.” The answer of “Ni maith” translates as “It is never good” and is roughly “no.”

Ireland’s situation also improved because of England’s larger problems. The Irish language was the engine of Ireland’s new cultural and intellectual movement. The founder of the movement was Dr. Douglas Hyde who was the son and grandson of Anglican ministers. Dr. Hyde founded The Gaelic League (or An Connradh na Gaeilge). An Connradh worked to encourage the Irish people to speak the Irish language again. The League’s work was always to restore Irish as the nation’s primary language. Dr. Hyde and his contemporaries understood the importance of language and devoted their efforts to popularizing Irish culture.

In 1892, Dr. Hyde delivered an address that began the revitalization movement (he published it as a pamphlet later that year). His argument was entitled “The Necessity for De-Anglicizing Ireland.” It was a revitalization embraced by the citizens. I was once told by a native Irish speaker: “They took the words from our mouth.”

No longer. Being Irish and speaking Irish became a mark of achievement and pride.

It was no longer a mark of national and cultural inferiority. Ireland’s national shortwave radio station, 2RN or “To Erin” was a powerful cultural effort that helped bring back Irish culture. 2RN was established to counteract British Broadcasting Company radio programming in English.

Literature is the creative use of a language. Literature has proved another powerful vehicle for Irish cultural revival. Proverbs, poems and tales excited the Irish imagination. “Marginal” poets like William Butler Yeats, Lady Gregory and John Millington Synge were Anglo-Irish. They wrote poems and plays in English. Yeats, Synge and Lady Gregory had never learned to speak Irish (since they were Anglo-Irish, descendants of colonial garrison members.)

New writers like James Joyce celebrated traditional Irish culture in their modern works. These plays and poems extended the Nationalist Movement as entertainment for anyone who could understand English. The logical development of a national culture as the basis of a sovereign nation was suggested to everyone in their audiences. Poems and legends of Ireland’s past were collected, transcribed then printed. From the 1890s until the 1920s two thousand Gaelic League chapters met weekly. Fifty thousand well-educated prosperous opinion leaders spoke Irish and talked about literature and about Ireland’s place in the world. All seven signatories of the Irish Proclamation of Independence in 1916 were connected to the language movement. Each of them — Padraig Pearse, Seosamh Plunkitt, Thomas MacDonagh, James Connolly, Sean MacDiarmada, Eamon Ceannt and Thomas Clarke — was a published poet.

Standish O’Grady was an Irish author who brought back the culture of Ireland’s past. He was a proud Anglican native of Dublin who authored novels and histories on Ireland’s past glories. O’Grady was known to speak his mind despite any consequences.

He proclaimed in 1899:

“We now have a literary movement, it is not important.

It will be followed by a political movement.

That will not be important.

Then must come a military movement.

That will be important indeed.”

(Quoted in Thompson, 1969: 61 – 2, 113; Dangerfield, 1976: 137).

These words turned out to be prophetic. And the Irish Revolution turned out to be the beginning of the end of the world’s largest empire.

# # #

Hi, Tom!

Thanks for publishing my article.

The illustrations add greatly to the text.

Joe.