“The Lion King” and Its Message of Social Darwinism

A Cultural Critic Sees Undertones of Fascism in the Popular Story

Dan Hassler-Forest

Photo copyright @ 2018 Walt Disney Company

Introduction

In this smart, provocative article and interview, cultural critic Dan Hassler-Forest warns us that loaded images and ideas may lurk beneath the surface of the most innocent-looking story. His thesis is that the widely popular Disney story, “The Lion King,” has at its heart a love (or at least an acceptance) of fascism. The inherited right of Simba and Mufasa to lord it over the lower animals of the veldt is presented as a fact, and their absolute authority is never questioned.

Dan Hassler-Forest is far from alone in his consideration of tyranny as it appears in children’s literature. A surprising number of dissertations delve into the wizarding world of Harry Potter and its portrayal of tyrannical villainy (Valdemort is characterized by scholars as the equivalent of a wizard Hitler) as well as the chokehold which the oppressive Ministry of Magic puts on Hogworts. Author J.K. Rowling includes explicit thinking on the subject in “Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince:”

Voldemort himself created his worst enemy, just as tyrants everywhere do! Have you any idea how much tyrants fear the people they oppress? All of them realize that, one day, amongst their many victims, there is sure to be one who rises against them and strikes back!

Other young-reader narratives engage the question of tyrants and tyranny, often in their depictions of all-powerful villains (Shadowfell, Catching Fire) and regimes (A Handmaid’s Tale, 1984, Fahrenheit 451). In his riveting, tragic novel about schoolboys abandoned on an island, “Lord of the Flies,” William Golding gives young readers a chillingly clear message. He shows how the well-meaning boys begin in democracy and, good faith and then, step by agonizing step, descend into tyranny. George Orwell’s remarkable “Animal Farm” offers a similarly bleak portrait of communism.

An arguably more pro-tyrant children’s story is Roald Dahl’s 1964 novel, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (adapted to screen in 1971 as “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory”). In this fascinating fantasy, an all-powerful, bizarre dictator and candy baron dictates matters of life, death, and destiny, without anyone questioning his authority.

_________________________________________________________________________________

No matter how you look at it, this is a film that introduces us to a society where the weak have learned to worship at the feet of the strong.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Hamlet Comparison “The Lion King” is a favorite for interpretation by scholars like me. One line of thought compares Simba’s story to that of Shakespeare’s tragic hero, Hamlet. Like Hamlet’s father, Mufasa is murdered by his own brother, who wants to take the throne. Like the Prince of Denmark, the Prince of the Savannah first runs from his responsibilities (“Hakuna matata”) after his father’s death, but later returns to avenge that death. In the end of both tales, the evil uncles wind up dead, though Simba shows more mercy than Hamlet.

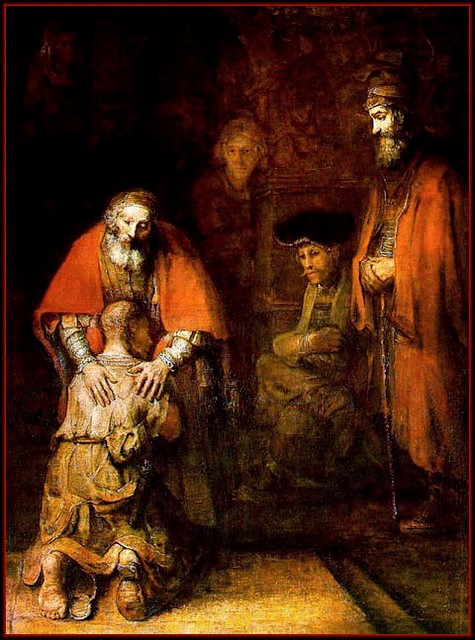

“The Lion King” as a Christian text. Other scholars see biblical echoes in “The Lion King,” Jonathan Barfield of “Philosophy Now” points out that the relationship between Mufasa and Simba mirrors that between God the Father and Jesus the Son. Rafiki the baboon says, “He lives in you.” Similarly, God lives in us, and is always watching over us.

When Simba says, “I just needed to get out on my own, live my own life, and I did, and it’s great,” Bible scholars see strong similarities to Jesus’s Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11 32). In the parable, the son thinks he can live better without the responsibilities he has while living with his family, and so leaves to live in a ‘far country’. This is exactly how Simba behaves, before returning as a savior figure.

which bears some similarity to “The Lion King” plot.

Interview with Dan Hassler-Forest

| August, 2019 |

1. What are three ideas you would like young viewers of “The Lion King” to consider?

If we’re talking about young children: they are still working to make sense of the world, and the roles that may be available to them in it. Many Disney movies offer them narrative frameworks that help them imagine what it means to move from childhood to adulthood. A question to ask them to consider would be: what does it mean to grow up? What kinds of adult behavior does the story provide? For teens and young adults, there is a stronger awareness of how society is organized, and how their behavior is constrained by power relationships. For them, it is more useful to ask how power is organized in this society, how it relates to their own experience of the world, and whether the worldview on display in the film is (or isn’t) compatible with their own values. This could help them draw their own conclusions about how social and political structures are reproduced through popular media and children’s stories.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Disney movies offer children narrative frameworks that help them imagine what it means to move from childhood to adulthood.

_____________________________________________________________

2. How would you re-write TLK to ameliorate the ‘fascist’ problem at its core? If Pixar had made it, how would TLK be different?

One thing that could at least make the problem more visible would be to tell the story from the hyenas’ point of view. If we were to follow a young hyena cub whose hopes and dreams of leading a decent life had been eroded by being forcefully consigned to the margins of society all their life, we would have an entirely different perspective on the lions’ autocratic power, and what it means to grow up under the iron boot of tyranny. It’s no coincidence that there are no hyena cubs anywhere in the film, as these social outcasts must be seen as deserving of their fate, and never as in any way “innocent.” Of course this wouldn’t make the organization of the movie’s society any less fascist, but it would give us an entirely different perspective on its power structure.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Mufasa’s pleasant-sounding but profoundly weird “Circle of Life”… provides a very thinly-masked rationale for social Darwinism.

__________________________________________________________________________________

3. One consideration often noted is that “The Lion King” is basically “Hamlet” – an uneasy prince at the center of murder and intrigue, with Timba and Poomba as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Scar as Claudius, and Nala is Ophelia (also, the father returns as a ghost.)

Another interpretation is that TLK is a Christian story (Simba is the Prodigal Son, Scar is Satan, Mufasa is God the Father, and Simba’s return to the Pridelands is Jesus’s Second Coming), while a third perspective sees the story as an existentialist parable.

Which is ‘true’? Are animated movies political? Is it unfair to burden them with too much symbolic meaning? Does it take away from our enjoyment of them?

One of the nicest things about stories is that they are there for us to interpret rather than providing a single fixed meaning. And our interpretation of a story derives from an enormous variety of factors, not least of which the social and cultural context in which we produce them. This explains why many people see many different things in a movie like “The Lion King.” But in my experience, the majority of our interpretations of these kinds of stories tend to be at the level of the individual character (what does Simba learn from his experiences? what parallels can we find in literary and cultural history?) rather than at the political level (what kind of power relationships define the world these characters inhabit? how do they correspond to political systems we know from human history?). So while these more personal interpretations are certainly valid, I try to stimulate students and readers to look at these texts from a more political perspective, in part because it helps them understand how social systems of power reproduce themselves through media.

4. One of the most powerful sentences in your article is this one:

When we consider that Mufasa is really explaining to his own heir why it’s perfectly fine to behave dictatorially, the lions’ perspective feels a lot more unsettling.

What does that mean? How can young TLK viewers process this idea?

Children have a very strong sense of social justice, so it’s very natural for Simba to point out to his father that rather than “respecting” the leaping antelope (as he just explained), they actually eat the antelope. Mufasa’s pleasant-sounding but profoundly weird “Circle of Life” answer provides a very thinly-masked rationale for social Darwinism. If we translate it to human terms, it’s as if a child asking a rich parent why it’s all right for them to be billionaires while other people live in poverty. The father’s answer would be something about “maintaining balance” in the world, since a small minority of the rich (the top of the food chain) were simply meant to rule over the poor. Of course, Simba’s response is then simply to internalize this ideology, and look forward in great excitement to all the privilege that awaits him once he’s all grown up. I think that young viewers would see this tension very easily once they become aware of the fact that the movie isn’t really about lions, but about what it means to have enormous power and privilege in the human world. Then asking them what they might do differently from how the Pridelands are organized could lead to interesting conversations about power, ambition, and social justice.

______________________________________________________________________________

There is a very obvious caste system in “The Lion King,” which is not only clearly visible, but which is also enormously rigid.

_____________________________________________________________

5. Is “The Lion King” an African story? An American story? A British story? How would it be different if it had been Chinese?

I would describe it very much as an American story that uses elements from other cultures (especially from African cultures) as a kind of window dressing to make it seem more exotic. In the same way that the Elton John songs featured on the soundtrack are very clearly American pop songs with African-sounding choruses and an occasional line of Swahili thrown in, the story is very much a familiar Western narrative about individualism, family, and personal responsibility with a few dabs of eye-catching but functionally insignificant cultural appropriation. A big difference with many other cultures (including many indigenous mythologies from non-Western contexts) is that there tends to be a much stronger sense of collective rather than individual identity. Thus, the strictly hierarchical worldview of “The Lion King,” with the lions at the top and the hyenas at the bottom, would most likely be much less present in a Chinese telling of a similar tale. (See also this article by Ida Yoshinaga on cultural appropriation in Disney’s Moana.)

6. Is there a class or caste system among the animals in “The Lion King”? How does this compare to societies in other Disney movies, such as “Bambi” and “The Jungle Book”?

Yes, there is a very obvious caste system in “The Lion King,” which is not only clearly visible, but which is also enormously rigid. The problem, again, is that clearly identifiable human social groups are depicted metaphorically as animal species organized as a “food chain”: predators (lions), prey (herbivores), and poachers (hyenas). Whereas actual hyenas are predators and lions are matriarchal in their social structures, these fictionalized depictions of animals make “The Lion King” into an allegory for a form of class struggle in which the hyenas are the only ones who are unsatisfied with the organization of power. “Bambi” has a similar focus on patriarchal traditions, in which men have all the authority and women only exist as maternal nurturers. But it doesn’t use animal species as metaphors for class distinctions – in part because the story’s world also includes humans, and the deer, rabbits, and other cute and cuddly characters are more literally animals. The same thing holds true for “The Jungle Book,” which is seen by many as racist for using King Louie and his monkeys as ethnically coded minority characters who dream of being white and powerful (“I Wanna Be Like You”), but in which predators like Shere Khan are certainly not pictured as divinely appointed authority figures. A more recent film that features a rather complicated use of animal species as allegorical fable figures for human societies is Zootopia, where predator-prey relationships are used to foreground issues like racism and sexism.

7. In current children’s literature or, more broadly, children’s culture (films, games, television), which narratives give you hope for the genre? Which stories worry you?

Hayao Miyazaki’s films have always given me hope for the genre: not only have they consistently focused on urgent societal issues like climate change and care for the environment (again, something that children respond very strongly to), but they are always critical and mocking in their depiction of the powerful, and they focus on compassion and learning rather than competition and romance. Many recent American children’s animation series have also offered socially engaged and progressive quality storytelling (Hilda, My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, the recent She-Ra reboot), all of which playfully and subtly introduce young children to larger social justice issues while also offering appropriate (or at least: inoffensive) role models and stories. I also think the ways in which the Star Wars movies have developed in the past decade provides a very hopeful political direction for this kind of franchise.

8. A huge percentage of parents in children’s literature do not make it past the opening scenes. Is all this matricide and patricide too dark for a children’s tale?

Fear of abandonment and even more specifically fear of losing a parent is one of the most overwhelming and universal anxieties for children. It’s probably not surprising therefore that so many children’s stories involve the (temporary) loss of a parent in some way – in part because they help young children imagine what it might be like to be in an intimidating situation without a reliable adult to help them through it. But while there are many ways in which a story can isolate a child and have them fend for themselves, Disney movies have really made the “dead parent trope” into a veritable cliché. I do think that both the oft-repeated pattern of one or more dead parents has been overplayed by Disney features, as has the insistent focus on romantic heterosexual relationships, which young children really have very little interest in.

# # #

DAN HASSLER-FOREST’S ESSAY

‘The Lion King’ is a fascistic story. No remake can change that.

No matter how you look at it, this is a film that introduces us to a society where the weak have learned to worship at the feet of the strong

Link: