The Generals

LEADERSHIP AND THE WAY WE FIGHT WARS

American Military Command from World War II to Today

THOMAS RICKS

Introduction

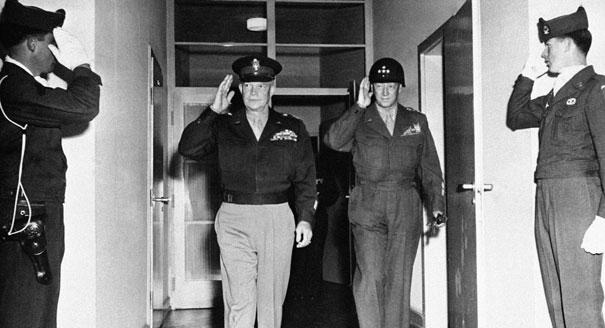

Colin Powell and Norman Schwarzkopf

Much is written these days about teaching leadership. I’m not sure we know how to actually teach leadership in classrooms. If we can, this is the book to do it: The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today is the closest thing we have to a textbook on the subject drawn from real people in the real-life enterprise of war. Ricks gets his hands dirty. We see specific incidents and the vivid details of leadership, both good and bad, in action.

Thomas Ricks’ remarkable book The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today is as excellent as it is ambitious, and that is saying something. Over 500 pages (including notes), The Generals takes on a most sprawling and complex story: the story of American military leadership from World War II to today.

In a work with such a giant and comprehensive exposition, it is easy for an author to get lost in the research, cluttering up the storyline with many learned digressions. Not Ricks. The Generals is so successful, I think, because it is all second nature to the writer. He seems to know all this automatically, and does not call attention to all his own detective work (I certainly would). Ricks’ delivery of anecdotes and observation is effortless. The reader does not feel like he or she is working hard to follow the story, and to see its themes emerge.

Thomas Ricks is well versed in all the fundamentals of writing. His prose in The Generals is an excellent example for my English 102 Research and Analysis students as they learn how to conduct research, construct an essay, and weave multiple perspectives into an effective long essay. His thesis is powerful and provocative, and he is careful that his fact-filled exposition is always in support of it. The reader is never far from the author’s narrative line – a remarkable quality for a book on such a vast topic.

Interview With The Author

Interview with Tom Ricks, fellow at the Center for New American Security and Pulitzer Prize winning author of Fiasco, The Gamble, and, most recently, The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today, which includes an extensive section on the decline of generalship and its impact on the Vietnam War.

Interview conducted by Jason S. Ridler, Ph.D. – 20 March 2013

In The Generals, you argue that since the Second World War, US Generalship has been in decline. Strategic thinking and accountability for failure (in the form of relief of command) have faltered and been replaced by more tactically oriented generalship and lack of accountability. What led to this decline as the America became more actively involved in the Vietnam War in the early 1960s? What was the immediate result?

I don’t know what led to the decline in accountability in the Army in the ‘50s and ‘60s. I suspect three factors were in play:

–First, in small, messy, unpopular wars, it is more difficult to know what success looks like. (Though there are some clear instances, such as the performance of Ridgway in Korea and Petraeus in Iraq.) Also, the Army is warier of relief in these wars, because removing people can provoke questions from members of Congress.

–Second, the Army generals of the 1960s tended to be the most successful battalion and regimental commanders of World War II, and because they had risen so quickly, they often didn’t get much military education. They tended to think, Hey, we beat the Nazis, how could an Asian peasant army give us a hard time? But in Vietnam, simply delivering firepower turned out not to be that effective. Westmoreland, mainly an artilleryman by training, boasted that he had attended only two Army schools—parachute school and cooks and bakers school.

–Third, there were major changes in the American military establishment in the 1950s. With the emergence of the Cold War, you got a big bureaucracy—and as Robert Komer observed in his terrific analysis of the Vietnam War, bureaucracies do not what they need to do, but what they know how to do. The Army specifically was a an institution adrift in the 1950s, not knowing what its role was in the new era of nuclear weapons, or whether there was a place for ground forces at all. At one point, its budget was half that of the Air Force, which was getting new planes and missiles and opening bases overseas. In response, Maxwell Taylor, when he was chief of staff in the late 1950s, steered the Army toward what he called “brushfire wars.” And Vietnam looked to some like a fine test case.

Altogether, this resulted in a real wariness of relieving failing officers, which had been the American military tradition. In World War II, some 15 division commanders in the Army were removed for combat ineffectiveness. To my knowledge, only one Army division commander was relieved in Vietnam. And I don’t think the generals of Vietnam were 15 times better than the generals of World War II.

One argument that emerges in Vietnam is that senior leadership, civilian and military, gave lip service and little more to the fact that they were facing a mix of conventional and insurgent warfare. Many point to Westmorland as the primary villain in this regard: refusing to embrace or appreciate the unconventional nature of the war. Would you concur?

Pretty much yes, though I think Taylor is more to blame for getting us into Vietnam than Westmoreland is. That said, both failed in what Clausewitz says is the first task of the senior commander—to understand the nature of the conflict in which one is engaged.

You also establish the failure of leadership in the wake of the My Lai Massacre. I recall reading your blog (BEST DEFENSE) while you were research this subject and how upsetting it was for you to read. How and why does My Lai support your contention of the failure of strategic leadership and vision in the US Army in Vietnam?

To me, the killing of more than 400 Vietnamese civilians, and the rape of dozens of women and girls, by American troops, with officers present, represented a moral collapse of the Army. We tend to misremember My Lai as resulting from the actions of one rogue platoon. It was not. It was a two-company operation, with the battalion commander and the brigade commander present at times. The Army’s official investigation concluded that the division commander, Samuel Koster, was part of the cover-up, almost certainly aware of the felonious destruction of documents. Ray Peers, the general who led the investigation, concluded that Koster lied to him. Yet Koster, having brought more disrepute on the Army than perhaps any general since Benedict Arnold, was not kicked out of the Army. He was not even court-martialed. He was demoted one rank, to major general, transferred to Aberdeen, and allowed to remain in the Army for some time.

To me, that represents a huge, screaming failure of accountability. The only redeeming factor was that Peers conducted a thorough and honest investigation, under great pressure, both in terms of time and politics.

Book review

The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today

If I told my faculty colleagues that I intended to write a history of American generals over the last 75 years, along with the wars they fought, they would take me aside and talk me out of it. It took Thomas Ricks five years to write this, but the effort was well worth it. The Generals is a rare and brave book, delivering a clear-eyed history of the modern era of American military leadership.

The Generals needs to be read by all our high school and college students. They will be fighting in and paying for our next war, one way or another. For all the theoretical writings on leadership, here is one that shows the consequences of leadership style and decision-making in real time, often measured in real lives.

Ricks casts a clear light on a full roster of military leaders, dwelling on well over forty subjects. Among them:

World War II

George C. Marshall. Ricks casts Marshall as a pivotal figure, “primarily a soldier” yet a superior leader in many ways. As captain, Marshall risked his career in speaking up to Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing. Marshall’s “greatest attribute was his ability to reduce complex problems to their fundamentals.” His ideas about what makes a good leader proved to be a powerful influence on 20th century generalship.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, of whom Ricks writes, “The genius in selecting Dwight Eisenhower was to recognize the potential match between Ike’s qualities and the unique challenges of being the supreme commander of a multinational force in a globe-spinning war.” Particularly in relation to MacArthur, Eisenhower is portrayed as a general who embodies many of the virtues of good leadership.

This is a story about a remarkable group of men.

George Patton. The “specialist” in military pursuit is portrayed as “strange, brilliant, moody,” an outlier to the Marshall leadership model, a natural warrior too tempestuous to be a good manager. Patton and Eisenhower were close friends, and Ricks clearly admires Patton for his dynamism and color.

Mark Clark. An Eisenhower general whose “approach in a crisis tended to be to blame everyone but himself,” Clark “should have been removed from his position.” His German foe, Kesserling, took advantage of Clark’s aversion to risk. Ricks points to Clark’s survival in a leadership position as a sign that our military was going wrong: “There is much more of Clark than there is of Patton in today’s generals,” he concludes (ominously).

Korea

Matthew Ridgway. Ricks reserves some of his highest praise for Ridgeway. He admires Ridgway’s “strong democratic streak,” refusing as he did to use a platform to address his men. “Looking into their eyes tells you something,” said Ridgway, “and it tells them something, too.” Ridgway knew what he wanted in his leaders and did not hesitate to relieve of their command those who did not measure up. Ricks credits this general with turning around the Korean War.

Douglas MacArthur, “general as presidential aspirant” and “useful idiot,” marks the end of the old order to Ricks. “He does not fit the Marshall template of the low-key, steady-going team player,” and that is putting it mildly. MacArthur is seen as a general with an “abrupt, emotional and highly personal” style of leadership who was capable of taking credit for others’ accomplishments.

American generals were managed very differently in World War II than they were in subsequent wars.

Vietnam

Maxwell Taylor, who led the Vietnam generation of generals, is cast as an intensely political man who advised Kennedy to enter Vietnam without understanding the implications. Taylor, writes the author, played on mistrust among generals and “made a habit of saying not what he knew to be true but what he thought should be said” in order to extend his own influence.

William Westmoreland is portrayed as the wrong pick to command in Vietnam. “He is spit and polish, two up and one back,” warned on one his peers. “This is a counterinsurgency warm, and he would have no idea how to deal with it.” Ricks recounts that Westmoreland’s command of military efforts in Vietnam suffered from a lack of strategic direction.

William DePuy catches blame in Rick’s narrative, for his “insistence on a tactical focus and the parallel repudiation of Gen. Cushman’s call for a broader-minded, deeper-thinking sort of senior officer.” Ricks cites another general regarding DePuy’s basic error: “He misunderstood the nature of the war, downrating pacification and emphasizing massive search and destroy operation.” DePuy inadvertently contributed to what Ricks refers to as “the collapse of generalship in the 1960’s.” Lyndon Johnson was another contributor, increasing the divide between military leaders and civilian decision-makers.

Iraq

Colin Powell was, in Ricks’ view, “adroit in working in the political world of Washington” and thereby avoided the clashes that his colleague Schwarzkopf encountered. Ricks spends three chapter on their involvement in “the empty triumph of the 1991 Gulf War” and its haunting aftermath. Powell was determined not to repeat the mistakes of Vietnam, yet in Ricks’ view he made a few of his own. For one, Powell was among the leaders who “missed the message of the Battle of Khafji, resulting in a war plan that instead of destroying the Iraqi military pushed its most important units back into Iraq.”

Tommy Franks comes under sharp criticism from the author. “If Norman Schwarzkopf embodied both the qualities and limitations of the post-Vietnam military, Tommy Franks was the apotheosis of the hubristic post-Gulf War force. Like Schwarzkopf, Ricks refused to think seriously about what would happen after his forces attacked.” The hubris Ricks refers to cropped in warning signs that his superiors ignored, permitting the inattentive Franks to remain far too long, according to Ricks.

David Petraeus is compared favorably to Matthew Ridgway as a general “arriving and soberly reassessing the situation and then, through clear thinking and impressive willpower, as well as taking advantage of changes on the ground, putting a new face on it.” Ricks also credits Washington overseers for their involvement after the Iraq setbacks of 2006. “Not a single general has been removed for ineffectiveness during the course of this war,” advisor Eliot Cohen advised President George Bush.

When the military does not relieve senior generals, civilian officials will.

Thomas Ricks is able to set these men and their leadership styles into context, comparing and contrasting them with one another and with generals like Terry Allen and Montgomery. Through Ricks’ narrative, we can see their actions from the vantage point of their soldiers, their peers, and their civilian overseers. I never felt the author had an axe to grind.

Components of what emerges from the book as a portrait of the good general can be found in Chapter One, where Ricks describes George Marshall and the type of leader he was looking for: “optimistic and resourceful, with relentless determination … generals who would fight, but not men who would command recklessly. “Above all, Marshall looked for “steady, level-headed team players. He wanted both competence and cooperativeness,” and valued effectiveness over appearance.

Again, in Chapter Two, Ricks directly addresses his topic: “In other words, successful generalship involves first figuring out what to do, then getting people to do it. It has one foot in the intellectual realm of critical thinking and the other in the human world of management and leadership. It is thinking and doing.” Another trait that Ricks spotlights is “the almost mysterious” ability to sense battlefield developments (Chapter 4). Knowing and exploring the terrain (as opposed to ‘roadbound’ officers) is another component of good generalship in Ricks’ view, (Chapter 12), as is empathy: “Knowing how to read the mood of soldiers is also part of being a general.”

A private who lost his rifle was now punished more than a general who lost his part of a war.

A second level of information in this book on leadership is, of course, a generous helping of military history. For a layman like me, Ricks brings to light the inner workings of the total war effort a nation puts forth (not just the combat, which it turns out is only a small part of the whole). I have gained a clearer insight into the differences between Korea and Vietnam, Vietnam and Afghanistan, and especially World War II and all that followed.

A third level of exposition is how America shapes its institutions, and how the nation has changed over this span of recent history. “When we understand the Army, and especially the changes in its generals,” writes Ricks, “we will better understand where we are as a nation and why we have fought the wars we have in the era of the American superpower, from Sicily and Normandy to Saigon, Baghdad and Kabul.”

Here he quotes historian Faris Kirkland, Army veteran of Korea, who found little difference between the performance of Marine and Army troops in Koreas:

But in their more senior officers – majors, lieutenant colonels, colonels and generals – he detected crucial distinctions. “Marine commanders at Chosin demonstrated knowledge of tasks, obstacles and the means to overcome them” wrote Kirkland. “Army commanders showed dash, bravery and hope: but little understanding of such matters as communications, reconnaissance, fire support and logistics.”

Part IV covers the interwar period between Vietnam and Iraq. Here is Ricks’ oveall or establishing view of the state of our military at this point on the timeline:

Coming out of Vietnam, the Army was shattered … As in the 1950’s, it faced a basic question. This time the issue was whether it could exist without a draft. Over the following twenty years, it would remake itself. It recruited a force of volunteers. It revolutionized how it trained soldiers, with far more realistic field exercises. It overhauled its doctrine of how to fight. It developed an array of new weapons. Almost everything about it changed but its concept of generalship.

As he notes in the Prologue, Ricks looks more at leaders in the Army over the other services (I wonder what he would make of Admiral Hyman Rickover, General Hap Arnold or General Curtis LeMay) and prefers the European theatre of World War II over the Pacific.

George C. Marshall in France

# # #

This review is very useful.

I hope to read this book and Ricks’ other works this summer.

Joe.