The Architecture of India

BOOK REVIEW AND AUTHOR INTERVIEW

The Architecture of India

India: Modern Architecture in History

Skyy, Powai, Mumbai, 2013 (Urban Studio)

by Peter Scriver and Amit Srivastava

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

Architecture is classroom gold.

When I begin a critical thinking assignment by handing out a photo of Falling Water,

the classroom goes silent. “Is this good architecture?” I ask. Hands shoot up in the air — instant engagement !! I then ask my students to write 240 words on why Frank Lloyd Wright’s master-work is either great or terrible, and why, and how it compares to the classroom building we are sitting in right now.

Students love architecture. No one has ever asked their opinion of Zaha Hadid, or Frank Gehry, or the design of their grandmother’s house. They have lots to say, and they are happy to get a teacher’s help in constructing their case for or against Louis Kahn’s Exeter Library (we hold debates, Mies van de Rohe versus Sam Mockbee, Wang Shu versus I.M. Pei, on and on).

From this first step, my classes and I are drawn into a consideration of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial, Gaudi’s cathedral, and whether their laptops of their toothbrushes better display the values of good design. As every teacher knows, once you have this type of engagement, you can move into any number of related fields – sociology, industrial design, war, architecture in movies, and many more.

“India: Modern Architecture in History” by Peter Scriver and Amit Srivastava, is a smart, well-written book on a most abundant subject – two subjects, really: modern architecture and modern India. It is a gift for a classroom that never stops giving.

The story of India’s 20th century is unparalleled. Authors Peter Scriver and Amit Srivastava are essentially telling this story through the built environment. They allow us to consider the history alongside the designs, as it should be. We cannot understand the Taj Mahal without a grounding in the Mughal Empire; or the British hybrid Rashtrapati Bhavan without knowing all about the Raj (and Kipling); or Chitra Vishwanath’s Yellow Train School without first tracing the life of Mahatma Gandhi.

One reason this book is so good may be that it represents a mission – to bring good architecture to all of India. Here is how the authors put it:

By recognising the architectural profession as part of the larger political economy of construction, we can develop a more robust understanding of architecture in the broader and bottom-up sense of the culture of building.

It is probably best for general-interest students to take such rich content in small portions. I might take a page and a photo and assign it as a critical thinking challenge, or perhaps of progression of three buildings, asking students to write about the progression.

The postscript to this vast and compelling narrative is surely the recent awarding of the 2018 Pritzker Prize to Balkrishna Doshi. He is a Mumbai-educated architect, a figure whose work embodies so many of the themes within the Scriver/Srivastava book. Doshi studied with both Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, and has taken that modern, Western aesthetic and applied it to housing for India’s working classes. “Infused with lessons from Western architects, he forged his artistic vision with a deep reverence for life, Eastern culture, and forces of nature to create an architecture that was personal,” the Pritzker citation stated.

We all need to be amateur scholars of architecture. I urge teachers, students, and general readers to give this remarkable book a read.

Walkway by Pritzker Prize winner B.V. Doshi

BOOK REVIEW

India: Modern Architecture in History

by Peter Scriver and Amit Srivastava

Authors Peter Scriver and Amit Srivastava tell a grand narrative that contains a score of smaller, more personal stories as well. Narratives of Nehru and Chandigarh, the model city, arrive in the same chapter as stories about such individuals as Charles Correa and Louis Kahn, and gigantic projects by the Indian Public Works Department system.

The book is divided into eight chapters:

1. Introduction

2. Rationalization: The Call to Order 1855-1900

3. Complicity and Contradiction in the Colonial Twilight: 1901-1947

4. Nation Building: Architecture in the Service of the Postcolonial State, 1947-1960s

5. Regionalism: Institution Building and the Modern Indian Elite, 1950s-1970s

6. Development and Dissent: The Critical Turn, 1960s – 1980s

7. Identity and Difference: The Cultural Turn, 1980s – 1990s

8. Toward the Non-Modern: Architecture and Global India since 1990

The early chapters are an embodiment of (and introduction to) colonial and post-colonial life, and the many ripples empire can send out into our economies and our societies. Middle and later chapters show a national identity emerging from the British colonial aesthetic, and the results are often thrilling. India has greatly impacted the mainstream of modern architecture, as well as having been influenced by it. Kahn and Le Corbusier realized arguably some of their finest designs in projects in India. What India has given back to international architectural style becomes clear in the later chapters of the book.

A fellow faculty member tells me to put away all note cards while writing. “You want to write only what comes from you,” he says. Re-hashing what other writers before you have said is pointless. Amazingly, this entire book is like that – you get the sense that the authors are not simply covering the territory, but that they know the designers and structures and events first-hand. This is good scholarship.

Here is a typical passage:

Mohandas Gandhi’s vision was seemingly much more pragmatic and conservative if not reactionary by comparison to Nehru’s. But the modern India that Gandhi envisioned, in which the holistic coherence of its traditional village communities would be sustained against the insidious forces of industrialization and the city, was in many ways the more radical proposition.

Now these are two sentences rich with ideas, as only an idea that has been internalized and considered can be. It’s the difference between instant tea mix and tea that has been steeped in hot water – the same idea is conveyed, but with much more depth and understanding.

You can also see in this passage how useful these ideas are. We run across a similar idea to Gandhi’s – the city is evil, the village is virtuous – in film noir, in modern urban planning (Robert Moses versus Jane Jacobs), sociology (“It takes a village”), and in Peter Jackson’s recent movie “Mortal Engines,” in which villainous cities roam the world, gobbling up innocent villages. A single lesson plan from this book will yield a wealth of ideas and writing options.

The Umaid Bhawan Palace in Jodhpur, built to the design of Henry Vaughn Lanchester between 1925 and 1950. A product of the colonial age, British design with a hint of Indian identity.

It is good to see that the authors include city and village design as well as structures, which are far easier to write about. The mention of Gandhi is not a casual one, since any discussion of design and architecture needs to include consideration of economic class.

We should probably acknowledge their editor at Reaktion Books, Vivian Constantinopoulos, since my experience tells me that a supportive editor is crucial on such an ambitious undertaking as this.

While the book is too dense to assign more than a chapter to undergraduates, any number of passages can provide a rich critical-thinking challenge, one that scaffolds easily: architecture is design, and design is everywhere.

A book like this and a topic like this are too good to leave for just a few scholars

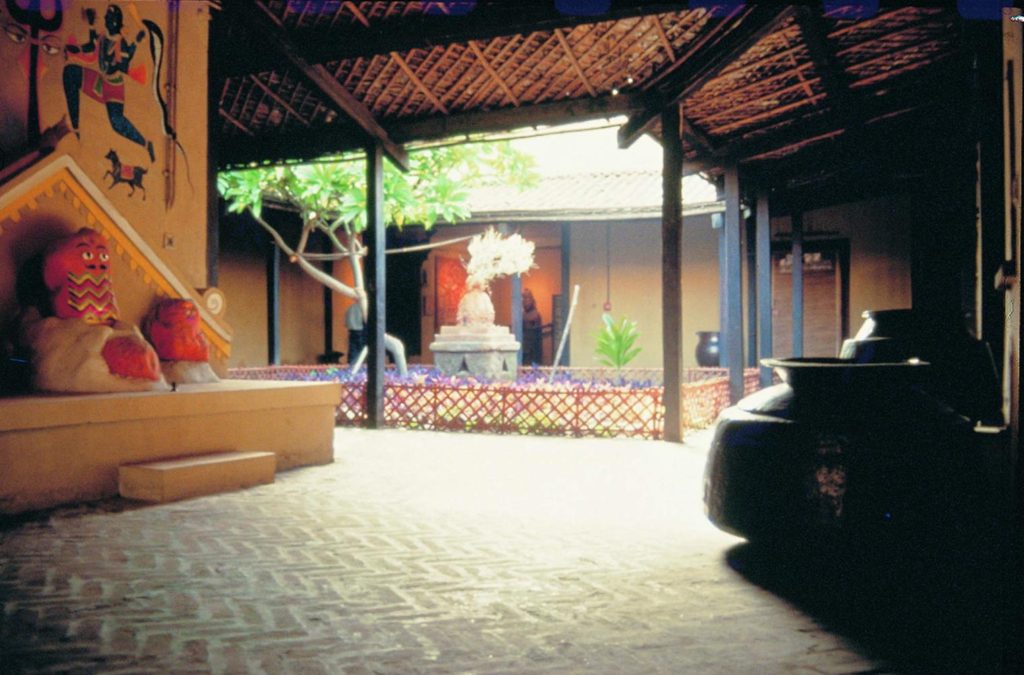

Charles Correa’s National Crafts Museum (1990) Towards an authentic Indian identity.

Interview with Amit Srivastava

and Peter Scriver

November, 2018

Literary critic Tabish Khair writes that there is a literature of “Babus,” the English-speaking, Brahminized classes, and a separate literature for “coolies,” or the non-English-speaking working classes. Is something similar true of Indian architecture?

In the case of any cultural product, architecture and literature alike, such a class influence is hard to transcend. But this distinction may not be so easily discernible for a casual observer. Let’s take the Oscar-winning film “Slumdog Millionaire,” where the desires and energy of an economically liberalised twenty-first century India are captured in an architectural allegory, from the gritty but vital intensity of Mumbai’s slums to the high-rise dream castles erected upon them.

____________________________________________________________

The lack of an established narrative might also give India an opportunity to leap-frog the self-referential form-focused trend in architectural design that currently plagues the West.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Despite the stark contrasts between them, both the slums and the towers – built to the designs of local celebrity architect, Hafeez Contractor – might be regarded as architectures of the “coolie” or salaried classes of today. In that fable a blue-collar ‘chai wallah’ can become a white-collar call-centre staffer. The respective architectures they inhabit merely reflect different stages of aspiration that resolve into the acquisition and display of material wealth. In 21st century India the (neo-colonial) “babu” class of the past could be equated with a minority of the economic elite who serve as patrons to a sort of aesthetically sensitive regional-cosmopolitan architecture that we have talked about in the book. Typically built for NGOs or other not-for-profit institutions, this architecture is more likely to respond to concerns of ecology and culture and be part of the global critical discourse. The distinction is thus not so much about financial capacity but about the circle of influence, and in a world dominated by social media this is the emerging new currency.

Is there an Indian aesthetic, or are the regional cultures too different from one another for a single style to dominate?

In our book, one of the themes we trace across the 150 years of history is the constant struggle between the centre and the regions, in both their colonial and their post-colonial definitions, to dominate the architectural discourse on style. At several points during this period the political centre employed architecture as a tool to consolidate the idea of India as a nation. The most obvious examples include the British establishment of New Delhi as the imperial capital in 1912, which allowed Edwin Lutyens to introduce a hybrid neo-classical style incorporating details from local architecture, and the establishment of Chandigarh under Le Corbusier immediately following independence in 1951, which legitimised bold modernist abstraction in steel-reinforced concrete as a solution to historicist inertia. But the regions proved hard to conquer, not merely because of the plurality of parallel religious world-views and caste and language-based sub-cultures that could not be adequately appeased. As outlined in the book, architecture remained part of the strategy of regional elites who actively worked to resist the political centre and developed international alliances to help develop their respective regions as global nodes in spite of the centre’s attempts at consolidation. So any attempts to establish a common Indian style were actively staved-off by the regional desires to defy

____________________________________________________________

One of the themes we trace across the 150 years of history is the constant struggle between the centre and the regions …

___________________________________________________________________________________________

political dominance of any kind, and it is this fact that makes India a fiercely democratic nation today. As a young man the late Charles Correa once queried (somewhat prophetically when we consider his later work): “Perhaps Indian architecture will be like Mozart– a great lyricism … the tree, the shadows, the texture, providing rhythm, and patterns, and counterpoint.” But, Correa was actually quite sceptical that there could ever be such a thing as a modern “Indian Architecture”, and certainly not a national style. He championed the autonomy of the independent practitioner to inform his or her own regionally, culturally, and individually distinctive approaches.

Crematorium, Ashwinkumar Ghat, on the banks of the River Tapti, Surat by Gurjit Singh (1996)

Name a worrisome trend in contemporary Indian architecture. Name a trend that you hope gains more traction.

As researchers and commentators the most worrisome trend in contemporary Indian architecture that we can discern is the lack of critical discourse. This is not so much about the lack of capacities for critical discourse but the absence of a consistent platform that has both the critical standing to ensure quality discussions and the capacity to inform the larger populace. In the book you will see that the decades following India’s independence were dominated by quality publications like Design Magazine and Marg, which had an advisory board composed of illustrious international names, and which included articles critically discussing architecture in relationship to the broader range of arts and design related activities in the nation.

____________________________________________________________

The decade long execution of the large-scale Indian projects by Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn also affected the construction industry …

___________________________________________________________________________________________

The editors of these publications were highly influential individuals that guided the national discourse on architecture. Even as these publications declined and newer market forces took over, the establishment of A+D in the 1980s provided a new platform for discussing issues pertinent to the profession. In the 21st century there are a handful of publications, events, and new media platforms (such as the website architexturez.net) that have attempted to address this lacuna but none have yet achieved the national standing that is required to allow the profession to move forward in an informed manner. A related concern is the alarming trend of new architecture schools being established, where the total number of these institutions has grown by about 150% in the last decade and the 400+ schools are capable of graduating as many students in a single year as existed in the country in total at the start of the century. In a country where the critical discourse is already lacking, the capacities of these new students to stay informed about important issues will be severely compromised. We hope that our book and the work we are doing with the architecture schools in India now will partially help address this issue. On the positive side, the lack of an established narrative might also give India an opportunity to leap-frog the self-referential form-focused trend in architectural design that currently plagues the West. The mindful establishment of a discourse based on socio-cultural and material realities of the nation, that is focused on the larger field of construction, and its early integration into the burgeoning education industry can give India an opportunity to truly emerge as a leader at a global scale. There are a handful of people that are involved in this process and we have the good fortune of working with them, so we hope this trend gains traction and that India can define a global discourse in architecture emerging from the realities of the Global South, which the world sorely needs right now.

You mention architectural “complicity” in the twilight of colonial rule. What elements or aspects of colonial style still carry over in Indian design today?

Similar to the previous discussion on the architecture of “babus” and “coolies,” the power of architecture as a cultural artefact to reflect social and political classes is undeniable. So, while we previously discussed this at a larger scale of the various social classes, it is equally true of individuals aiming to navigate their standing through the social or political hierarchy. In the context of the colonial era, as

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Good design must always, in some way, be a form of research into the social condition.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

discussed in the book, the administrative power associated with the official roles and titles were clearly reflected in the built plinth area of allocated housing, putting a measure of space and distance between the individuals as they climbed the social ladder. For the indigenous elite, then, architecture became an effective device to pursue assimilation, or to counter it, demonstrating architectural complicity or contradiction. Today this same spatial logic of the gazetted officer’s quarters and exclusive bungalow compounds of the colonial era is redeployed in the design and marketing of super-luxury apartment towers. Here the height, or the privately-secured lobbies and gardens, of the fortress-like podiums serve as the new distancing devices. In an increasingly liberalised and privatised economy, it is understandable that as young salaried individuals gain greater social status they aim to be part of one of these numerous gated communities that are popping up all over the country. It is sad to note, however, that following this trend the government has now chosen to replace the low-rise neighbourhood units of Delhi, arguably a more successful transposition of the colonial model by the PWD to provide for postcolonial government housing, by the far more generic typology of the gated high-rise.

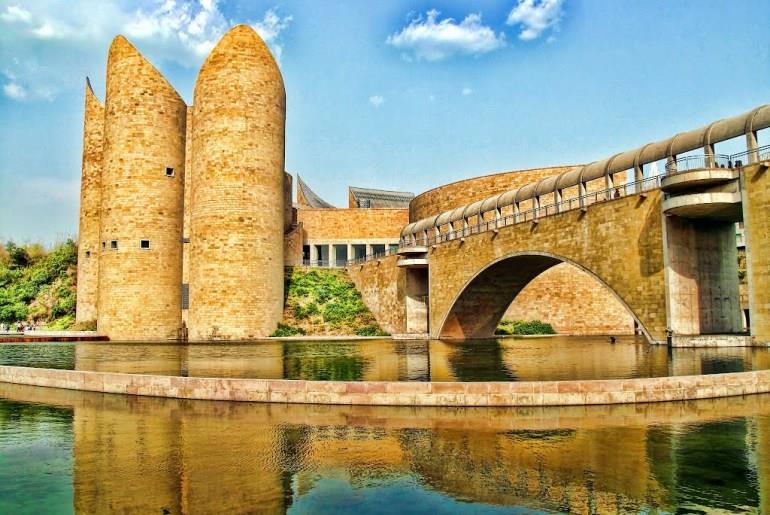

Virasat-e-Khalsa Museum, Punjab Province, Moshe Sofdie & Associates (1999)

What directions would you like to see in new scholarship in this field?

In discussing the issue of architectural discourse and architectural education in India we mentioned that India has the unique opportunity to avoid the pitfalls and problems facing architectural discourse in the West today, and one way of doing that is to move away from stylistic discussions of architectural form to focus on the larger field of construction. Existing scholarship on colonial and postcolonial issues in architecture continues to focus largely on architecturally conspicuous buildings and major infrastructure. While a minor number of researchers focus on routine production this is often explained through knowledge/power relationships within institutional forms of agency. By recognising the architectural profession as part of the larger political economy of construction we can develop a more robust understanding of architecture in the broader and bottom-up sense of the culture of building. Such an approach to the history and practice of architecture would focus on various parts of the design and construction process, not as a top-down or centre-periphery application but as an ongoing transfer and diffusion of building materials,

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Existing forms could be carried-forward, along with the cultural memory and knowledge that these embodied, and be re-composed or re-purposed for new functions.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

skills, techniques, as well as management processes and regulatory frameworks in which these are deployed. More scholarship in this direction, of what we may better call “construction studies,” will help develop a much bigger and more detailed picture of the architectures of the Global South, and of the realities in which these are produced; one that supersedes prevailing notions of a “techno-scientific culture” determined by the former colonisers.

Why did Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn have such a big influence on Indian architecture? What would they say about the progression of design if they were alive today?

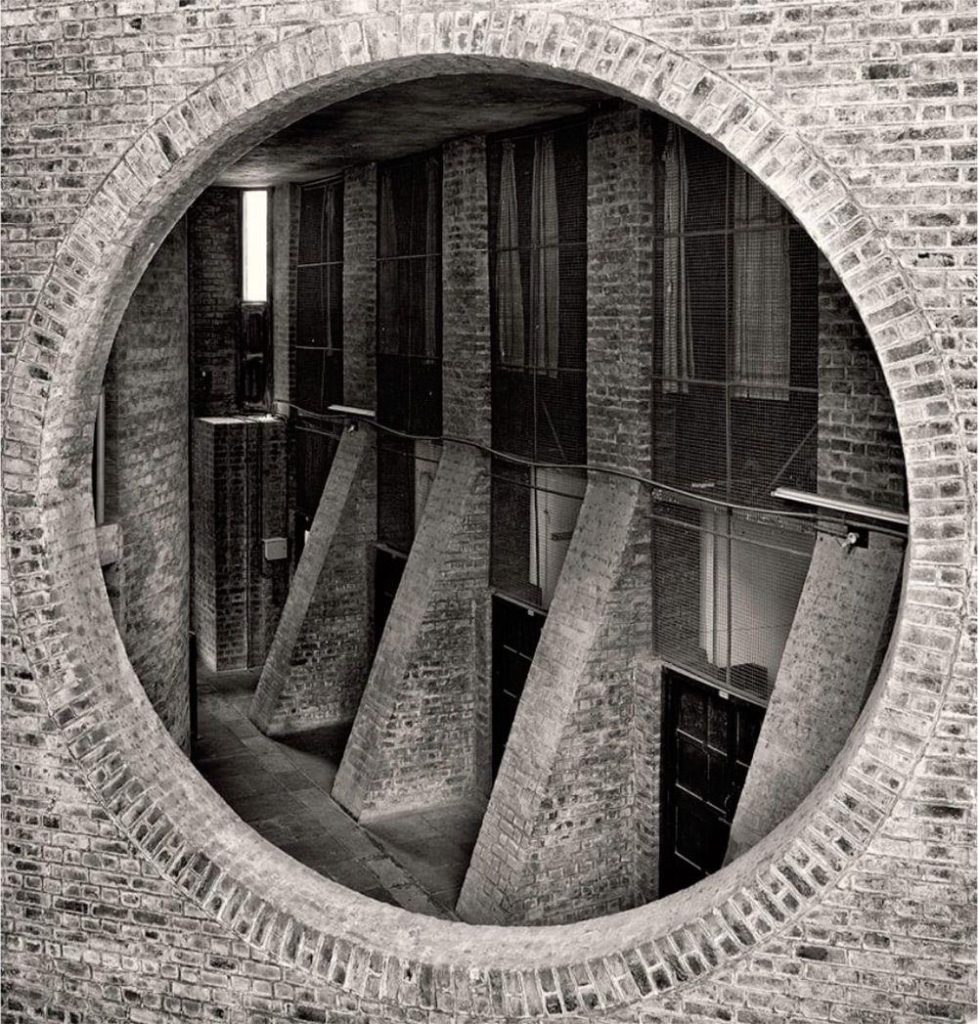

Both Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn arrived in India at an interesting time. In the decades following independence the leadership of India and its most influential regional elites were all looking to define a new direction for the nation, and Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn proved to be strong allies. But more significantly, the large-scale governmental and institutional projects undertaken by the two architects, constructed within the context of the resource limitations of the 1950s and 1960s, took a relatively long time to be realised. This extended involvement ensured that many younger Indian architects and trainees were inducted into their vocation through the experience of working on these projects. The direct, intense and prolonged collaboration that architects like Aditya Prakash, or Balkrishna Doshi, or Anant Raje, among many others, enjoyed with these celebrated international architects gave them confidence to embrace comparably large scale design commissions early in their own careers. Whilst some of these individuals were to become influential practitioners themselves, the formative mentorships of their early careers also inspired many of the same to become passionate architectural educators as well, informing the thinking of a whole new generation.

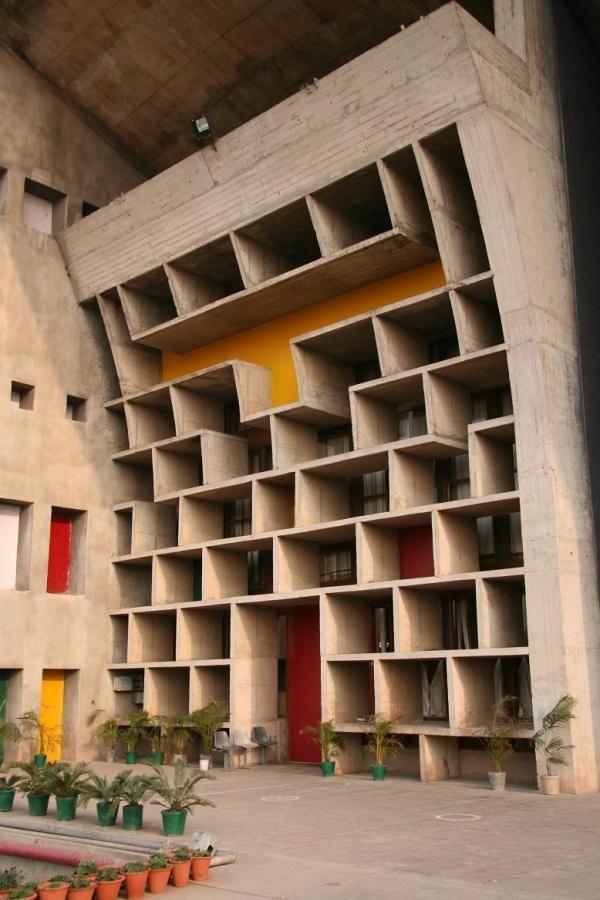

Le Corbusier’s Palace of Justice, Chandigarh (1953)

The decade long execution of the large-scale Indian projects by Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn also affected the construction industry, leading to changes in material production and distribution as well as the training of construction labour and contractors. In this more diffuse but profound way, therefore, this was to inform the design and construction of many subsequent buildings in the regional vicinity of the original projects. It is worth noting, however, that in spite of the generous representation of these ‘master’ works in architectural literature, the extent of the direct stylistic emulation of either Le Corbusier or Kahn in India was surprisingly limited beyond the immediate urban regions in north and western India in which they actually built. As for what their opinion of India’s subsequent design progression might be, if they could share that with us today, it is probably more interesting to consider the profound influence that this experience of building in India had on their own contemporary and subsequent work elsewhere, and how the teachings of their closest Indian associates continued to inform their architecture and, through it, that of the late modern world more broadly.

Louis Kahn, India School of Management (1962)

Can you suggest to the general reader, or student, what the concern is over good design. Why should they care about form and function?

+

Is it a legitimate worry in India that the best architecture is reserved for the wealthy? Does new architecture reach beyond museums, opera houses, and corporate offices?

Architecture is not merely an objective provision, and, as demonstrated through the book and in our discussion here, architectural design is deeply intertwined with the political, cultural, and economic fabric of society. But this connection can only be understood through a deeper consideration of the role of form and function. Too often, in architectural design, we encounter a fetishization of form for form’s sake, leading to the commodification of design as a mere luxury and a dispensable indulgence for the rich. The niche marketability of ‘starchitect’-designed buildings for the edification of a privileged few, in India and much of the rest of the world today, is a symptom of this disengagement with the spatial and material issues of the built environment. But let’s take the example of some of the first-generation architects practising in the domains of housing and human settlements in newly independent India between the 1950s and 1970s.

The modernist design doctrine of the day was ‘form follows function’ and innovative new design solutions were meant to arise from a rigorous investigation, starting from first principles, of the needs and purposes to be served. But these Indian architects tended to recognise that good design might also be premised on the reverse principle: that is, that existing forms could be carried-forward, along with the cultural memory and knowledge that these embodied, and be re-composed or re-purposed for new functions. This is a recurring observation in our book, demonstrable, for instance, in the conscious resonance between the new medium-density urban housing typologies that Kuldip Singh, Ranjit Sabhiki, and other architects were developing in Delhi in the late 1960s, and parallel teaching-based research into traditional Indian urban form and structure that was being conducted at the same time in the local schools of architecture. Elsewhere we discuss the notion of “jugaard,” or frugal engineering, in Indian design culture and practice, where problem-solving research and innovation – occasionally quite uncanny in its brilliance – may be compelled by resource limitations. Good design may entail good craft, but artful reproduction is not, in itself, good design. Good design must always, in some way, be a form of research into the social condition.

# # #