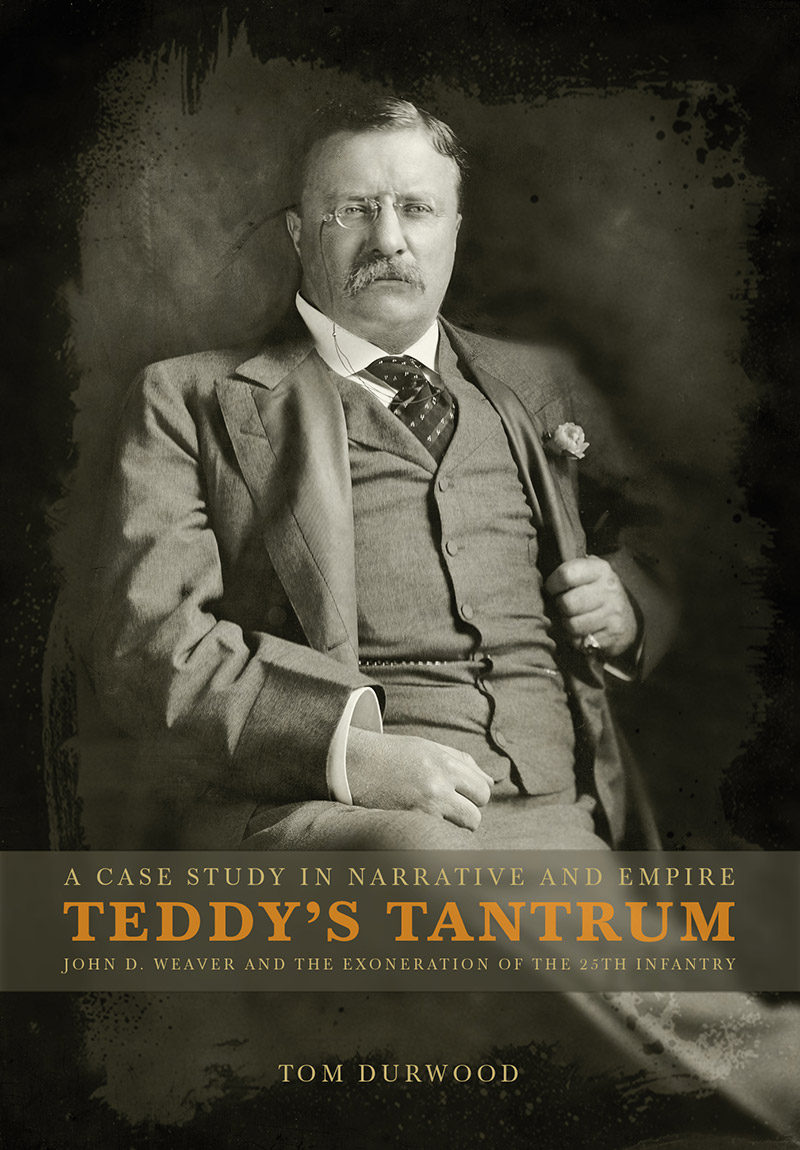

Teddy’s Tantrum

A CASE STUDY IN EMPIRE AND NARRATIVE

John D. Weaver and the Exoneration of the 25th Infantry

Editor’s Introduction

At a family gathering in 1967, a journeyman writer named John D. Weaver pointed to a photograph in the family album.

At a family gathering in 1967, a journeyman writer named John D. Weaver pointed to a photograph in the family album.

“Where was that taken?” Weaver asked his mother.

“Texas, dear,” answered John’s mother.

“And what were we doing in Texas, Mother?”

“Some Negro soldiers shot up the town,” she explained, “and Teddy Roosevelt kicked them out of the Army.”

Thus began the uncovering of one of the great “lost” stories of the 20th century, the story of Theodore Roosevelt’s epic 1906 temper tantrum. It was one of the worst moments of one of our best presidents, and a narrative that largely went untold for half a century.

His curiosity sparked by this stray remark, John Weaver investigated. His mother was entirely correct: President Theodore Roosevelt had issued Special Order 266 on November 9, 1906, dismissing without a trial 167 loyal soldiers of the all-black 25th Infantry. The men were suspected of making a midnight raid in the border town of Brownsville, Texas, yet the case against them was unproven. What is more, Weaver found that Roosevelt carried out a vendetta against the troops of the 25th Infantry, hiring private investigators to coerce “confessions” and to gather the flimsiest evidence against them. Roosevelt then drummed their champion, Senator Joseph Foraker of Ohio, out of office. The popular Roosevelt suffered no political consequences to his epic temper tantrum, and the men of the 25th Infantry were lost to history.

The Brownsville episode arose when Roosevelt, in a fit of rage, ordered the dishonorable discharge of several units of Negro troops …

With the support of his wife, Harriett, John D. Weaver spent three years digging up the entire buried episode. He retraced the streets of Brownsville, and measured the alleyways where witnesses claimed they saw the troops shooting. He found the case against them suspiciously weak. In 1970, he published a book about the Brownsville Raid which exonerated the soldiers. In February of 1973, the U.S. Army issued an apology to the men of the 25 Infantry and awarded the sole surviving battalion member (Dorsie Willis) back pay. Historian Lewis Gould called Weaver’s work a correction of “one of the most glaring miscarriages of justice in American history.” It was a victory of a true narrative over a false one.

Now a new ebook written by Tom Durwood, Teddy’s Tantrum: John D. Weaver and the Exoneration of the 25th Infantry, takes a look at this “lost” episode and the lessons it holds for us. Weaver’s detective work dredging up the true contours of the Raid were remarkable; equally remarkable is the fact that it took so long for the true story to emerge as part of the public record. Durwood finds in the episode several themes regarding the workings of empire, and the relationship between literature and empire. As one culture colonizes another, so does that culture’s literature “colonize” such narratives; only the imperial version survives.

The rising American empire, Durwood theorizes, played a large part I the fate of the 25th Infantry. Roosevelt’s intense desire to lead America onto the world stage helped drive him to so abruptly, and wrongly, dismiss the black troops, who could scarcely fight back. The Nobel Prize which Roosevelt won for brokering peace in the Sino-Soviet War and his daring success with the Panama Canal represented the prizes TR sought; disloyal Negro troops represented an obstacle. The fact that he had charged San Juan Hill with some of the very men he was dismissing fell to the wayside.

Historian Lewis Gould called it a correction of “one of the most glaring miscarriages of justice in American history.”

Black newspapers of the day decried the miscarriage of justice. Benjamin J. Davis, editor of the Atlanta Independent, put it plainly, comparing Roosevelt to two notorious racists: “The hand of Ben Tillman nor Vardaman never struck humanity as savagely as did the iron hand of Theodore Roosevelt. His new dictum is lynch-law, bold and heartless.” Such were the dynamics of empire that African American journalists did not have the standing to impact the Brownsville “verdict.” It would take a white reporter (Weaver) to write a version that would attract Congressional attention and bring about an official apology in 1973. By that time, the empire needed to repair the Brownsville trauma, since America’s black soldiers played a key role in the Vietnam War.

Teddy’s Tantrum is a chronicle of the overarching Brownsville story, treating Weaver’s work and the troops’ exoneration as equal parts of the narrative. Original scholarship provides an account of John D. Weaver’s early career and his two-decade campaign on behalf of the 25th. In the manuscript’s first sections, the author follows three separate storylines – John Weaver, Theodore Roosevelt, and the men of the 25th Infantry – until the three merge, and Weaver’s detective work uncovers the truth of the buried episode. In the book’s third section, the author looks at the work of seven scholars to help interpret the many aspects, roots and consequences of Special Order 266. Teddy’s Tantrum closes with the author attending the Brownsville Centennial in 2006, where the last word belongs to a Texas Congressman:

John Weaver’s book, “The Brownsville Raid,” is displayed in a glass case in the reception hall, its red cover bright and visible. Planted in the sunny courtyard lawn outside, 167 small flags fly, one for each of the dismissed soldiers. Handsome full-color invitations and at least a dozen articles in the Brownsville Herald have anticipated today’s event.

Congressman Solomon Ortiz is the main speaker. An Army veteran, he is a member of the House Armed Forces Committee.

“Today, we take a hard look at our past,” he tells the crowd.

“The only way we can overcome the uglier incidents in our history is to face them.”

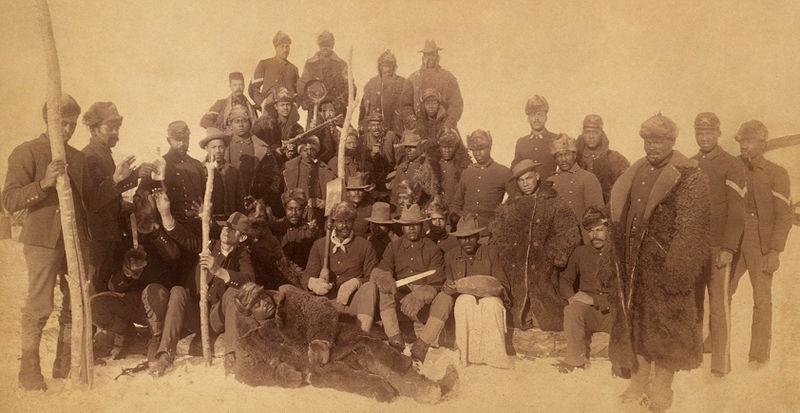

Buffalo Soldiers of the 25th Infantry Regiment, 1890

Wikimedia Commons

The Tantrum and Its Aftermath

Theodore Roosevelt’s epic 1906 outburst turned into a national drama that would last over four years and ruin over a hundred lives, generating tens of thousands of words of controversy in newspapers, in Congress, and in churches and communities across America. It ended the political career of the Senator who opposed Roosevelt, who compounded the tantrum by refusing to make amends, going to extraordinary ends to avoid doing so. Yet the true Brownsville story was quickly buried by the myth of “TR,” and remained so until John Weaver uncovered it.

In February of 1973, the U.S. Army issued an apology to the men of the 25th Infantry.

“The Brownsville episode arose when Roosevelt had, in a fit of rage, ordered the dishonorable discharge of several units of Negro troops …” writes Taft biographer Judith Icke Anderson. The Brownsville Raid was known to Roosevelt historians before John D. Weaver took up his crusade, but it was unknown to the general public.

In his account of the original episode, the “burial” of the 25th Infantry from American history, and their eventual resurrection, Durwood begins with John D. Weaver. The first section of Teddy’s Tantrum traces Weaver’s career as a journeyman writer. One of his early influences was the 1932 Bonus March in Washington, when U.S. Army veterans protested on Capitol grounds for fair compensation. “John loved standing up for things he believed in,” said his friend and editor, Pamela Fiore. His principles came at a cost.

In Weaver’s correspondence with his friend John Cheever lie clues to his struggles. His work was not as popular as his friend’s. Here is Weaver’s note to his agent in 1956, discussing his reluctance to undertake books:

“As you know, I have no outside income. I depend entirely on my earnings from writing and, for the last three years, I have not been able to make a living from the magazines. And when I think of doing a book I remember the year I spent on “Another Such Victory” and the $1,000 advance I received, and never another red cent.”

It does not take much imagination to conjure up the trepidation he must have felt when embarking on the research for the Brownsville book.

The second section of Teddy’s Tantrum traces Weaver’s detective work, as he discovers variance between the official record and events as they truly occurred. Durwood presents Weaver as a traditional American hero, a lone warrior fighting against odds to bring about justice:

In tracking down the original story, Weaver is demonstrating the American method of resolution: this is how we work through psychological knots, with patience, hard work, logical argument, passionate commitment, simmering outrage, and a little sarcasm. Weaver, the former Kansas City Star journalist, displays a reporter’s ability to track down disparate sources and present them as parts of an integrated whole.

Perhaps the incident’s final and greatest meaning has come through John’s own detective work. It is Weaver who narrativizes this fragmented tale, pulling the disparate, disjointed and distorted pieces together. He took the time to go through the Congressional record. He took the trouble to travel to Texas and stand in the alleyways. He found copies of fifty-year-old newspapers in small towns in Georgia and Nebraska.

Weaver’s book attacked the accepted version at all points…

The ebook’s third section offers readers an array of explanations, not only for the original Raid but for the disappearance of the episode form the public record. The author looks to a range of sources for analysis that can shed light on the fate of the 25th Infantry. One notable such scholar is the literary theorist Edward Said. Published in 1972 (almost concurrent with Weaver’s book, The Brownsville Raid), Edward Said’s Orientalism introduced the idea that a dominant culture captures and dominates its conquered cultures in its language and its images. So the West captures the East (“Oriental” in this case includes all Asian and African cultures) in language, portraying it in terms the Western mind finds acceptable. Western narratives gobble up Eastern narratives; any empire defines the colonized in whatever terms suits it – The British, for example, portrayed the “Others” of Arabic culture so vividly in The Arabian Nights that those images still linger today, an epoch later. In the Brownsville case, the Others were the men of the 25th Infantry.

Another avenue to explain the tantrum is Roosevelt’s personal psychology. A sickly boy (who was often dressed in frilly clothing) whose father had hired others to fight for him in the Civil War, Theodore Roosevelt became obsessed with masculinity; after his first wife’s death, young TR reinvented himself as a cowboy, boxer, and hunter. Durwood points to Roosevelt’s complex personality as a source of the Tantrum:

Roosevelt took pride in his temper, since it reflected a properly “savage” heart. Roosevelt spent his lifetime keeping his temper in check. “I keep my good health by having a very bad temper, kept under good control,” he was fond of saying, and if any of his listeners thought he was making a pleasant aphorism, they were mistaken. It was a very, very bad temper.

The author also cites Roosevelt’s global war on native people as a pillar of Special Order 266, as well as his powerful sense that all hell was about to break loose:

“We stand at Armageddon,” Roosevelt would say, or “We are fighting in the quarrel of civilization against barbarism, of liberty against tyranny,” or “I believe that the next half century will determine if we will advance the cause of Christian civilization or revert to the horrors of brutal paganism.”

He warned repeatedly of “the general smash-up of our civilization” and the “endless crusade against wrong … the never-ending warfare for the good of humankind.” None of this was mere rhetoric, but rather reflected a passionate conviction. His apocalyptic foreshadowing cropped up in all facets and at all junctures of his life.

The seemingly snap decision to dismiss the men of the 25th had deep roots in TR’s world view. “All the great masterful races,” wrote Roosevelt, “have been fighting races, and the minute that a race loses the hard fighting virtues it has lost its proud right to stand as the equal to the best.” Theodore Roosevelt sought through breeding and vigorous exercise to build up the white race. But it was not for any kind of exultation, rather for the comprehensive and deadly serious task of saving the rest of civilization. “If we refrain from doing our part of the world’s work,” wrote Roosevelt, other races will not, and “we will have shown ourselves to be weaklings.”

Teddy’s Tantrum also gives glimpses of the powerful tributary story, the rise to honor of black soldiers through the wars of the 20th century. Among the supporting cast are Colin Powell and Jalester Lincoln, last of the Buffalo Soldiers.

The epilogue of Teddy’s Tantrum closes the Brownsville epic with the author attending the Raid’s Centennial anniversary. In the end, the ebook concludes, Weaver’s difficulty in dislodging the official version stems from his doing battle with two hugely powerful foes: the myth of TR; and our idea of ourselves.

Author Interview

Interview with “Teddy’s Tantrum” author Tom Durwood, December 2017

Why did you write this ebook?

I took a course in Trauma and Literature in my Masters program and learned how narratives can correct the past, and help make us collectively whole. I had run across the story of how John D. Weaver rescued the and felt it was a perfect example of this. What Weaver did was remarkable, and he was entirely alone in it. I wanted to get him some credit. I also feel that this is case study that shows how all narratives can be influenced by where they stand in the rise and fall of empires.

What were the challenges you faced in writing this ebook?

I came across such a rich cast of supporting characters — Belle Green, Walter White, William Howard Taft, John Cheever — that I had to skim over them or leave out them out altogether, for fear of diluting the main story, the Weaver story.

One drawback to my ebook is the absence of the men of the 25th Infantry. I wanted very much to show the full thread, to show the full impact the dismissal had on them, and their descendants, but I could not pick up their trail.

Weaver found that Roosevelt had carried out a vendetta against the troops of the 25th Infantry…

Was Roosevelt evil? Does this make him a bad president, or a bad man?

No, I don’t think he was evil, but he did behave terribly in this case. An important point that John D. Weaver made was that this was not an isolated tantrum at all, but a sustained and deliberate persecution of innocent men.

Roosevelt knew that black soldiers’ narrative did not stand a chance against his own. His blueprint for “disappearing” the Brownsville troops from history is given clearly in his essay “History as Literature,” he clearly spells out that rules: it is the vivid, heroic histories that always win over readers. His own story was a juggernaut compared to that of his antagonists.

Roosevelt was also canny enough to understand that the Congress was remarkably weak at the moment of his presidency: “I do as I see fit, and let the rules catch up,” he often said.

What does empire have to do with Special Order 266?

One of my early readers, Prof. John David Smith of The University of North Carolina Charlotte, suggested that this was a story about empire. I followed that lead. What I found convinced me to broaden the scope of my ebook, to include the Battle of Tsushima, J.P. Morgan and the New York trusts, and especially the Panama Canal. Roosevelt bet heavily on the canal, where ten thousand black men with dynamite worked to build his legacy. It gave him a special interest in dealing swiftly with a revolt by black soldiers on the Texas border.

Are there other “lost” stories out there?

Many! In 1932, an historian named Tyler Dennett found a telegram suggesting that the famous Perdicaris incident that had so burnished TR’s reputation had been had been greatly exaggerated. Roosevelt as a careful manager of his own myth.

In 2001, a Panamanian author named Ovidio Diaz Espino published a book, How Wall Street Created a Nation, that tells the full story of how Roosevelt masterminded the swindling of the Panama Canal away from Colombia.

In 1973, a San Francisco woman named Solace Wales was vacationing in an Italian town, Sommocolonia, when she came across a stone marker in honor of the segregated 92nd Infantry Division. She eventually uncovered the amazing story of Lieutenant John Fox.

I’m sure there are many more —