Polar Bears and the Real Arctic

ROUGH DRAFT

Phillip Pullman, Polar Bears and the Real Arctic

R.L. Shields

How a Close Reading of History Matters to “His Dark Materials”

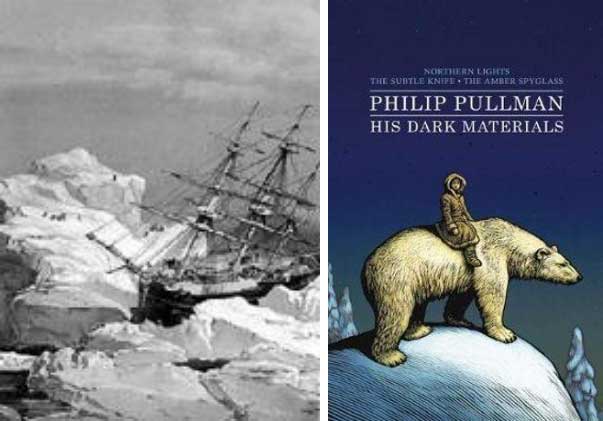

Explorer Robert McClure’s The Investigator was trapped in ice throughout 1852. Authors like Phillip Pullman often use real-life episodes such as this one as the basis for his fiction.

Editor’s Introduction

“Children’s literature should be subjected to critical rigour as much as grown-up writing … Children’s literature occupies a very different position from literature as a whole, largely because of two things: it’s part of nurturing, in the anthropological sense, but it’s also part of education.”

– Children’s Laureate Michael Rosen

“Fantasy stories that are based on human history, even when significantly altering it, present certain challenges,” writes R.L. Shields in her essay (below). The scholar takes the Phillip Pullman series “His Dark Materials” and “The Golden Compass” in particular as a case in point. In her close examination of the work, she reveals larger considerations.

“His Dark Materials” is a most ambitious epic trilogy (with two shorter books set in the same universe) with a large cast of characters, set in a complex fantasy world, depicted in the ambitious 2019 television series created by BBC and HBO.

The story’s 11-year-old heroine, Lyra, travels through parallel worlds with a daemon and a truth-telling alethiometer (or ‘golden compass’). All humans have a daemon and they represent a part of their personality, like alter-egos. Aided by armored polar bears called ‘panserbjørne’ (who may well be stand-ins for the Inuits), Lyra and her companions must deal with the mysterious Magisterium described as “a version of the Catholic Church that never ceded its power over Europe.” His Dark Materials represents a significant achievement in modern young-adult fiction. “It breaks away dramatically from the tropes established by some of the giants of fantasy literature before Pullman,” says Dr Dimitra Fimi, lecturer in Fantasy and Children’s Literature at the University of Glasgow.

In this essay, scholar R. L. Shields looks at Pullman’s fictional world to demonstrate that how we view the past can sometimes be through a lens that is warped. For example, the snow-bound sequences of “The Golden Compass” are based on historical accounts of Arctic explorers Martin Frobisher and Henry Hudson. Yet, she cautions, there are challenges in this re-telling of history:

Phillip Pullman draws heavily on the British history of polar exploration as Victorians imagined or hoped it to be; his explorers are heroic, manly men who shape the landscape to their own will and beautiful women in impractical clothing who never look worse for wear. For the most part, references to cannibalism, scurvy, and other real indignities of Artic exploration are left out of his version. There is little reference to frustrations and setbacks …

Next, she considers the role of ‘sensitivity readers,’ early readers who are meant to help fiction writers depict characters different from themselves carefully and considerately.

R.L. Shields uses these stepping stones to ask two larger questions:

1) Do we romance the past in the choice to resurrect it?

2) How does one balance nostalgia for some aspects of a historical period without seeming to approve of all?

These are questions we can apply with similar impact to epic fantasies like “Harry Potter,” with its many echoes of the British Empire, and “Dune,” a science-fiction work based on a feudal society in which noble houses control planetary fiefs. Closely tied to this consideration of romanticizing the past is our view of other civilizations, and how it has changed. Edward Said’s concept of ‘Orientalism,’ of one culture can seek to capture another through narrative and art, is certainly a part of the discussion.

Shields ends her excellent essay with a warning for readers: “As Sampson writes, “Our responsibility as literary critics, however, is not to let the shadows of imperialism go unchallenged, even in acclaimed works of literature.””

The wide-ranging interview which accompanies the article ropes in works from “Game of Thrones” to “Tripods” and authors from Zadie Smith to the poet Rick Barot in order to provide readers valuable context for “His Dark Materials.”

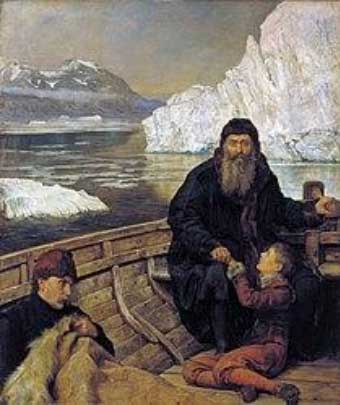

John Collier’s painting of the arctic explorer Henry Hudson, his son, and loyal crew set adrift.

Interview with R.L. Shields

September, 2019

1) What is a ‘sensitivity reader’? Why are they needed now?

What would Mark Twain or Charles Dickens or Harper Lee think of them? What would a sensitivity reader think of these authors and their work?

I have an M.F.A. in creative writing and there is intense debate within that field related to representation and identity. Are we allowed to write outside our own experiences? Sensitivity readers are meant to help fiction writers depict characters who are different from themselves carefully and considerately. Usually, the sensitively reader shares aspects of identity with the character and can give writing advice based on lived experience.

A few years ago, I attended a lecture by the poet Rick Barot (https://rickbarot.com/) during which he told the story of a student of his (a woman of European descent) who wanted to write poems from the perspectives of Japanese people who had been held at Manzanar during World War II. His first reaction was to tell her stay away from this idea, but then he changed his mind and told her she could try it, but she needed to research the subject so thoroughly that no one would be able to say that she had been disrespectful. I think I agree with his advice. The answer is not to give up on writing outside your experience, but to always put your best effort into writing with care (perhaps with the help of a sensitivity reader). When it comes to something like Manzanar, it seems wrong to discourage conversation, even if the person bringing this historical moment to light is not the messenger you envisioned.

Author Francine Prose has an article (https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2017/11/01/the-problem-with-problematic/) about sensitivity readers in which she defends some of the authors you mention above. She thinks that the imaginative work of fiction is essential, as I also suggest in my article. Her focus, however, is on how imagining the lives of our contemporaries—even if our imagining is not always flawless from the perspective of a sensitivity reader—helps us to emphasize with them and solve the problems of our current moment. Twain, Dickens, and Lee all critiqued the societies they lived within and used their stories to connect people across difference in order to build empathy and inspire social change.

2) Why should students care what lies beneath the surface of books and movies they enjoy?

Do these same ideas apply to the stories which students themselves tell?

The reason I think people should carefully examine the stories they love starts with my own childhood reading experiences. I remember thinking, when I was probably around ten years old, that it was too bad that there was only one kind of girl hero—most of the girls I read about seemed as if they were nearly the same person (red hair, fierce, good at traditionally boyish things), whereas the boys I read about could be heroic in all kinds of different ways. Some were shy, some were bold. Some fought with their hands, others with their words.

For example, I loved the Tripods books (by John Christopher) and they feature a trio of boys with very different abilities and traits who help each other escape from alien colonizers. I remember thinking that real-life girls must not be as interesting and complex as boys, or else there would be a larger variety of girls in books. This seems like a really bizarre conclusion to me now, but there were fewer children’s books with female protagonists then. Needless to say, I’d much rather students learn to critique an author’s choices than come to a conclusion like this one!

I differ a bit from some people, however, in that I think that critiquing a book does not mean that you have to stop liking it. I love many books that I also find offensive.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Most of the girls I read about seemed as if they were nearly the same person (red hair, fierce, good at traditionally boyish things), whereas the boys … could be heroic in all kinds of different ways.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

And yes, the narratives we create do matter and we should think about how we tell our own stories. If my English-major perspective is not convincing, this recent article in the Washington Post explains how essential storytelling is for economists (and the public they are trying to speak to): https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/10/19/worlds-top-economists-just-made-case-why-we-still-need-english-majors/

3) You write:

In some cases, there is an obvious pedagogical function of a return to the past—to emphasize how inhumane slavery is, or the unfairness of barring women from education—but, in many others, there seems to be at least some romancing of the past in the choice to resurrect it.

What other literary properties “romance the past in the choice to resurrect it?”

Some of the most obvious examples of romancing the past appear in television shows or movies (many of them based on books) and Game of Thrones comes to mind right away. I’m going to get in trouble here because many people love the show (and/or the books), but I’ve had this issue with the story from the start: since this is clearly a fantastical version of the middle ages, why must it be dominated by white men? If you’re going to invent ice zombies, why not gender equality as well? And, if we’re really going to be historically accurate, why not take the model of medieval Iceland, where women mostly ran the farmsteads on their own and could sue for divorce?

________________________________________________________________________________________

If you’re going to invent ice zombies, why not gender equality as well?

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Yes, there is a long list of exceptions to what I’ve just said about the series, though part of my problem is that they all seem like exceptions rather than the norm. Specifically, nearly all of the women in positions of power are one-of-a-kind. Brienne of Tarth is the only female knight we know of and Arya Stark seems to be fairly unique among assassins. Melisandre is a lonely priestess. Cersei Lannister, Daenerys Targaryen, and Sansa Stark only rise to positions of leadership after suffering years of abuse and powerlessness. Two of them are, arguably, made insane by their growing power (which does not seem to be an issue for the majority of men). Only one of them retains her position. Note, as well, that all of the women I have listed are not people of color (of the two most prominent women in this category, Missandei could possibly be called the power behind one of these thrones, but Ellaria Sand’s storyline drops out of sight in the television series). In stories like this one, which is predominantly for the purpose of entertainment, I worry about what we find entertaining and how this scenario might speak to a nostalgia for a time when women had fewer legal rights and only a few exceptional women had power to direct their own lives.

Also, after the humid Missouri summer, I’m ready to join the Night’s Watch and patrol the frozen north, so I hope they start recruiting women. Is winter coming soon?

Still from HBO’s “Game of Thrones,” another epic confronting romance of the past.

4) Some English teachers (like me) tell their students that every poem, every story, every work of literature has an apparentconflict and a discovered one.

Does that apply to “The Golden Compass”? Does the reader discover an opposition that is completely different than the one we started with?

It would be difficult to pick just one apparent and one discovered conflict! Without giving away too much of the story of His Dark Materials, it’s clear that questioning authority is a major apparent conflict. Various readers and critics have discovered conflicts between this clear message about disobeying authority and fighting for knowledge and some underlying ways in which the story actually upholds and reinforces particular types of authority and knowledge.

5) Edward Said suggests that almost every work of literature is, in its own way, political. Every poem, every play, every story sets forth a certain philosophy of the world in which there is a hierarchy; it can be used to further one nation or one culture over another.

Is “The Golden Compass” political? Is it a British story, seeking to culturally dominate another culture? How would it be different if it were written by a Japanese author, or an African author?

Yes, in a general sense, I think that The Golden Compass is definitely political. Pullman is saying that we should question authority, but he also might be implying, perhaps unintentionally, that certain elements of Britishness make Lyra particularly good at resisting and defying those in power. There are other characters who perform heroic acts and resist authority as well, so this is not true in every instance throughout the series.

It’s hard to tell what these books would be like coming from a different perspective. I just saw Tarell Alvin McCraney’s play The Brothers Size at the Steppenwolf Theater in Chicago. McCraney uses Yoruba myth and other techniques to tell a story about young men who have just been released from an American prison. In the play, it feels like McCraney is telling us that he needs to borrow another kind of imagining to explain how things are in the U.S. In a sense, he’s saying that American mythologies are insufficient—that, instead of dominating the conversation, they need help, or even sometimes to be dominated by other stories.

6) You write:

How does one balance nostalgia for some aspects of a historical period without seeming to approve of all?

What is the answer? Can young readers enjoy “The Jungle Book” while at the same time disapproving of Kipling’s jingoism?

Benjamin Jean Joseph Constant’s “Arabian Nights” (circa 1899). An example of Orientalist art, a romanticized view of the East through Western eyes.

I’d like to answer this question by mentioning two current authors who I think do this well. Zadie Smith and Kazuo Ishiguro write with, against, and outside of the British literary tradition, often switching modes many times within one novel. Smith was born in the U.K. and has one Jamaican parent, and Ishiguro was born in Japan, but has lived in the U.K. for nearly all of his life. In both cases, it is very evident that they love some of the English literature that preceded their own, but also that they’re very capable of inventing unique stories and techniques. Smith, particularly in White Teeth, creates a modern version of the panoramic novel that Charles Dickens and other earlier novelists pioneered. Ishiguro reimagines everything from Arthurian legends to Sherlock Holmes. Their interactions with the literary past are far too complex to describe here, so I highly recommend reading their work to see how it unfolds.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

American mythologies are insufficient … instead of dominating the conversation, they need help, or even sometimes to be dominated by other stories.

________________________________________________________________________________________

7) You end your essay with a warning for your readers:

As Sampson writes, “Our responsibility as literary critics, however, is not to let the shadows of imperialism go unchallenged, even in acclaimed works of literature”

Can you point out ‘shadows of imperialism’ in other recent films? The Avengers? The Black Panther?

I am a bit scared to weigh in on the Black Panther debate because it is so complicated, but I’ll try. Many people applaud the way in which the film depicts an African society that has remained powerful and untouched by European colonialism. Many people argue that this kingdom (emphasis on “king”) is too politically conservative in its structure and ideals. I can see the reasoning of both sides (and there are quite a few people who land somewhere in the middle of this debate, or somewhere else entirely, of course).

In the context of these reactions, the main thing that struck me when I was watching the film is that the story seems to go out of its way to undermine Erik Killmonger (played by Michael B. Jordan). Killmonger argues that the kingdom of Wakanda should use its superior technology to support a worldwide revolution of oppressed people. His viewpoints on reversing colonization might seem more reasonable if they weren’t so bloody—if he wasn’t named Killmonger and otherwise shown to be violent and power-seeking. I thought this choice of characterization showed some hesitance on the part of the filmmakers to seriously engage with a radical political discussions, or even just incorporate a more complex range of ideas within our current conversations about racism and reparation.

Pullman’s work deals with religion and power in the religious organization The Magisterium. Photo of Pope Francis: National Catholic Reporter.

ESSAY

Imaginary Limits: A Cold-Sensitive Reading of Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass

R.L. Shields

Philip Pullman’s series of young adult books, His Dark Materials, features an alternative reality to our own in which much of Europe is ruled by a theocracy and the imagination of Victorian England has written itself upon reality. For instance, the accounts of Arctic explorers from the late 1500s to early 1600s, such as Martin Frobisher and Henry Hudson, which inspired the Victorian’s own explorative efforts, are taken to be more literally factual than we now know them to be today; the Arctic is, indeed, a place of mystical metallurgy and portals to other worlds. Frobisher’s mineral finds are not evidence of gold, as he hoped them to be, or iron pyrite, as they in fact were, but something even better, a “sky metal” used by anthropomorphized polar bears to create insurmountable armor. The disputed cartographies of both explorers (and those who followed them), in combination with theories about the nature of the North Pole—ranging from an open sea to a mythical utopian island—are, in His Dark Materials, extended into another dimension of time and space. Queen Elizabeth’s name for Baffin Island, Meta Incognita, generally translated as “unknown limit / boundary” or “value unknown,” (Loomis 99) proves an apt description of Pullman’s Arctic.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. As late as the 1850s, respected explorers continued to make mistaken reports of sighting new lands in Artic. In one instance, Captain Kellet, quoted in George Tyson’s Arctic Experiences, states, “It becomes a nervous thing to report a discovery of land in these regions without actually landing on it” before explaining how certain he is to have sighted “an extensive land”—he was wrong (Tyson 23).

Fantasy stories that are based on human history, even when significantly altering it, present certain challenges, especially when many characteristics of the societies they depict are problematic for modern readers. How does one balance nostalgia for some aspects of a historical period without seeming to approve of all? How does one choose which “rules” of the referenced time to follow; does one depict unequal gender roles, class distinctions, etc. even though there is no requirement in a work of fiction that those be maintained? In some cases, there is an obvious pedagogical function of a return to the past—to emphasize how inhumane slavery is, or the unfairness of barring women from education—but, in many others, there seems to be at least some romancing of the past in the choice to resurrect it.

In contemporary children’s literature, with the help of sensitivity readers and other kinds of editors, it has become less likely that authors will write overtly sexist or racist or otherwise problematic statements in a traditionally published book (at least not anything that can be linked to the author’s actual opinions and beliefs—there may be “bad” characters who say and do these things). Sensitivity readers provide authors with advice on how best to represent characters from outside their own experience. Usually, the sensitivity reader matches the character, at least in some ways and can speak from a position of experience. For example, an African American writer telling a story about an immigrant from Mexico might be paired with a sensitivity reader who is herself Latinx and can provide suggestions on how to accurately depict that cultural experience. Author Anna Hecker, in her defense of sensitivity readers, states, “rather than censoring my book, my sensitivity readers made it objectively better. By pointing out places where I’d unwittingly succumbed to stereotypes, they helped me create richer, more nuanced characters.” Beyond excising stereotypes and offensive remarks, sensitivity readers also work to reduce problematic power structures within fiction; for example, a story in which a light-skinned character rescues dark-skinned ones from slavery, replicating a “white savoir” narrative and implying that characters of color are somehow destined for an inferior role in society and in need of a warrior, or scholar, or princess from an elite race to protect or lead them to freedom. However, solutions to these structural problems are often only skin-deep. The author reverses the races of the characters, but the underlying structures, specifically the relationship between the peoples, remains in the book and may undergo very little change. Though it is, of course, very important to know and understand history, and to process it in various forms (including within fiction) it is sometimes disturbing how little we are able to imagine something else. If we cannot conceive of other kinds of relationships between human beings, how will we inhabit them?

As previously mentioned, Phillip Pullman draws heavily on the British history of polar exploration as Victorians imagined or hoped it to be; his explorers are heroic, manly men who shape the landscape to their own will and beautiful women in impractical clothing who never look worse for wear. For the most part, references to cannibalism, scurvy, and other real indignities of Artic exploration are left out of his version. There is little reference to frustrations and setbacks, such as the time that William Parry, during his search for the Northwest Passage in the early 1800s, realized that his team’s attempts to travel northward across sea ice had been thwarted because “The ice was moving beneath them, carrying them south with every hour” (Tyson 45). In Pullman’s alternative reality, Lord Asriel, like the infamous man in the white suit in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, has somehow managed to make a comfortable, culturally-specific home in this otherwise inhospitable-to-him landscape. In his discussion of imperialism in The Golden Compass, Corey Sampson states, “Pullman partakes of the same nostalgia for empire that [Edward] Said warns us about—even without explicitly authoring the British Empire into his work” (50). Not directly mentioning the British Empire is one of the ways in which Pullman (like many other authors of young adult books) tries to free his work from accusations of endorsement without really changing the power structures within his chosen era.

Depiction of the panserbjørne. (New Line Cinema)

More significant to the conversation on sensitivity than Pullman’s glamorization of exploration, as Sampson also notes, is the manner in which the author has turned indigenous humans—who often guided explorers—into panserbjørne. Panserbjørne are armored bears with their own kingdom on the island of Svalbard. Sampson focuses on how “the panserbjørne serve a structural purpose that is not entirely unlike that of the colonial native in Victorian Imperial texts” (60). He continues,

The panserbjørne…play out the familiar drama of the noble savage versus the colonized native who would be a Westerner. The one is permitted to excel at certain things (provided they are aligned with essential, natural forces) in order to chastise and correct certain excesses of the Western world; the other is a parody of what happens when ethnic and racial hierarchies are inverted and the subaltern grotesquely puts on the mantle of the master. Both figures appear in Victorian literature, and in both cases, they exist to secure intellectual Anglo-European ascendency over some ethnic or racial ‘other’ (60-61).

Sampson focuses on how the panserbjørne reflect general stereotypes about indigenous people, but Pullman’s bear kingdom often very specifically replicates British and American observations and interpretations of Inuit culture in the Arctic, from complaints about the “natural stink” of their habitations (Pullman 335), to lessons on how to butcher and eat a seal (Pullman 356). Artic explorers frequently documented and commented upon hunting and meat-eating amongst the Inuits, as well as the associated smells: Frobisher watched in horror while Inuits ate raw meat (Loomis 96), while a later explorer Charles Francis Hall describes being taught to eat rotting caribou brains in order to survive the winter (Loomis 177). The well-known documentary of the daily life of an Inuit, Nanook of the North (1922), includes multiple hunting and meat preparation sequences. Additionally, Arctic accounts are particularly filled with comments about the contrariness of Inuit people, similar this one from Pullman’s character Lee Scoresby: “They’re strange, en’t they, bears? You think they’re like a person, and then suddenly they do something so strange or ferocious you think you’ll never understand them” (Pullman 316). Lastly, the partial adoption of human dress and Christian practices amongst some of the bears closely aligns with descriptions of the remaking of European trade goods and artifacts (such items recovered from the Franklin Expedition) by Inuit people and the religious syncretism often noted by European observers. The heroine of the novel, Lyra, tempts a bear who wants to be more human with this offer: “when you’ve got me as your daemon, you could be baptized if you wanted to, because no one could argue then. You could demand it and they wouldn’t be able to turn you down” (342). Her words reveal a patronizing awareness that the bear does not fully understand the nuances of human culture. Though many of the instances mentioned above align with colonial descriptions of non-Inuit indigenous people, when considered together, they seem to indicate a pattern of adherence to British and American accounts of life in the Arctic. Inuit people wore (and wear) pants and other articles of clothing made from the skin of polar bears, so this shift in depiction requires only a small amount of imagination and a willingness to accept colonial narratives.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

2 The flavors of different parts of the seal are compared to common British foods to reveal how securely the heroine, Lyra, has adapted to life in the Arctic (or adjusted her perceptions of that life).

3 Scoresby appears to be named after the real-life Willam Scoresby, a British whaler who documented many useful scientific and geographic findings in the Arctic that were not fully acknowledged by the British establishment due to his social class (Tyson 35 – 38).

The flavors of different parts of the seal are compared to common British foods to reveal how securely the heroine, Lyra, has adapted to life in the Arctic (or adjusted her perceptions of that life).

What happens when indigenous characters show up in bear clothing, but are otherwise unchanged from the stereotypical ways they appear in the accounts of explorers? Panserbjørne align closely with the accounts of a specific culture, reinforcing historical colonial relationships—and possibly the “rightness” of that kind of relationship—regardless of the obfuscation of shifting species. At the end of The Golden Compass, panserbjørne guide Iorek Bynison cannot carry Lyra for the last few steps of her journey because he is too heavy to traverse a bridge over a crevasse. He explains, “The tracks go on… But I cannot” (386). Thus, in the end, the tiny blonde British child of the city is mightier than the massive armored polar bear of the Arctic. After losing control of the American colonies in the late 1700s, the British government redoubled efforts to reach the North Pole as a matter of national pride, offering thousands of dollars in reward money for the first to reach the pole (as well as for those who neared it) (Tyson 34). The pole was not reached until the 20th century, and though there is ongoing dispute about who reached it first, no one thinks it could have been an Englishman. In a sense, Lyra’s journey reclaims this victory for England and British exceptionalism.

Corey Sampson writes of The Golden Compass that “There is much to arrest our imaginations in it” (46). I might argue for a different version of “arrest” than Sampson intended—that, at least in this regard, this story might be pausing our ability to imagine rather than astonishing or enchanting us. Why are we so often unable to invent beyond history or our conceptions of history? A lack of desire, or a failure of imagination? As one sensitivity reader discovered when the release of his own novel was canceled due to insensitivity, even the most “woke” among us can be subject to the idealistic policing of young adult fiction (Waldman). Our stories tell us who we, and who we are is often not who we want to be. As Sampson writes, “Our responsibility as literary critics, however, is not to let the shadows of imperialism go unchallenged, even in acclaimed works of literature” (74). I would add that our other work, as critics and writers and humans, is to do the difficult task of imagining.

Works Cited

Alter, Alexandra. “In an Era of Online Outrage, Do Sensitivity Readers Result in Better Books, or Censorship?” The New York Times, 24 Dec. 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/24/books/in-an-era-of-online-outrage-do-sensitivity-readers-result-in-better-books-or-censorship.html. Accessed 30 Sep. 2019.

Hecker, Anna. “The Problem with Sensitivity Readers Isn’t What You Think It Is.” Writer’s Digest, 16 Jan. 2018, https://www.writersdigest.com/editor-blogs/questions-and-quandaries/problem-sensitivity-readers-isnt-think. Accessed 30 Sep. 2019.

Loomis, Chauncey. Weird and Tragic Shores: The Story of Charles Francis Hall, Explorer. New York, The Modern Library, 2000.

Pullman, Philip. The Golden Compass. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Sampson, Cory. “Pullman and Imperialism: Navigating the Geographic Imagination in The Golden Compass.” Children’s Literature and Imaginative Geography, edited by Aïda Hudson, Ontario, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018, pp. 46 – 75.

Tyson, Captain George E. Arctic Experiences: Aboard the Doomed Polaris Expedition and Six Months Adrift on an Ice-Floe. New York, Cooper Square Press, 2002.

Waldman, Katy. “In Y.A., Where is the Line Between Criticism and Cancel Culture?” The New Yorker, 21 Mar. 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/books/under-review/in-ya-where-is-the-line-between-criticism-and-cancel-culture. Accessed 30 Sep. 2019.

“Is My Novel Offensive?” Slate, 08 Feb. 2017, https://slate.com/culture/2017/02/how-sensitivity-readers-from-minority-groups-are-changing-the-book-publishing-ecosystem.html. Accessed 30 Sep. 2019.