New Uses for Orientalism

Wider Applications of a Versatile Theory

by Tom Durwood

ABSTRACT A college lit teacher makes the argument for broader applications of the late Edward Said’s literary theory of Orientalism. The author argues that Professor Said’s framework of clashing cultures has only grown in relevance since its 1978 publication, and can now lend us and our students critical insight into such diverse phenomena as modern farming, the invasion of Ukraine, beauty, our museum crisis, Shogun, the Hawaiian fires, both Dune movies, and the Immortal Bruce Lee.

INTRODUCTION

The scholar Edward Said (Si-yeed) has been gone for 22 years this November.

The ideas in his bombshell 1978 work, Orientalism, deserve a revisit. They are useful in a surprisingly wide range of current phenomena. I recommend them to you as another tool in your arsenal of understanding as you face the complex modern world.

Said began with a literary construct of how the West views the East and built a model of empire and imperial mechanics, as cultures are assimilated and narratives joust for position. Literature is but one tool in the ongoing process of empire — that is, one nation controlling another.

Now is an excellent time to lift Edward Said’s powerful ideas out of the context of libraries and classrooms and apply them to a broader range of phenomena. “Our role is to widen the field of discussion,” writes Professor Said in Orientalism.

Professor Said’s work is vast and elegant. My version of it in this brief essay will seem choppy and simplistic.

HIS IDEAS

The first law of Orientalism is that literature is a battlefield of representation and identity. She who tells the stories wins. Narratives – and this includes narratives of all kinds – are a powerful element of imperial domination.

A second tenet is that an empire is meant to devour lesser or vulnerable cultures. Narratives which ‘Otherize’ members of the rival culture help the dominant culture conquer and remain in power.

In recent centuries, we can see this mechanism in action as the two “unequal halves” of the world, East and West, Occidental and Oriental, have reached out towards one another and interact. Christendom formed a construct of superiority, capturing the “Oriental” or “Other” by defining it not in its own terms, but in Western terms. The Arabian Nights is one such work. The stories in Richard Burton’s collection of colorful tales had almost nothing to do with actual Arabians, but rather depicted corrupt, eros-drenched lands populated by bandit kings, Dragon Ladies, dagger-wielding thieves and seductive temptresses. Upright, logical, honest Westerners tended to prevail.

Orientalism as a model is about the treatment of any minority culture, not just Asian. We tend to depict the world in terms of Us and then the Other – this “other” could be Chinese, or Navajo, or black, or female. The key is that we steal or take hostage that conquered culture’s actual identity by giving it the identity that serves us … usually a cardboard cut-out. It suited pulp-fiction writers to depict all tribes of American Indians as savage Comanche warriors – even though the Zuna were peaceful cave dwellers, and other tribes had other identities. We needed Native Americans to be depicted as bloodthirsty, since our brave soldiers and settlers and cowboys were at the time pitted against them over who controls Arizona. Since the Comanche and Zuma did not write any books, they were helpless against this identity that we created for them.

Joseph Conrad conceiving of the African identity is Joseph Conrad owning African identity. On the battlefield of representation and identity, a well-told story is a powerful form of control. This process of cultural misunderstanding is not evil, more so it is a mechanism that takes place when two cultures first meet, and vie for dominance. One wins. This is what empires do.

The lesser culture becomes alien in the eyes of the ruling class – the Other.

The Other character in stories – Grendel, the Mexican soldiers who storm the Alamo, the Wicked Witch, the berserk barbarian — has no personality, no backstory, no family, no tribal traditions, no likeable traits whatsoever. He or she exists to get outwitted and defeated by the Occidental hero (Hercules, Wonder Woman, Davy Crockett, Indiana Jones, etc.).

Eventually, new stories and new writers come along to correct the false imagery. It can take centuries for the colonized to assert their own stories, and music, and language, replacing the caricatures with real heroes. Surely it is a universal sign of success when this happens … producing an integrated or mixed culture stronger than the previous mono-regime.

Implicit in Said’s work is the idea that successful empires integrate the two cultures. I will go a little further and assert that:

All empires are marked by how well they assimilate the talents and culture of its colonized.

That empire which best transforms its Others into citizens will be the most successful.

________________________________________________________________________

We are at a point in our work when we can no longer ignore empires and the imperial context in our studies. – Edward Said

________________________________________________________________________

Now let’s see if we can find wider uses for this ingenious set of ideas.

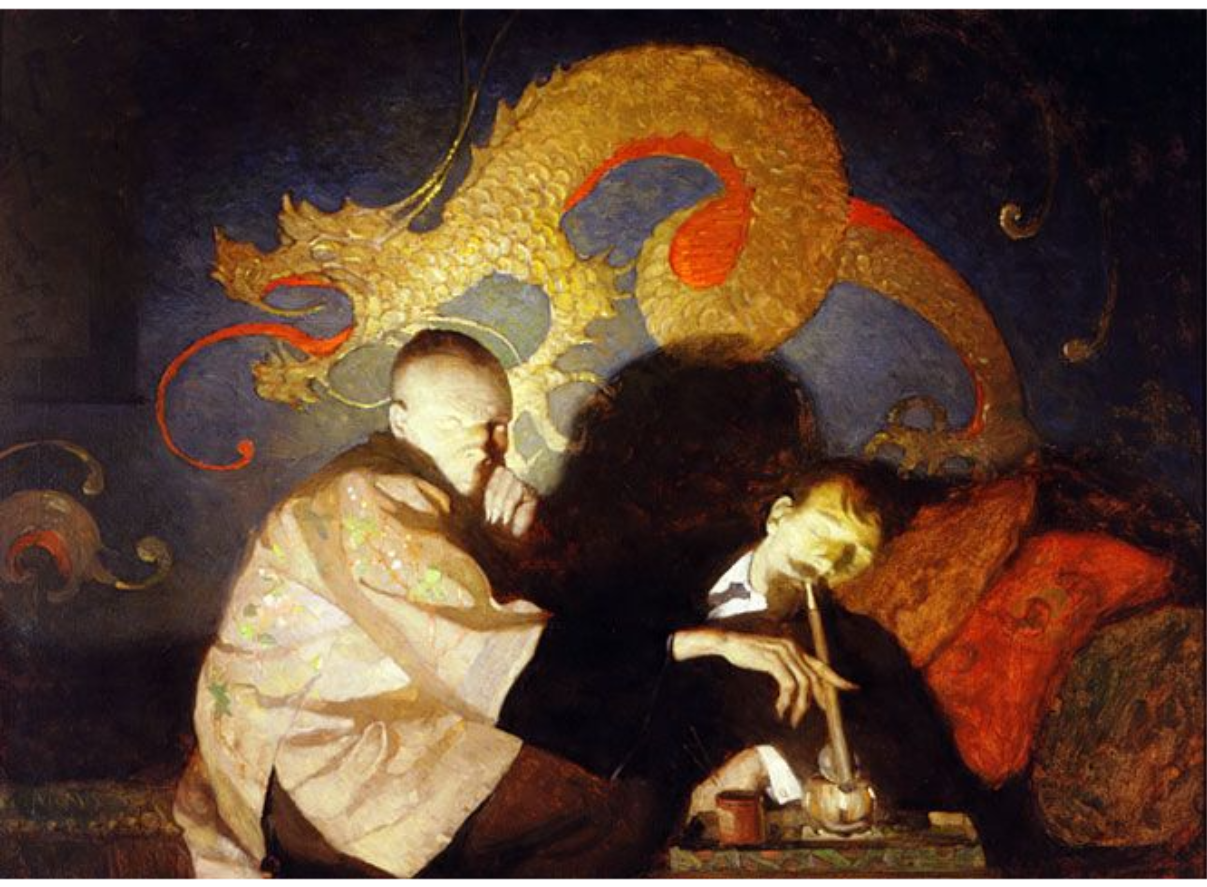

The Opium Smoker, by NC Wyeth (1913)

FARMING

If literature is a combat zone taking place in our collective imagination, then agriculture represents a real-world war being wages in crop fields of soil, seeds, fertilizer and reaper around the globe.

On one side is the modern Imperial food system, a juggernaut of high yields, genetically modified crops, copyrighted hybrid seeds, corporate fertilizer and pesticide systems, lenders and lawyers, expensive machinery. It began with the American botanist Norman Borlaug and his Green Revolution. His dwarf wheats and hybrid tomatoes produced incredible yields per acre, but there is a catch: they depend on expensive pesticides and fertilizers and laboratory-born, copyrighted seeds.

On the other side are family farmers, planting a variety of heritage plants with traditional methods and ancient seeds. Congressman Earl Blumenauer of Oregon is one of those sticking up for the minority culture of farming. “We simply pay too much to the wrong people, to grow the wrong foods the wrong way, in the wrong places,” Blumenauer said. He has a completely different vision for how 40% of the country’s land looks and works, and it involves a lot less genetically-modified monocultures.

The trade-off to acquire high-yields is steep. Activists like Vandana Shiva of India, Kenyan nutritionist Maureen Muketha, and Jyoti Fernandes of the Landworkers’ Alliance have found Noman Borlaug’s Green Revolution to be a mixed blessing. According to Shiva, “soaring seed prices in India have resulted in many farmers being mired in debt and turning to suicide.” There are fewer alternatives to mega-farms, with their monocultures. Shiva argues that the seed-chemical package promoted by green revolution agriculture has depleted fertile soil and destroyed living ecosystems. Agrarian distress is global.

This, I feel, is very much a Saidian landscape. Every empire must feed its citizens. Who owns that capacity? The imperial green-revolution giant industrial farms stomping (or failing to accommodate) the folk or family farmer. In the end, we will need those land-race seeds — the inherited strains of legacy crops — which are being shoved aside for high-yield synthetic crops. A disciple of Professor Said might point out that the imperial system of corporate agriculture tends to steamroller small folk farmers from Nebraska to Uttar Pradesh to the Pearl River Delta, stomping on centuries-old agriculture methods.

Now the drama grows more complex, as empires invade one another’s farmland. A rural community in Michigan has hailed a ‘huge victory’ after a Chinese-owned industrial firm backed out of buying local farmland.

The Orientalist model seems to have a lot to contribute to the ongoing and nearly universal wars of food sovereignty.

________________________________________________________________________

Every empire regularly tells itself and the world that it is unlike all other empires, and that it has a mission, certainly not to plunder and control, but to educate and liberate the peoples and places it rules directly or indirectly. — Edward Said

________________________________________________________________________

MUSEUMS’ EXISTENTIAL CRISIS

Right now, a reckoning is rippling through Western museums. They are being asked to reconsider centuries of collecting cultural artifacts from Eastern cultures – also known as looting.

“I am secretary of the Smithsonian. We commit to a long-overdue reckoning,” writes Lonnie G. Bunch III in a recent editorial. The Smithsonian, like so many museums, is rethinking its reason for existence.

Western museums’ collections of beautiful Oriental art and artifacts are preserved and displayed for the ruling classes to admire in spacious, air- conditioned splendor. It looks more like stealing, to the colonized.

In a world of empires, of course, the colonizer brings back the conquered tribes’ treasures to proudly display at home. That is what empires do. This long-time practice of British and French and American museums showcasing Eastern art, weapons, religious artifacts and even corpses as prizes for the home crowds to admire has brought us to a tipping point. Museums are giving them back. It is a dark heritage.

The Smithsonian recently returned 29 Benin bronzes to Nigeria. The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles returned three precious terra cotta figures to Italy. The Denver Art Museum shipped four antiquities back to Cambodia. “For Cambodians, the statues are not just works of art… they are sacred deities that hold the souls of their ancestors to whom they ask for guidance and pray,” observes Phoeurng Sackona, Cambodia’s Minister of Culture.

French museums’ preservation and display (for French audiences) of Angkor Vat jewels, statues and temple art looks like sheer plunder from the Cambodian side. This would be like their displaying George Washington’s coffin or Betsy Ross’ flag in a glassed display case in downtown Phnom Penh.

“Museum directors and curators were trained under different ethical norms and now find themselves,” Elizabeth Marlowe, director of Museum Studies program at Colgate University, “in a different landscape.”

And that landscape is Saidian; a cultural battlefield in which the winner does it their way, writing the stories and displaying the art. If both sides of the opposition are smart, they even things out. Proper assimilation tends to benefit all.

Plundering a colonized people’s treasures to display behind glass for the citizens of the Empire may no longer be a valid reason to exist.

If he were here today, Edward Said might say, “I told you so.”

THE IMMORTAL BRUCE LEE

Why did the lead actor in a collection of modest action movies become such a powerful and enduring cultural hero? The answer is hard to find in the films themselves. The offerings, such as Fists of Fury and Enter the Dragon have been described by Vincent Canby, film critic of the New York Times, as making “the worst Italian western look like the most solemn and noble achievements of the early Soviet Cinema.”

Yet fifty years after his death, Bruce Lee, remains “recognizable in any village around the world,” according to Daryl Joji Maeda, Professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder. Lee is the first authentic Asian global superstar.

Why did this happen?

We can find an answer in Edward Said’s model of clashing empires.

As the West encountered the East, European authors gravitated towards depicting Orientals in a range of demeaning stereotypes. Robinson Crusoe, The Travels of Marco Polo, Rudyard Kipling’s Gunga Din, Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, and pulp authors like Robert E Howard could sell thousands of copies of literature populated by perfumed and erotic temptresses, street urchins, opium smokers, sneaky tricksters and bloodthirsty bandit kings.

Left out: Oriental male heroes.

These Otherized casts of characters served as excellent foils for intrepid European heroes to encounter and vanquish. It did not pay as well to deliver readers a fair and balanced depiction of foreigners. An empire’s mission is to dominate the lesser or consumed cultures, and to use them and their skills to enrich the empire.

It was into this this centuries-old gaping void of heroic male role models that Bruce Lee stepped. He became such an important figure on the battlefield of representation and identity because he was a legitimate Chinese action hero. According to Joel Stein, writing in Time magazine, “in an America where the Chinese were still stereotyped as meek house servants and railroad workers, he was all steely sinew, threatening stare and cocky, pointed finger… He was the redeemer.” He battled Western crooks not with guns and swords but with dragon kicks, nunchaku, lightning-fast hands, virtue, and cat-like vocalizations.

His popularity exploded across both Eastern and Western audiences.

Bruce Lee is a symbol of Asian pride. Professor Said might say that he helped give back to the Orient its ability to tell its own stories.

________________________________________________________________________

If Said were here today, he might say, “I told you so …”

________________________________________________________________________

The global narrative culture, perhaps suspicious that there might be some other hero out there. was desperate for a legitimate masculine figure from the East. Few legitimate Oriental heroes were offered in Occidental literature, to match the Western heroes’ pantheon that included such figures as Beowulf, King Arthur, Ulysses, Daniel Boone, and Sherlock Holmes.

Now the Orient has its own.

THE HAWAII FIRES

On August 8th and 9th of last year, the deadliest wildfire in over a century devoured the historic town of Lahaina on the Hawaiian island of Maui. It caused 101 death and widespread destruction, devastating the Maui community. Damages exceeded $5 billion.

No arson was found. No lightning bolts. No downed power lines.

What a shame. An act of God. Fires happen, right?

Wrong.

You, Professor Said, and I now know to look beneath the surface

to truly understand a phenomenon like this.

There, we find Sugar.

Sugar plantations are the answer to the question, Why did Lahaina burn?

It turns out that the town of Lahaina was built on top of a wetlands, an ancient water terrace, a delicate system of springs and creeks and canals that had once fed the native farms and fields. This was done to make way for the giant sugar plantation which became such an important part of Hawaiian life in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The American empire’s hunger for sugar changed Hawaii’s very landscape.

“It takes 500 gallons of water to produce one pound of sugar, a million gallons per day to irrigate 100 acres,” writes Reis Thebault in the Washington Post. America’s growing population craved soda pop and candy bars; it needed a lot of sugar. The profits were too big to ignore. The Maui wetlands had to go. “From the mid-1800s into the 1900s,” continues Thibault, “increasingly powerful plantation corporations siphoned a prodigious amount of surface and groundwater, building a booming economic empire while the wetland ecosystem suffered.”

The American investors — the sugar and pineapple industries – resorted to deforestation to more efficiently supply cheap sugar to U.S. citizens. This radically changed the Hawaiian islands’ ecosystem. It left native Hawaiians with insufficient water for their own crops. The Maui fire was inevitable.

It was the foreseeable conclusion of a clear pattern of land-use decisions over time. It was, I think, not so much an unintended consequence but the result of a setting of priorities – Imperial production and profit imperatives over traditional folk values.

________________________________________________________________________

Our role is to widen the field of discussion.

__________________________________________________________________

THE INVASION OF UKRAINE

Whatever Western nations were thinking in the months building up to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, they got it wrong. Had they re-read their copies of Orientalism, Western leaders might have seen that what seemed irrational was in fact a national longing for the return of the Soviet empire. Nothing else mattered.

We – the West – have been ignoring Professor Said by looking at Russia and seeing a culture more or less like ours. Not so. We were imposing our ideas of ourselves onto them. Russians apparently see themselves very differently – as fragments or remainders of a broken, lost empire.

“The World forgot about Russian Imperialism,” warns Chloe Hadavas in Foreign Policy magazine. “Many Westerners fail to grapple with how Russia’s colonial legacy continues to this day,” adds Alaric Dearment in Salon. Russian dictator Vladimir Putin once called the fall of the Soviet Union “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.” Failing to understand the extent of the Russian urge to replace that phantom limb of the Empire made the West [[ surprised ]] .

“The war in Ukraine is a Colonial war,” suggests Timothy Snyder, Professor of History at Yale.” He adds, “Putin’s vision is of a broken world that must be restored through violence. Russia becomes itself only by annihilating Ukraine.” Whatever image we in the West invented of Russia, it was inaccurate.

Professor Said might remind us that when two cultures merge under an empire, it is not simply lines on a map but an across-the-board merger: deep into national identity. All components of literature, narratives, art, commerce and religion play their part. So when the empire is torn apart, the phantom limb remains. The empire is incomplete without all its children.

Without Professor Said to remind us, the world forgot about the enduring force of Russian Imperialism.

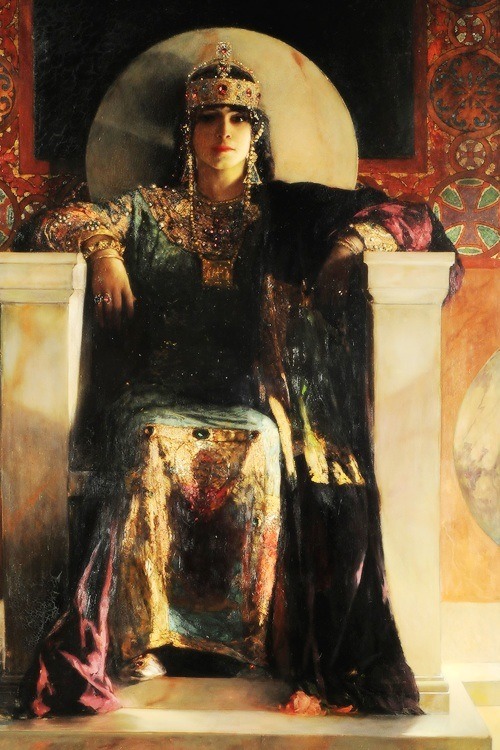

“The Empress Theodora,” by Jean Joseph Benjamin Constant (Circa 1889)

BEAUTY

One ubiquitous yet overlooked aspect of the post-colonial world is beauty. As modern Occidental and Eastern cultures have clashed and merged, Western components of female beauty – lighter skin, straighter hair, rounder eyes – have tended to win out. So fashion and beauty may constitute another battlefield in the wars of Orientalism.

Commerce has certainly taken notice. After the Korean War, Asian women created a billion-dollar market for a plastic surgery called Blepharoplasty, which rounds the eyelids for a more Caucasian shape. American news anchor Julie Chen reports that when she was a young journalist, an agent suggested that jobs would be easier to get if she had the surgery.

Global spending on skin lightening is estimated at $31.2 billion. The National Institute of Health has warned that “skin lightening for cosmetic reasons is associated with profound negative impacts on well-being and adverse effects on the skin, resulting in immense challenges for dermatologists. Despite current regulations, lightening agents continue to dominate the cosmetic industry.” The Institute regards skin lightening as a global public health issue.

As Professor Said would surely agree, Empire’s lingering impact on cultural identity is more complex than mere cosmetic. In her recent book, Decolonising My Body, Afua Hirsch confronts some of the confusing reality of existing between cultures, and how it warped her understanding of her own identity, her own body. The physical and emotional impact has run deep.

Currently, separate aesthetics for Occidental and Oriental are being re-established. Societies from Brazil to India to the Philippines recalculate desirable traits and body images. The worldwide rush towards whiteness — from hair straighteners to skin lighteners to racial surgery – is abating, in favor of multiplicities of beauty.

Current trends move away from Eurocentrism. According to Esmerelda Esquivel- Martinez of the University of California Riverside, “billion-dollar brand Fenty Beauty, owned by singer Rihanna, and Vive Cosmetics, are two examples which have been slowly decolonizing beauty …”

BOTH DUNE MOVIES AND SHOGUN

A critical moment in Dennis Villeneuve’s excellent retelling of Frank Herbert’s Dune saga comes when Dr. Liet-Kynes is checking the Fremen-devised desert survival equipment of the Atreides expedition.

She finds that the Atreides prince, Paul, already knows how to rig his sand suit. The Occidental hero knows the ways of the natives. This suggests that the boy is that rare pivotal figure who can unite the Western invaders with the Oriental natives. The idea is that Paul understands the Fremen, therefore he can co-exist with them … and presumably the combined empire can move forward. His father, the inflexible Duke Leto, is doomed by his Orientalist dogma.

It is a most Saidian moment. This is Phase 1 of the empire cycle – roots of empire – a first encounter, when the two cultures first encounter each another. A moment of understanding between West and East is the Saidian ideal. Who will win the conflict is yet to be decided.

Dune has been called techno-Orientalism, and it takes place at a point in the empire cycle before an Avatar-like colonial war over spice (gold, diamonds, drugs, crops) breaks out. Paul goes on to learn the Fremen traditions, take on a Fremen name, ride the sand-worms and fall in love with a Fremen princess. The future looks bright …. unless of course the Atreides’ Occidental rivals, the Harkonnen (Portugal? Denmark?) do the invading, all the while not counting out the Bene Gesserit (Illuminati?), who may actually be pulling the puppet strings.

Muad’ Dib’s situation as an Orientalist hero is not unlike that of Khaleesi in Game of Thrones. She is alone and army-less when we first meet her. Her eventual success comes from her ability to integrate into the Dothraki and Unsullied cultures (also, the dragons). She rises because she never considers anyone to be an Other. It makes a strong story line within the Game of Thrones saga.

So much of our pleasure in the epic clash-of-empires, James Clavell’s Shogun, arises from the closely-observed, gradual understanding between Blackthorne and Mariko, as well as the tragic consequences of cultural miscues. Both characters try to understand the other in a fairer way, brushing past the stereotypes. Professor Said would approve, I think.

CONCLUSION

Edward Said’s rich writings are the beginning of a discourse on a wide field of subjects. They can add depth and perspective to our considerations.

While some theories, born out of specific circumstances, can lose their power to explain, Edward Said’s have only gained.

John Singer Sargent, Smoke of the Ambergris (1888)