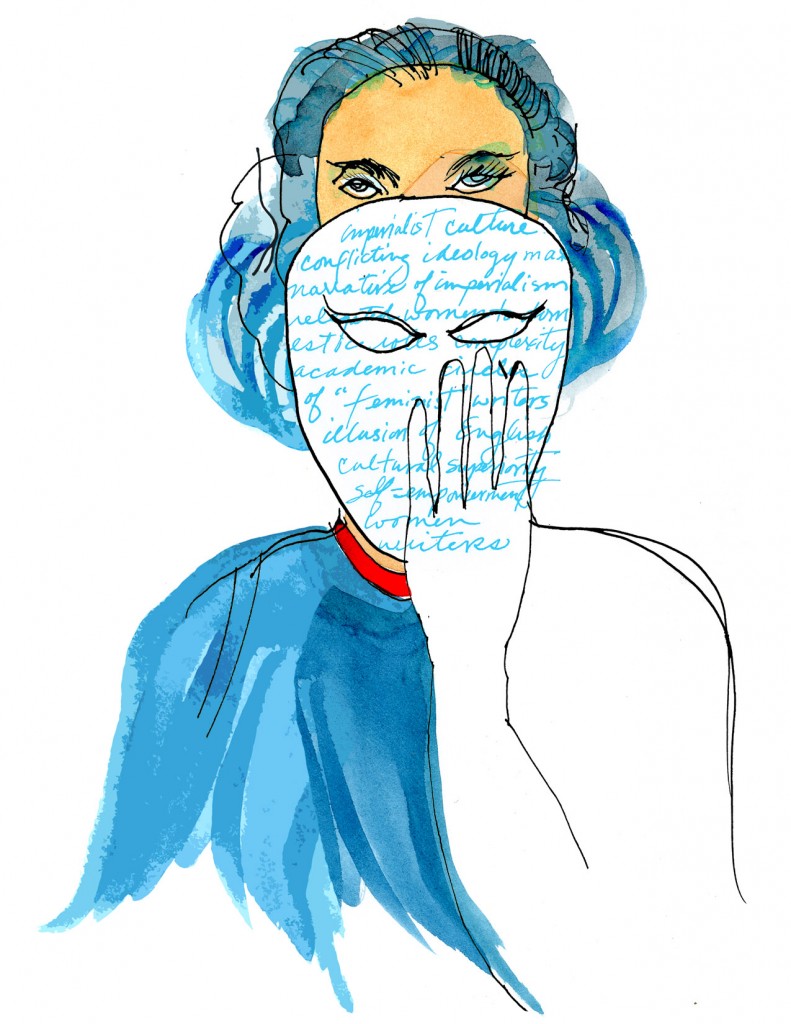

Masked Fictions

NARRATIVES OF EMPIRE

Masked Fictions: English Women Writers and the Narrative of Empire

by Nalini Iyer, Ph.D.

— Literature

— Introduction, interview, dissertation excerpt, lesson plan

Introduction

Smart people like Edward Said, Harold Bloom and, here, Nalini Iyer, see elements of imperial narratives in novels like Robinson Crusoe and Lord of the Flies. The same elements can be identified in contemporary stories movies like Avatar. As empires change, so do the stories we tell to make sense of the machineries and processes that support them.

What is an “imperial narrative”? Who cares? While her concern in this dissertation is women and their masked or coded narratives, Prof. Iyer gives us some clear answers to these basic questions in her interview and in the excerpt here. If you read her entire dissertation, you will see the in-depth scholarship which supports her arguments with specific and detailed examples of masked literature.

When she discusses historiography in the second paragraph of the excerpt, she means the process of writing history.

My students always enjoy writing like this. It seems at first to be hopelessly obscure – but we quickly see that their favorite books, movies and television shows carry many of these same elements (particularly encounters with the Other, whether ET: The Extraterrestrial or Harry Potter, a vampire in Twilight or a warrior in Last of the Mohicans). A topic like this one can propel a study unit on the Other that lasts for weeks, and one that dovetails as easily with sociology as it does with literature.

Interview with Nalini Iyer 07/2011

I should preface the responses to the questions below by noting that this dissertation was begun in 1991 and defended in 1993. As with any dissertation, it was an apprentice work of a novice scholar. After more scholarly experience and, hopefully, a more nuanced understanding of the field, I think that some of my thinking is likely to be more complex than it was 20 years ago. Also, when this dissertation was written, the field of colonial discourse studies/postcolonial studies was still new. Graduate and undergraduate courses in postcolonial theories and literatures, journals and conferences dedicated to the field, and the numbers of scholarly works were relatively fewer than they are today. So this dissertation needs to be read and discussed within these parameters.

–Nalini Iyer

You mention works such as Robinson Crusoe and Lord of the Flies as examples of classic “empire narratives.” What does that mean? What are the elements of an empire narrative?

Narratives of empire such as Robinson Crusoe, Lord of the Flies, Heart of Darkness have some of the following elements: the arrival of a European male in a new land populated by “savage” others or unpopulated, the ingenuity of the European male in surviving in a hostile environment, the taming of the landscape, encounters with the other and occasional glimpses into his humanity, and the establishment of European civilization as normative. Of course, narratives of Empire also betray European anxiety about the imperial process occasionally and then stage that with concerns about “going native” and the corruption of the European’s soul. I think Achebe’s essay “ An Image of Africa”, Jenny Sharpe’s Allegories of Empire, and Anne McClintock’s Imperial Leather colonial discourse in English literature and culture quite well.

How can a domestic story like Jane Eyre be a narrative about empire?

The argument in my dissertation was that imperial adventures, administration of the colonies, and exploration were usually the prerogative of men. While there were some women who did travel and explore, the majority of women who did go to the colonies were wives of soldiers and administrators or missionaries. For women writers who were struggling against patriarchy at home, the colonial experience had to be domesticated in terms that were familiar to them and to stage their own narrative of empowerment. Again Gayatri Spivak, Jenny Sharpe have made strong cases for Jane Eyre and colonial discourse embedded in that narrative.

Why did women need to mask their narratives, or write in code? Do they still do this today?

The prevailing attitude was that the colonies were no place for women. Marlowe in “Heart of Darkness” remarks that women had no understanding of that world, Virginia Woolf notes in Mrs Dalloway about Lady Bruton that she could have commanded armies and empires and yet her character was unable to write a letter without Richard Dalloway’s help. In narratives about the colonial enterprise in India, the memsahib was a reviled figure and we see this in E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India and in George Orwell’s Burmese Days. Of the three writers, Charlotte Bronte, Virginia Woolf, and Doris Lessing, that I focus on in the dissertation only Doris Lessing had actual experience in a colony as the child of emigrant farmers. These women writers’ primary focus was the struggles of women with domesticity and patriarchy and they felt an empathy with the colonized other and also struggled with their complicity as English women in the colonial enterprise. The colonial experience is cast in terms that the women knew in a domestic narrative and is coded as a feminist narrative. The struggle between complicity and resistance raises complex questions about celebrated feminist narratives and their problematic politics.

Has the narrative of empire changed over time? Is it different in different nationalities?

Since empires evolved with time and each imperial nation had its specific history, narratives of empire are historically and culturally contingent. My study focused on British narratives.

Harold Bloom wrote that Iago did to Othello what Europe did to Africa: that the characters captured the same dynamics as that between the empires. Are there narratives of empire in Shakespeare’s works?

I think that Shakespeare’s plays reflect England’s thinking about the other at that time. For me, the narrative of empire emerges in British literature in the 18th century.

Are there classic and masked narratives of empire today? Would Avatar or The Color Purple or Bend It Like Beckham or Harry Potter be narratives of empire? Why or why not?

Avatar definitely can be read in the same way that Achebe reads “Heart of Darkness”. It is a narrative that tells us more about American anxieties about its imperial ambitions and also, I think, demonstrates fear about declining economic and military power of the United States. For me The Color Purple is a classic womanist narrative and not a narrative of Empire. Bend it Like Beckham is a film that I read in the context of Asian experience with immigration to Britain. While that immigration is a product of the British empire in India and Indians in the UK still struggle with racist attitudes that evolved during the Raj, that film is much more a feminist text about a young immigrant girl coming of age and negotiating the challenges of two cultures. My problem with that film is that everything Indian is represented as oppressive and everything English as liberating. Once again, a feminist narrative whose politics are complex.

You analyze Doris Lessing’s science fiction as rich in imperial parallels. What are the best examples?

Shikasta perhaps is the best analysis of imperialism in that genre by Lessing.

Excerpt from “Masked Fictions: English Women Writers and the Narrative of Empire”

GENDERING COLONIALISM:

LOCATING THE WOMAN IN THE NARRATIVES OF EMPIRE

The growth, establishment and maintenance of the British Empire as an economic and political institution relied mostly on British man power. Over time, the role of British women in Empire building increased, but they were involved indirectly because they did not control the politics and economics of the colonies. Despite the increasing numbers of English women entering British colonial possessions, their role was limited. Often their relationships to men as wives, sisters, and daughters took them to the colonies, and they became a part of the Empire. In other words, the men in their lives negotiated their presence in and relationship to Empire. It was only in the late nineteenth century that English women began participating more directly in Empire building as missionaries and nurses, but their numbers were small. The indirect relationship of English women to the Empire by no means reduced their impact on it, but it made a difference in the nature of their contribution to it.

The relationship of English women to imperialism and its ideology is a complex one. They were marginalized within their own societies because of their gender, and as a consequence they were denied such imperial opportunities available to men as exploration, administration, militarism, and so on. Susan Bailey, Nupur Chaudhuri and Margaret Strobel, scholars who have explored women’s roles in the British Empire, suggest that the view of English women as marginalized by imperialism is in part a problem of historiography. Bailey argues that colonial historiography has privileged male realms of experience and that the general silence regarding women’s roles is indicative of the patriarchal bias in our own times as well as in the British imperial days. Silence about women’s roles does not indicate their passivity, and that “while women did not generally rule, they did play important roles in shaping the atmosphere in which control was exerted.”

________________________________________________________________________

Over time, the role of British women in Empire building increased … their sphere of influence was the household.

________________________________________________________________________

Bailey’s assessment of imperial historiography as masculinist is accurate. However, in her zeal to accord English women a place in imperial history, Bailey overlooks the complexity of their roles. Historically, although English women went to the colonies in increasing numbers, there were still fewer women than there were men. Furthermore, they went to the colonies primarily as wives, sisters, and daughters of male soldiers, administrators, and settlers. Their sphere of influence was the household. P.J. Marshall notes that in India, for instance, the British soldier was discouraged from taking a wife with him on his first appointment. The civil servants too were often young men who had recently completed their education. Their salaries often were not adequate to maintain a wife and family. When they were reasonably established in their careers, these young men returned to England in search of a wife or they married female relatives of fellow colonials who were present in India. Throughout the nineteenth century, single women visiting India were targets of cruel jokes as they were thought to be husband hunting. Marshall points out that they were subject to humiliating experiences such as inspections by single men when they arrived in India. Although English women were arriving in large numbers in India, in 1902, the male-female ratio amongst the British population was 384 women for every 1000 men, and most of the women were part of the man’s household. These figures suggest that silence regarding English women’s roles in the British Empire is not simply a problem of colonial historiography, but also a reflection of the social emphasis on men as builders of Empire.

The British imperial experience, both male and female, has spawned a large number of narratives that record different aspects of the imperial experience, both real and imagined. However, the narratives produced by men and women differ because of the qualitative difference in their experiences. The narratives of Empire created an image of the subject peoples and functioned as a means of exerting cultural control. Edward Said suggests that narratives are crucial to imperialism. Because the main battle in imperialism is over the control of land, Said contends that “when it came to who owned the land, who had the right to settle and work on it, who won it back, and who now plans its future—these issues are reflected, contested, and even for a time decided in narrative.” Narratives, therefore, functioned as tools of imperial control as well as tools of resistance. Said argues that the power to create narratives or to suppress them establishes an important connection between culture and imperialism (xiii).

But, critics like Said who have examined the relationship between narratives and imperialism have not studied in detail the relationship between gender and the production of these imperial narratives. For instance, when narratives of control were produced by Britain regarding its colonial subjects, it was also generating narratives that relegated women to a secondary role. Cultural narratives regarding women’s physical and intellectual frailty successfully kept them out of the positions in which they could exert social and political control. Consequently, British women’s narratives of Empire were subversive because they claimed control over territory through narrative. In enacting their resistance and empowerment through their narratives of Empire, British women writers found themselves in a contradictory situation. On the one hand, they were resisting patriarchal ideology by constructing narratives of empowerment. On the other, because they used narratives of Empire that exerted control over subject peoples to enact their empowerment, British women writers also propagated an imperialist and patriarchal ideology. The dynamics of resistance to patriarchy and complicity with imperialism in the narratives of some British women writers is the subject of this dissertation.

________________________________________________________________________

Edward Said suggests that narratives are crucial to imperialism … the power to create narratives or to suppress them establishes an important connection between culture and imperialism.

_______________________________________________________________________

In the last fifteen years, many scholars have studied the relationship between narratives and colonial ideology. (Some of these studies are discussed in the net section of this chapter.) Because colonial discourse has been delineated as a construction of knowledge that is non-differentiated by gender, many of these studies have underemphasized both the representation of English women in male narratives of empire and also the dynamics of resistance and subjugation in female narratives of Empire. Furthermore, because imperial narratives have been identified as those that directly explore the imperial experience, either real or imagined, most of the narratives discussed in studies of colonial discourse are those produced by men. Consequently, such novels as Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, Joyce Cary’s Mr. Johnson, or accounts of exploration such as Alexander von Humboldt’s Personal Narrative, or Henry Stanley’s account of meeting David Livingstone have become paradigms of the narrative of empire. Occasionally, a novel like Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte or Mary Kingsley’s account of her exploration is discussed. Because the narrative of empire is connected to the possibility or actuality of direct contact with the colonial other, many imperial narratives by women writers have been overlooked. Furthermore, narratives by women often fall under the rubric of “feminist” narratives. As a consequence, narratives by women that address imperial questions have been studied from the feminist point of view and any problems with these women writers’ politics regarding the colonial other have been overlooked. This dissertation argues that because women were culturally marginalized or excluded from the imperial experience, they had to address imperial issues indirectly and many ostensibly domestic narratives are masked fictions of empire. This chapter engages in a discussion of the following: the masculinist nature of academic theorizations of colonial discourse; the exclusion or victimization of women in male narratives of empire; and masked fictions of empire.

Male-Centered Academic Discussions of Colonial Discourse

In recent years postcolonial cultural historians and scholars have rewritten Western history with a view to unearth “the disturbing memory of its colonial texts that bear witness to the trauma that accompanies the triumphal art of Empire.” Edward Said’s Orientalism (1979) was a pioneering work in this area. Orientalism demonstrates that the production of knowledge regarding the “Oriental” world was a means of creating and maintaining control over a different world.” Said argues that “Orientalism is more particularly valuable as a sign of European-Atlantic power over the Orient that it is a veridic discourse about the Orient.” Orientalism is significant because it suggested that studies of colonial narratives should go beyond merely describing the images of empire in imperial texts because colonial discourse embodies an hegemonic relationship between the colonial power and its colonized subject. The dynamics of empowerment and subjugation which are played out in the narratives of empire should be the focus of the studies of colonial discourse. Said’s Orientalism provided subsequent works with a methodology for the study of Western cultural productions and imperialism.

Orientalism is remarkable for the impact it made on a generation of scholars and critics who Said has aptly named “the children of decolonization.” However, one of the problems with Said’s interpretation of Western history and narrative is that he does not distinguish between the narratives produced by men and those written by women. Said, Bhabha, Brantlinger, and others who have studied colonial discourse have constructed it as a non-gendered body of texts. Brantlinger’s Rule of Darkness catalogs the images of empire in Victorian literature and analyzes the writing of both male and female authors. He argues that imperialism was an intrinsic part of Victorian thinking, but he does not question the ideology of gender that also shaped much of Victorian thought including the imperialist mindset. Bhabha in characterizing colonial discourse presents gender and class as subordinate issues. He argues that

The objective of colonial discourse is to construe the colonized as a population of degenerate types on the basis of racial origin, in order to justify conquest and to establish systems of administration and instruction. Despite the play of power within colonial discourse and shifting positionalities of its subjects (e.g., effects of class, gender, ideology, different social formations, varied systems of colonization etc.), I am referring to a form of governmentality, that in marking out “subject nation,” appropriates, directs and dominates various spheres of activity.

The factors that Bhabha relegates to parentheses splinter his notion of colonial discourse as a homogenous body of knowledge. Colonial discourse is not simply predicated on an ideology of race. Issues of class, gender, and varied systems of colonization also shape colonial discourse.

Addressing the question of gender and colonial discourse, Nupur Chaudhuri and Margaret Strobel suggest that historians of empire and scholars of women’s history have functioned in intellectual isolation until recently. They suggest that women’s history and imperial history share common territory. Gayatri Spivak had argued earlier in her famous essay “Three Women’s texts” that some western feminism is problematic because even as it celebrates female individuality it engages in a process of othering the third world and establishing the cultural hegemony of the West. Spivak’s essay emphasizes the racial exclusivity of some western feminism. Neither feminist discourse nor colonial discourse should be constructed as monolithic entities. In recent years, many works have emerged that explore the connections between colonial discourse and feminism. Notable among them are the following: Suvendrini Perera’s Reaches of Empire (1991); Sara Mills’ Discourses of Difference: An Analysis of Women’s Travel Writing and Colonialism (1991); Moira Ferguson’s Subject to Others (1992); Nupur Chaudhuri and Margaret Stroebel’s Western Women and Imperialism (1992).

Despite the scholarship on British women’s writing and its relationship to the ideology of Empire, academic theorizations of colonial discourse retain the illusion of colonial discourse as non-gendered. Edward Said’s most recent work Culture and Imperialism (1993) is a case in point. Said claims that this new work builds on Orientalism and tries to remedy some of the omissions and problems with that earlier work. He acknowledges that Orientalism like other studies of the Middle East at that time was “aggressively masculine.” However, despite this recognition Culture and Imperialism does not engage in a substantive discussion of gender. For instance, when Said reads Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park as propagating imperialist ideology, he comments that “Austen sees what Fanny does as a domestic or small-scale movement in space that corresponds to the larger, more openly colonial movements of Sir Thomas, her mentor, the man whose estate she inherits. The two movements depend on each other.” Why does Austen place Fanny’s actions within a smaller domestic space? Why does Fanny’s access to the larger “more openly colonial movements” of Sir Thomas have to depend on her inheritance of his estates? Said’s analysis of Austen provokes these questions, but they are not answered in this book. Said equates the actions of Sir Thomas and Fanny, but he erases the gender difference implied in Austen’s text. Fanny has to operate on a small scale because culturally she cannot access Sir Thomas’ world except by inheriting his ill-gotten gains. Fanny’s inheritance economically empowers her, but it also places her in the role of the exploiter of slave labor in the West Indian plantations that she inherits. In erasing the gender difference between Fanny and Sir Thomas, Said’s analysis of Mansfield Park overlooks the dynamics of Fanny’s empowerment that changes her relationship to her culture and to its imperialist ideology.

________________________________________________________________________

Fanny has to operate on a small scale because culturally she cannot access Sir Thomas’ world …

________________________________________________________________________

Culture and Imperialism continues the masculinist emphasis in academic theorizations of colonial discourse. This masculinist emphasis can be attributed to the patriarchal nature of British imperialism itself. Narratives of British imperialism have reflected the patriarchal nature of imperialism and studies of these narratives have continued their male-centeredness. The next section of this chapter will examine the depiction of women in two male narratives of empire, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India. Both these novels have been key texts in discussions of British imperialism.

Male Narratives of Empire

The novel that Ian Watt referred to as the preeminent novel of the “individualism” that characterized modern realistic fiction was also a significant narrative of Empire—Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. The narrative of Crusoe’s shipwreck, his survival skills, and his meeting with Friday has become so popular that Martin Green suggests that it is easily recognized in the West whether an individual has actually read Defoe or not. Green also remarks that it is the most retold story in British literary history, spawning such novels as The Swiss Family Robinson, Coral Island, Lord of the Flies, and so on. Because the Crusoe story has been significant in British cultural history, postcolonial narratives of resistance have also appropriated it and retold it from the perspective of colonized people. Derek Walcott’s Castaway poems, his Pantomime, J.M. Coetzee’s Foe are among those subversive rewritings of Robinson Crusoe.

Robinson Crusoe has become central to debates on colonialism because of its celebration of British culture and its Christian moral justification of the enslavement of Friday. Crusoe, who had himself been enslaved by Moors and subsequently escaped from them, exhibits ambiguity on the issue of slavery. He recognizes the loss of personal freedom and its accompanying humiliation when he is a slave himself. He celebrates his skill and ingenuity at having escaped his enslavement. But he has no qualms in selling Xury into bondage when it results in pecuniary advantage for himself. As a planter in Brazil, he offers his seafaring skills to his neighboring planters in order to procure cheap slave labor from Africa for their plantations. For Crusoe, enslavement of British subjects is deplorable, but enslavement of people of other cultures is justifiable especially if it is in the interests of Christian values. Therefore, the narrative pardons the enslavement of Xury and Friday because Xury is promised his freedom once he becomes a Christian and Friday on becoming Crusoe’s slave is also gradually converted to Christianity.

________________________________________________________________________

In making a new life for himself, Crusoe imitates English life and engages in converting the “savage” he encounters to both English and Christian ways of life. ________________________________________________________________________

Robinson Crusoe is also a colonial allegory because Crusoe’s “civilizing” mission on the island borrows from contemporary British ideology of colonial expansion and also projects an ideal colonial situation. During his years of solitude on the island, Robinson Crusoe cultivates it and makes it habitable. With a few remnants of British life saved from the ship, he forges a new way of existence adapting himself to his new environment. Crusoe’s “new world” is both Christian and English. In making a new life for himself, Crusoe imitates English life and engages in converting the “savage” he encounters to both English and Christian ways of life. Martin Green argues that Robinson Crusoe is both an imperial narrative and an anti-imperial narrative because Crusoe’s new world is based on “self-help, not hierarchy, of the adventures of the individual, not official authority. The idea of empire is attached to the Spaniards with their silver mines, their cruelty to the Indians, and their Inquisitions. Crusoe represents the opposite of all that.” However, Green’s defence of Defoe is Anglocentric because it subscribes to Crusoe’s justification of his “civilizing” mission.

Crusoe tries to create a new culture in the image of the one he has left behind. His new world has its own identity too because it has only retained a part of English life and not all of it. Crusoe’s trips to his rescued ship and the material he salvages from it that he uses to build his new community symbolize the blending of the new with the old. However, this new culture is exclusively male. At first, because of his circumstances, he is the sole inhabitant of the island. He soon acquires Friday and later increases the population of the island with mutineers and prisoners. In Crusoe’s new world there is no room for women.

The entire novel has very few female characters. The first woman in the narrative is Crusoe’s mother who both thwarts and abets his seafaring ambitions. After his rescue from the island, Crusoe meets the widow of his partner who has managed his finances for him during his time on the island. At the end of his tale, Crusoe mentions how five women prisoners were brought from the mainland to his island which was subsequently populated by some children. In this tale, there are only two functions for the woman. Some women, like the widow, maintain at home the order created by men. Others, like the native women prisoners, help augment the population of the new world and ensure its continuation. Crusoe’s colonial allegory establishes the colonial venture as exclusively male. Unlike later male narratives of imperialism (Heart of Darkness and A Passage to India, for instance), Defoe’s narrative does not subscribe to the notion of miscegenation because the new population on the island was of mixed racial descent. Notions of racial purity and fear of interracial relationships entered British thinking only in the mid-nineteenth century. The erasure of the white woman in Robinson Crusoe is a reflection of the diminished role of the women in Empire building at the time. Robinson Crusoe, therefore, constructs not only a narrative of enslavement and colonization of the Caribbean, but also a narrative that negates the white woman.

Nalini Iyer is currently Director of the Office of Research Services and Sponsored Projects at Seattle University, where she has also taught extensively. She earned her undergraduate degree from the University of Madras and her Ph.D. from Purdue University. Among her publications are Other Tongues: Rethinking the Language Debates in Indian Literature (edited with Bonnie Zare) and Roots and Reflections: South Asians in the Pacific Northwest (edited with Amy Bhatt).

POSTSECONDARY LEVEL

L E S S O N P L A N T O A C C O M P A N Y

Masked Fictions: English Women Writers and the Narratives of Empire

JOURNAL OF EMPIRE STUDIES SUMMER 2011

1. Does your family have a “master narrative” the way a nation or empire might have one? What is it?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

2. Are there incidents or episodes which do not fit into your family’s narrative?

What are they? Why do they not fit?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

3. How does the author say these two authors are similar? What do they share that T.S. Eliot does not share?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

4. What is the author’s thesis?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

5. Which books and authors does the author use as proof or support for her argument?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

6. In what ways is Robinson Crusoe a narrative of empire?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

7. Do women “mask” their fiction today? Can you provide three examples of such stories?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

8. Does a movie like “The Dark Knight” carry elements of empire? “The Matrix”? “The Color Purple”? “Tombstone”? “The Maids”? Can you name others?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

9. BONUS QUESTION

What is the “empire theory of literature” outlined in the article “Melville and Orwell: Two Sides of Empire”? Do you agree with it?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

10. In which quadrant of the author’s color wheel of empire does “The Great Gatsby” fit? Why? Where does “Of Mice and Men” fit? Where does “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” fit? Why?

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

This article talks aabout the issues on female writers and the narrative of empires. The article states alot of good points that show the relation of women writers masking their identity and the empire narrative.

The empire narrative has a lot to do with imperialism; the idea of superior cultures imposing their ideas upon weaker subordinates. Basically the idea of imperialism establishes who’s in charge, who has the power, and who doesn’t.

So Before English women writers had to mask their idenity in order for their literary works to be taken seriously. An example is the movie casenova, in the movie a female philosopher has to hide her identity and use an old man to pose as a philosopher and submit her work to the local paper. Due to the empire narrative, women were established as powerless and more as objects to boosts a man’s image, rather than being seen as an equal human being capable of intelligence.

This article touches the issues of the differences of how females and males write history and books. It explains how women usually are given small parts in the general story, even when their part is a bigger part than what they make it seem. The male view shows that females are almost invisible in history, whereas when women write they highlight what they have done. This article also emphasis that when women who write they are written off as strong Feminist and are almost dismissed. This is why Feminist are plenty today. This article is very informative and makes the reader think, comparing narravitves written by males to female. The examples used are very true and hit right on point. The questions also make the reader think about the article and apply it to present day as well as in the past. Overall this is a very interesting article.

This discusses the sensitive topic of the “woman vs. man” aspect of history. In many historic readings women almost seem obsolete as told by the male perspective. When women write stories of their actions they expand and broaden the story. Any woman who stands out and has a strong feminist voice are usually ignored. This article brings up many of the questions that a lot of people tend to think; women are just as important and valued as men are now we have a strong voice.