Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife

Rules of a different type of war

Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam

John A. Nagl

Mr F B K Drake (right), Civilian Liaison Officer-in-Charge of Dyak trackers

in Malaya, talks with some of his

selected jungle fighters. Photo: Central Office of Information

INTRODUCTION

There are two powerful ideas which I am constantly trying to place before my students. The first is “adapt.” In class, you are constantly receiving signals about an assignment and how you can more fully understand it. In life, there is a premium on perpetual learning, on noticing and incorporating important changes in the environment; those students at my school who succeed are those who can adapt. The second idea is this: “Look beneath the surface.” Whether it is a person, a battle, or a poem, the dynamics we discover beneath the appearance are often much more telling than what you first see on the surface.

These same two ideas are present and compelling in John Nagl’s excellent book, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam. In his close analysis of one obscure modern military campaign and one famous modern campaign, he shows us that an army is an organization which must always be prepared to learn with honesty. War, the reader quickly finds out, is not what you think it is.

Lieutenant Colonel Nagl is a warrior-scholar, having led a tank platoon in the First Cavalry Division in Operation Desert Storm, and again in Khalidiyah, Iraq. A great value he brings to the subject is his own experience with counterinsurgency.

In the following interview (which our Associate Editor Jason Ridler conducted), you can see the wide range of influences the author drew upon, as well as his reflections on America’s current counterinsurgency efforts .In the accompanying book review, I have tried to block out the main ideas for lay readers who, like me, want to understand asymmetrical warfare.

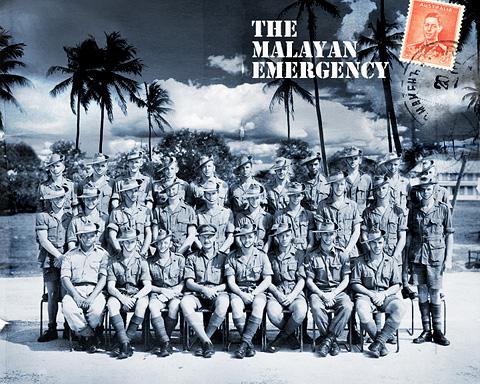

Commonwealth troops serving in the Malayan Emergency of 1948-51 were able to adapt to warfare wholly unlike that of WWII.

Interview with John Nagl, D.Phil

By Jason S. Ridler, Ph.D. 18 March 2013

Your doctoral thesis was a comparative look at the British army’s experience during the Malayan Emergency and the US army’s experience in Vietnam. Each conflict had very distinct differences in terms of geography, culture, and national tradition toward war and insurgency. What value was there in taking a comparative approach?

I was heavily influenced by the work of Dr. Alexander George [a behavioral scientist, author of Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences]. George emphasized focused and structured comparisons in case studies. Despite legions of differences between the Malayan Emergency and the Vietnam War, there were still lots of common variables under the umbrella of conventional armies learning to conduct unconventional warfare. I considered a number of other conflicts of the last century, including the Philippine/American War, perhaps the best example of American success at counterinsurgency. But I found in both Malaya and Vietnam more compelling data in comparing armies being asked to “change their spots” to fight the war they faced, instead of the war they’d prepared for. The learning bar for each was very high.

What assumptions about that war did you have before you began your research, and where they challenged, or confirmed when you finished your thesis?

I tried not to have too many assumptions at the start, and instead just wanted to investigate the questions I raise in the book about why Britain succeeded in defeating the Malayan insurgents and the US failed in Vietnam. In my analysis, the British are able to learn better, quicker, before the people at home tired of the war. To understand why the British excelled and the US faltered, I came to the core argument that organizational culture explained the different outcomes more than anything.

Gentleman, we are out of money. It’s time to start thinking.

The deep sinews of any successful organization are its capacity to learn. It took a lot of research and consideration to come to this conclusion, but the more I analyzed the two case studies, the more I began to appreciate organizational learning culture as the key to appreciating both outcomes.

While the study of organizational culture is complex, can you provide a critical insight into the difference between these two cultures to illustrate your point?

The core difference between the two, again, relates to their organizational culture. The British Army was more flexible, less hierarchical, and more open to good and different ideas. The US army at the time was less so. I should note that it’s also difficult to separate people from their cultures. The British Army had a tradition of being resources strapped, constrained financially as well as in firepower. I believe this generated a need for innovation and creativity. There’s an apocryphal quip attributed to Churchill during the dark days of the Second World War. “Gentleman, we are out of money. It’s time to start thinking.” The British never had the firepower resources that dominated American operational and tactical thinking in Vietnam. The US relied on its resources perhaps more than innovation. This complicated its ability to learn from mistakes.

Do you think the British Army’s tradition in fighting on the fringe of empires, and conducting imperial policing, contributed to this flexibility of thought?

Yes. The British Army view “small wars” as part of their core responsibility. Fighting in foreign parts of the Empire, with different cultures and geography, would require appreciating the unique differences in fighting an insurgency as opposed to conventional warfare. The US Army, despite experiences in “small wars” and insurgencies in North America and elsewhere, did not appreciate them the same way. The army was designed to fight the “big war.” Tom Ricks had a good line about this issue: for the US Army, the Civil War was the Old Testament, the Second World War, the New Testament. Unconventional warfare has never been a top priority for the US Army despite long experience with it, and that is extremely unfortunate.

Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife has a definite “lessons learned” approach to both the Malayan Emergency and the Vietnam War. Considering your own experiences and views on counter insurgency and warfare, what are the greatest lessons to be learned from each conflict for today’s thinkers on war and insurgency?

The best lessons were actually synthesized in FM 3-24 [the US Army Field Manual on Counterinsurgency, the document that provided the doctrinal framework for the “surge” in Iraq]. In my own view, some elements remain perennial. The people are always the goal, you have to win their support against the insurgent, and you have to be able to learn and adapt to local circumstances.

Revolutionary wars are fought with ideas as much as they are contested with weapons.

In learning the lessons of Malaya, I joke that if you have to fight an insurgency, do it in a peninsula where you have logistical superiority and the insurgents don’t border a friendly supporter nation, and do it before CNN is invented. All kidding aside, the British had a series of advantages but the principles I outlined, of winning the support of the people and separating them from the insurgent, were followed. Vietnam, as a tragedy and failure, is rife with lessons. One would be the importance of selecting the right commander for the job. Perhaps the biggest lesson is that Great Powers inevitably lose small wars when they lose the national will at home to support them.

You served in Iraq in 2003 as the Operations Officer of the First Battalion of the 34th Armored Regiment (the “Centurions”) after you’d finished your dissertation. So your experience in Iraq began when the US army found they were no longer fighting a strictly conventional. One of your core themes in LEARNING TO EAT SOUP WITH A KNIFE is the difficulty of changing an institution’s mode of operation. Can you discuss how, if at all, your study of Malaya and Vietnam helped you and your unit adapt to the challenges in Iraq?

(Laughs). I have a few thousand stories, but I’ll limit it to one. One critical element was the necessity of working with local police forces. When I arrived in Iraq, I made this a priority. We got local Iraqi police to come out on patrol with us, but we had to do it by force. Remember, at this time, the insurgents controlled the night. And working with us voluntarily was dangerous. Our rifles in their backs had to be their “life insurance” or else they’d have been killed that night by insurgents.

I always knew COIN was difficult. But I had no idea just how difficult it was until I tried to apply the principles myself. We know the principles work; people like Carter Malkasian, a courageous and intrepid State Department official, made them work in Helmand province, Afghanistan. The question isn’t does it work, but is it is worth the cost? It’s a fundamental question to consider, but it’s a political question that soldiers aren’t well placed to answer.

A common thread in your analysis is the role of political and military leadership having the same goal, of a realistic dialog between civil and military operators being a key to victory. What’s intriguing is that neither General Templer nor General Westmoreland were schooled in the experience of counter insurgency, and, by their record, had more or less conventional backgrounds. Why do you think Templer was able to not only inherit the troubles of Malaya in 1952, but reconfigure the operations to actually succeed in achieving Britain’s goals of a defeated insurgency and a domestic government en route to sufficiency, while Westmorland could not or would not do something similar in Vietnam?

Again, I think it’s healthy to consider context as well as individuals. Templer was a very thoughtful, perceptive, and keen minded man. While most of his wartime experience was, indeed, conventional, he’d also served in Palestine with its unique political, ethnic, and religious milieu. I think he had a broader range of thinking than Westmoreland. Westy was as conventional as it got, with next to no formal military education and certainly no serious study of COIN. He was a creature of his time, too, and was probably best suited to fighting in the Second World War.

The Parliamentary British system of government has created a more adaptable army than has the presidential American system.

There is of course a lot of scholarly debate about Westy’s role in Vietnam, and what might have unfolded if Creighton Abrahams had been selected first (see the work of Lewis Sorely and Mark Moyar). Abrams was also exceptionally experienced in conventional warfare, but had a more innovative intellect as demonstrated in his command of MACV.

Your title is taken from T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which was one of General Giap’s “bibles” for warfare in Vietnam, especially regarding leadership. What value do you think Lawrence has for understanding Vietnam and, perhaps, other insurgencies?

Training camp of the Malayan insurgents. Photo: IWM

Lawrence has many values, even if his own account of events is often historically suspect.

First and foremost, he wrote from the insurgent POV. Not many insurgents write memoirs. Many die in defeat, and even in victory those who succeed don’t have time for spreading their views and ideas, and some come from impoverished backgrounds and have no interest or ability to write about the experiences. Lawrence gave us an astonishing account of what it was like to fight an insurgency against a dominant power, and win. Another value is in how this romantic notion of the insurgent, his ideas and approaches, can captivate others. The appeal of insurgency can take root in popular opinion, and in today’s global media space, this cultivation of support for the underdog, romantic insurgent fighting against the dominant power is worth serious consideration. Countering the insurgent narrative is enormously difficult—like eating soup with a knife, you might say—and we haven’t been very effective at that battle of ideas at which Lawrence excelled.

Book review

In a little-known – “little-known” to lay readers like me, at least – military campaign, British forces were successful over a three-year period between1948 and1951 in turning back a Communist insurgency in the Federation of Malaya (still under the protection of Britain, Malaya would be become independent in 1957). In his outstanding book, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam, John Nagl revisits that campaign and shows us how young British officers were able to release the conventions of World War II and embrace a wholly different type of warfare. The British forces adapted, changed strategy, and were able “to defeat the guerillas at their own game by gaining the support of the local people.” In Vietnam, American forces were not able to so the same. This book tries to explain why, and the resulting lessons carry a powerful message for those of us who are not scholars of military history.

He concludes that the decisive factor was not logistics, not battlefield bravery, not any of the Nine Rules of War (MOOSEMUSS), but learning: “The U.S. Army was not as effective at learning as it should have been.” He finds that, while a handful of young British offices were alert enough to change that force’s approach, the U.S. Army “to a disturbing extent attempted to continue business as usual even when the old techniques no longer applied to the kind of enemy it faced.” The author interviewed both British veterans of the Malaya Emergency and American veterans from Vietnam, and clearly had open access to the archives.

Chapter One is entitled “How Armies Learn” and establishes the premise that success in war has as much to do with organizational theory as it does military science.

The essence of the American army … is ground combat by organized regular divisional units. Although the American army tolerates the existence of subcultures that do not directly to the essence of the organization, these peripheral organizations do not receive the support accorded to the core constituencies of armor, infantry, and artillery.

Part II of the book delves into the details of how this occurred. We read correspondence among the British as well as that of their enemy, the Chinese-influenced Malaya Communist Party (MCP). Part III, the author does the same with America’s much longer campaign in Vietnam (1950-72). In Part IV, he draws the comparisons between the two and emerges with a handful of hard-won lessons. Here is the first:

The Parliamentary British system of government has created a

more adaptable army than has the presidential American system.

A decade later, in that same subcontinent, America’s army was unable to adapt. Here is how he puts it (from Chapter Nine):

The organizational culture of the British Army allowed it to learn how to conduct a counterinsurgency campaign during the Malayan Emergency, whereas the organizational culture of the U.S. Army prevented a similar organizational learning process during and after the Vietnam War.

An army, Nagle argues, must be an adaptable organization: the army that is able to learn quickly is the army that wins the conflict.

He sets the stage for these two modern campaigns, going back to the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. Here is one of my favorite passages:

The American Civil War demonstrated the vast latent military potential of the United States. Falling as it did in the midst of the industrial revolution, the war was marked by the first use in combat of the railroad, the telegraph, and rifled repeating firearms. More importantly, it created and solidified the image of war as conventional battles between opposing mass armies …

One of his richest chapters is Chapter Two, “The Hard Lesson of Insurgency.” Here is how he begins the chapter:

Low-intensity conflict has been more common throughout the history of warfare than has conflict between nations represented by armies on a ‘conventional’ field of battle.

While conventional battles make for better stories, it may be that the more shapeless series of insurgencies are actually more telling. Here Nagl quotes the British military theorist Robert Thompson’s Five Principles of Counterinsurgency:

- The government must have a clear politic aim; to establish and maintain a free, independent and united country.

- The government must function in accordance with the law.

- The government must have an overall plan.

- The government must give priority to defeating the political subversion, not the guerillas.

- In the guerilla phase of an insurgency, a government must secure its base areas first.

In the course of his semi-epic narrative, Nagl hopes to demonstrate to his readers that war is not what it appears to be. While on the surface it is about combat force and strategic targets, underneath it is about culture and people. The surface explosions and the underlying struggle are linked, and the latter is by far more important. Here he quotes the British diplomat Oliver Lyttelton in his assessment of Britain’s chances in Malaya, 1951:

I summed up by saying that we could not win the war without the help of the population, and of the Chinese population in particular; we would not get the help of the population without at least beginning to win the war.

This simple advice can apply equally to America in Vietnam, Soviet Russia in Afghanistan, America in Iraq, and a half-dozen other asymmetrical engagements. Nagl also brings examples like T.E. Lawrence, his Seven Pillars, and his success in North Africa into the discussion.

This is not a book written for college students, but I recommend it to all college students, because you are going to be fighting in and paying for the next counterinsurgency (wherever it is). We all need to understand how this works. Difficult as this scholarly book may be for the general reader, this is necessary reading for all of us, especially the current generation of students. Western engagement in counterinsurgency looks to be a part of our future: the better we all understand it, the more successfully we can deal with as a nation. We do not want to continue applying the wrong resources and methods to the problem – trying to eat soup with a knife.

# # #

Excellent interview and book review!