How We See ‘The Other’ in Tintin

Emma Walker

The Role of Empire in One of Our Most Popular Comics

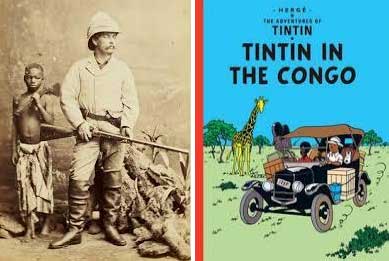

The explorer Henry Stanley in the Congo and a Tintin cover.

Editor’s Introduction

In 1879, King Leopold of Belgium hired a British explorer (Henry Stanley)

to build a series of roads across the lower Congo River region of Africa, and in so doing open the region’s wealth to the world. One hundred thirty-two years later, in 2011, a film about a Belgian boy named Tintin became a worldwide narrative, earning close to four hundred million dollars, earning a Golden Globe for Best Animated Feature Film, and the title of highest-grossing animated film in India’s history. The adventures of Tintin, featuring such titles as Tintin in the Congo and Tintin in Amerique, remain some of the most popular European comics of the modern age. A three-story museum, with nine exhibition rooms and a café, is dedicated to the comic book’s author.

What is the connection? How did the Belgian presence in sub-Saharan Africa spawn a story that would so dominate the global imagination a century later? As I often tell my students, you do not have to buy any of my ‘empire’ theory, but you do need to explain these stories, and what it is about them that endures so powerfully.

ABOUT THIS ESSAY

Emma Walker offers one answer in this revealing interview and original essay. Her viewpoint includes the idea that we see evidence in comics like Tintin of a dominant European narrative, “the romanticized and most crucially the false representation of Asia and the Middle East as subordinate.” Her thesis is that comics in general and Tintin in particular are valuable resources for cultural study. In studying them, we learn a great deal about colonial assumptions. The Author analyzes the art and text of specific Tintin adventures closely to prove her argument. She applies the work of scholars before her, such as Homi Bhabha and Paul Mountfort, to illuminate how the comic book adventures depict a world of harsh hierarchies. While the Author writes with scholarly detail, there is much a general reader (like me) can gain from her careful writings.

The point in all this is not that the work is evil, but that imperial attitudes can hide just beneath the surface of even our favorite, innocent-seeming stories, often in surprising ways. In this aspect, Tintin is in good company – we will see future postings about the changing Other appearing widely in children’s literature, from Peter Pan to Harry Potter to Binti, and in comics from Terry and the Pirates to The Avengers.

The museum dedicated to Tintin’s creator, Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi (Hergé).

One of author Emma Walker’s touchpoints is Edward Said, and a second is the important concept of ‘the Other.’ I recommend her article and interview as an introduction or platform to these two valuable ideas.

EDWARD SAID

The father of Orientalism, Edward Said is a scholar whom English teachers like me often refer to. His ideas about the stories we tell can be extremely useful to our students, especially because they spend so many hundreds of hours consuming narratives of all kinds. Said’s premise is that literature can be seen as a battlefield, with a dominant culture interpreting a “captured” culture any way it pleases. We tell stories to help explain how our society interacts with the world – in this way, all stories are “political.”

Here is one of his observations:

Every empire regularly tells itself and the world that it is unlike all other empires, and that it has a mission, certainly not to plunder and control, but to educate and liberate the peoples and places it rules directly or indirectly.

Said’s concept of Orientalism involves the often flawed lens through which Westerners view other cultures. An example is The Arabian Nights, told by a British author, featuring a romanticized Arabia that only exists in the mind of a Westerner. Students will find this a versatile idea – one that is applied to America’s foreign policy as well as the depiction of characters like The Mandarin and Electro.

THE OTHER

Of the many concepts I throw at my tired students in our ongoing attempt to jolt them into critical thinking and writing, “the Other” is always popular.

Students see the usefulness of “the Other” right away because we all spend so much time reading, watching, and telling stories – and we all know that certain characters are dealt a bad hand. Certain characters are portrayed as one-dimensional. They do not get backgrounds, flashbacks, or human motivations, or sympathetic characteristics of any kind. In monster movies it is the monster, in cowboy movies it is the Apache, in film noir it is often the pretty (but deadly) femme fatale.

Finally, I urge readers with an interest in these ideas to check out two articles in this online magazine, Patricia Kerslake’s provocative “Science Fiction and the Other” and Tabish Khair’s look at horror and the Other. We each must develop our own theories of literature as we consume and interpret these many narratives.

Milton Caniff’s “Terry and the Pirates,” another comic which plunged a Western protagonist into other cultures.

Interview with Emma Walker

September, 2019

What three ideas would you like a general reader to take away from your essay?

There are three main points that I would like the reader to take away from this essay. Firstly, I hope that the essay demonstrates that Hergé’s stories should be used as a historical source. As a piece of popular culture that harbours imperialist sentiments, The Adventures of Tintin are an indispensable source, not only for the Belgian narratives of national identity, but for the wider European narratives of empire. Secondly, I would like the reader to gain an understanding as to just how fantastically rich comic books are for the cultural historian. During the ‘cultural turn’ of the late twentieth century, very little attention appears to have been paid to comics, yet they provide us with much more information than we first suspect. Not only does the subject matter explore how identities have been forged through class, gender and nation but the prints, the colours, the cost and general material culture of the comic book, give us an insight into the lives of those who engaged with them. Finally, I wish for the essay to provoke the reader’s own thoughts regarding other literary sources which also reflect an imperial consciousness. The Adventures of Tintin, whilst predominantly Belgian in origin, have a reception that stretches much further than their own nation. In light of Edward Said’s notion of Orientalism, Hergé’s work should be given as much attention as other imperial texts, such as Kipling’s The White Man’s Burden or Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Paul Gravett writes that America’s caped superheroes don’t go over well in Japan, and that “Japan’s unlikely champions are mostly aliens and androids.” Does each culture give rise to particular comic-book heroes and heroines?

Gravett’s argument holds much validity, especially in light of the Tintin stories. Tintin as a character, very much embodies the West. For John Mackenzie, the heroes of imperialist literature were ‘male, had good looks and physical strength, were of good breeding and associated themselves with aristocrats’. It is entirely possible to also see Tintin in this way; he is after all a white, physically strong male, who is au fait with members of the aristocracy. Tintin demonstrates elements of the white man’s dominance; he is, to invoke the work of Nietzsche, an ‘ubermensch’-like figure. The strong, heroic reporter allowed readers to buy into the dominant ideology of the empire and in this sense; Tintin is an allegory for western power. He is a manifestation of the archetypal Western hero, created by Western culture.

Peter Pan is one of many children’s classics with imperial roots. Art by Mabel Lucie Pullman (circa 1929)

Can you recommend further reading — other works for students or general readers who are new to this topic?

The further reading that surrounds this topic is incredibly vast and varied. I would first start by recommending that you read other examples of imperialist fiction, for instance Albert Camus’ L’etranger, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness or Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Other examples of children’s fiction include On the World’s Roof by Douglas Duff. For those who want to further explore the empire on an academic level, I would highly recommended reading Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities, John Mackenzie’s Imperialism and Popular Culture, Kathryn Castle’s Britannia’s Children and Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks. The work of Catherine

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Hergé’s work should be given as much attention as other imperial texts, such as Kipling’s The White Man’s Burden or Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Hall and Simon Potter may also be of interest here. For those who may wish to explore the historiography of comic books in more depth, then the work of Jason Dittmer and Denis Gifford is of note. Further reading directly related to Tintin, includes Harry Thompson’s Hergé and his Creation, Tom McCarthy’s Tintin and the Secret of Literature and Paul Mountfort’s article entitled ‘Yellow Skin, Black Hair, Careful Tintin! Hergé and Orientalism’. This article can be found in the Australasian Journal of Popular Culture.

Is Tintin best seen as a product of its times? Would it be the same if it were created in the 2000’s?

Of course, like any primary source, one has to pay careful attention to the context and whilst The Adventures of Tintin remain popular today, when historically analysing them, one has to remember that they will always be a product of the twentieth century. As shown by some of the images included throughout this paper, it is clear to see why audiences of today perhaps wince, cringe or take a sharp intake of breath when faced with Hergé’s work. Undoubtedly, had the comic been created in the 2000’s, the lack of political correctness would have likely rendered them deeply unfashionable and unpopular. Yet, I feel it would be anachronistic to place the comics outside of the context that they were written in. The stories connote racial difference through stereotyped images of the empire. The characters offer the perfect opportunity to externalise the villain. They evidence the emergence of imperial nationalism and they represent an imperial world view made up of racial ideas. They are the product of an imperial context and must be seen as such.

For students considering for the first time a critical context of their favorite comics, is labeling Tintin “colonial” simply a matter of political correct-ness, or is it something deeper?

I think to disregard Hergé’s work as simply a matter of ‘political correctness’ would be doing a disservice to his stories. The Adventures of Tintin provide the historian with a specific cultural understanding of the empire; they are part of a larger structure of meaning. I think Hergé is much cleverer than we perhaps give him credit for. Particularly throughout Tintin in the Congo, Hergé’s clear use of irony sees the roles between noble and savage reversed. Whilst Tintin shows the Congolese citizens the benefits of Western progress, he himself degenerates into a savage hunter. It is actually Tintin who becomes the savage; the most civilised character ironically becomes the most animalistic. Hergé sophisticatedly caricature’s the Western presence in Africa, as one full of hypocrisy. Similarly, thorough his portrayal of the Thompson twins, Hergé actually satirises the falsehood of his stereotyped characters. Their often exaggerated and somewhat absurd outfits seek not to ridicule certain national identities, but instead mock the twin’s lack of cultural awareness.

You mention ‘Tintin in the Congo’ as a clear example of ‘Otherizing.’ Does Herge’s work change over the course of the Tintin run? Do his views change, or develop, over time?

I think particularly with Tintin in the Congo, the concept of ‘othering’ is made quite clear. The solid, black gradient used to depict the Congolese citizens as well as the binary oppositional language of ‘black’ and ‘white man’, creates a strict dichotomy between the two. However, contextually we must remember that Hergé never actually visited Africa; he only drew on a mass of newspaper and magazine cuttings, prospectuses lauding life in the

____________________________________________________________________________________

Hergé is much cleverer than we perhaps give him credit for … Hergé’s clear use of irony sees the roles between noble and savage reversed.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

colonial service and picture postcards galore. In his diaries, Hergé explains how he ‘was fed on the prejudices of the bourgeois society into which [he] moved…it was 1930. [He] only knew things about these countries that people said at the time and [he] portrayed these Africans according to such criteria, in the purely paternalistic spirit which existed in Belgium’. However, after his fourth instalment, Cigars of the Pharaoh, it becomes clear that Hergé’s work does begin to change; these binary distinctions become less clear. After meeting a promising sculpture student, Chang Chong-chen in 1934, Hergé came to appreciate the differences in foreign cultures. He discovered a fascination with Chinese poetry and writing and I think from The Blue Lotus onwards, we can begin to see a development in Herge’s views. Prejudices are somewhat swept aside and drawings become less caricatured. As I state in the essay, characters in The Blue Lotus are dressed in entirely western clothing and are made identifiable with the western world.

In her work ‘Breaking Barriers: Moving Beyond Orientalism in Comics Studies,’ Leah Misemer writes that “Orientalism, where manga are cast as the exoticized Other of American comic books, has been detrimental to the growth of comics in the U.S.”

What does that mean? Does it apply at all to Tintin?

I think Misemer has a very valid point. In fact, during the 1950s, many of the Tintin comics were found to be deeply unpopular within America. The Golden Books publishing house removed any content of inter-racial mixing and drunkenness from the comics, as it was deemed inappropriate for American audiences. Between 1966 and 1979, the Tintin comics were dropped by Golden Books and taken on by Children’s Digest. It was not long after 1979 that they were dropped for a second time and given to the Atlantic Monthly Press. Only six albums ever made it onto US soil and I think part of the reason why Tintin struggled to grasp an American audience, was due to issues surrounding translation. The publishers often used the British translation of the books, which included many words which were not known to the American people. However, another big reason behind America’s lack of interest in Tintin also boils down to precisely what Misemer discusses. Hergé’s fifteenth album, Land of Black Gold is still banned from the US today as it concerns itself with the issues of the oil crisis of the Middle-East, a topical issue where America is concerned. The work of Ziad Bentahar has analysed the reoccurring misrepresentation of the east through a western perspective. The albums pose a variety of questions concerned with the dichotomy between western and eastern cultures and identities. During the 1950s, there was a certain degree of western ignorance towards Asian culture and I think that there is perhaps a level of embarrassment present, that has prevented the stories from really taking hold in America.

‘Little white man getting too big’: Constructing the imperial ‘other’ in Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin

by Emma Walker

Edward Said’s text Orientalism has served as a key reference point throughout the examination of imperial history. His reading of the ‘East and ‘West’ dichotomy focuses on the romanticized and most crucially the false representation of Asia and the Middle East as subordinate, in order to justify the West’s colonial ambitions. As Said himself states ‘the Orient is the stage on which the whole of the East is confined…it appears to be a rather closed field, one that is primarily affixed to Europe’. In critiquing the narratives of Western dominance, Said undoubtedly allows for the discourse of imperialism to come under scrutiny. In his later work Culture and Imperialism, Said re-evaluates many of the key works that make up the Western literary canon. Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park for example, comes under much critical examination for its implicit acceptance of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. However, whilst the Tintin stories have been explored in depth by ‘Tintinologists’, they seem to have been neglected from the fields of cultural history, despite their fusion of colonial narratives and images. As a genre which rose to prominence during the twentieth century, the comic-book has often been seen as the ninth art, ‘enabling fixed images to develop through time by dividing events up into sequences of panels’. The interaction between image and text allows for certain dramatic and humorous possibilities, which has led to Hergé’s work often having been compared with the likes of Hogarth, in terms of their wit and empathy. Hergé’s signature technique known as ‘la ligne claire’ or ‘clear line’, added to the general admiration of Hergé’s fast-paced narratives, engaging characters and frequent comic interludes. Yet despite this, not only has the comic book generally been neglected from the studies of cultural history, but The Adventures of Tintin as a material interface, have also been disregarded. As Jason Dittmer has argued ‘comic books, like all popular culture, serve as political texts, shaping identities through language, both visual and textual.’ As a medium which relies on the combination of both image and text, it would seem that The Adventures of Tintin allow for distinct understandings of imperialism to come about. Despite the fact that according to Peter Mandler, ‘cultural history has become more sensitive to the presence of race and the discourses of power’, the narratives experienced in Tintin in the Congo and The Blue Lotus remain undoubtedly fixed by a predominantly paternalistic attitude towards Africa and the Orient. Whilst Tintin in the Congo focuses on Hergé’s portrayal of Belgian colonialism, The Blue Lotus remains closely connected to Said’s notion of Orientalism and thus both these stories can be used to illustrate imperialist ideology.

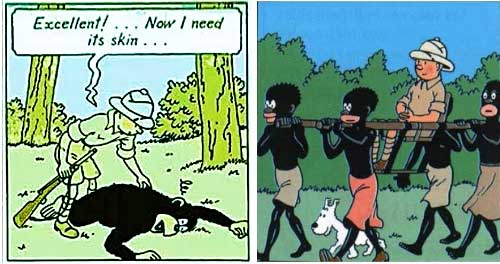

The reporter’s second adventure, Tintin in the Congo, began life in a serialised format, published in June 1930 as part of Le Petit Vingtième. Originally intended to promote the Belgian Congo, the story sees Tintin travel by steam-liner to Africa, where he engages in the trivial hunting of animals and several comic battles with the local civilians. Whilst there, Tintin takes it upon himself to rid the natives of the superstitious witchdoctor, bringing with him instead Western, rational medical thought, moral judgement and religious educational practices. The principal difficulty with the adventure is of course the subject matter.

As Michael Farr states ‘amidst a wealth of colonialist clichés, Tintin is left perilously close to the pale; politically he could hardly be less correct’. If this had been Tintin’s final adventure, it would have been rendered deeply unfashionable and simply forgotten about. However, despite the negative connotations that it conjures up for a twenty-first century audience, Tintin in the Congo can provide the cultural historian with a rich interpretation of nineteenth-century imperialist sentiments. One of the ways in which it does this is

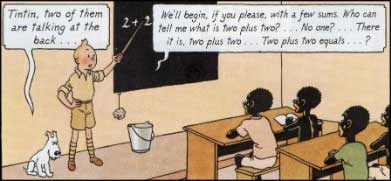

See figure 1.1 Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin: Tintin in the Congo (London, Egmont, 2011)

through Hergé’s colouring techniques, applied in the later 1946 edition. The African jungle for example, ‘has a greenness much more reminiscent of a European zoo than the parched, dusty expanses of the Congo’. This trope is one indicative of what Homi Bhabha terms ‘hybridity’, in which the mutual effects of the coloniser and the colonised are effectively fused together. Unlike Orientalism, for Bhabha, the construction of racial identity does not always conform to a binary distinction between the ‘orient’ and the ‘occident’, but instead takes place in a third space or an ‘in

__________________________________________________________________________________________

In return for their slave-driven efforts, Tintin shows them the benefits of Western progress.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

between’. What Bhabha suggests is that ‘the construction of a colonial subject and the exercise of colonial power through discourse, demands an articulation of forms of difference’. This ‘difference’ blurs categorical distinctions and thus in the image cited above, the African jungle appears to be a hybrid of both Congolese and Western cultures.

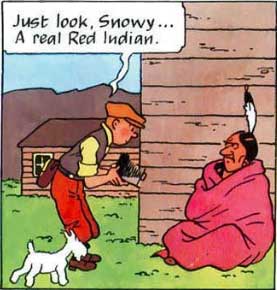

Moreover, throughout the entirety of the story, the African natives are caricatured as infantile and ignorant. This is perhaps aided by the solid, black gradient used to depict them, which in fact renders them similar to their primate ancestors. These changes in colour whilst subtle, nevertheless illustrate a desire to make ‘the dark continent’ more palatable to European audiences. This idea of taste is also manifested in Tintin’s rather paternalistic attitudes towards the Congo, reflected in the relationship between technology, knowledge and power. On arrival, Tintin declares that ‘these blacks are certainly nice to carry us to our hotel’. In return for their slave-driven efforts, Tintin shows them the benefits of Western progress. He acts as the doctor, the engineer, the peacemaker, the chief and even the teacher.

See figure 1.2 Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin: Tintin in the Congo (London, Egmont, 2011)

Not only does Tintin deliver a clearly patronising arithmetic lesson, but also in a later frame decides to teach the Congolese children the values of colonialism, through a geography lesson all about Belgium. As Frantz Fanon notes ‘a white man addressing a Negro behaves like an adult with a child and starts smirking, whispering, patronising’. There is of course a more poignant subtext at work here, in that Tintin is really teaching the Congolese the Western and more specifically the Belgian way. Ironically, Tintin, who is actually the ‘real’ foreigner of the tale, comes to stand for the white hero whom has saved Africa from its backward ways. The portrayal of the Africans as idle and superstitious clearly renders them as ‘other’ and at times animalistic. As Paul Landau crudely simplifies, Tintin in the Congo is ‘basically all to do with rubbery lips and heaps of dead animals’. In Jean de Brunhoff’s series Babar the Elephant, the real ‘other’ is of course Babar himself; as an animal, he exists in contrast to humans. As Stephen O’Harrow has argued by ‘dressing Babar in clothes and allowing him to become educated, he suddenly becomes as civilised as the Caucasian beings he mixes with.’ In essence, a very similar trope occurs throughout Tintin in the Congo. By showing them the benefits of Western progress, Tintin eliminates the animalistic behaviour that he sees within the Congolese citizens and through human intervention, fulfils his mission to civilise Africa. Through Hergé’s clear use of irony, the roles between noble and savage are reversed. Whilst Tintin shows the Congolese citizens the benefits of Western progress, he himself degenerates into a savage hunter. According to Beinhart and Hughes, ‘throughout history African culture has been viewed as one based upon pure savagery’. Yet Tintin actually becomes the savage; the most civilised character ironically becomes the most animalistic. Hergé rather sophisticatedly caricature’s the Western presence in Africa, as one full of hypocrisy.

See figure 1.3 ‘Snowball’ in Tintin in the Congo (London: Egmont, 2011)

When Tintin sees a Congolese carpenter enter the room with a saw, he mistakes him for a doctor. Once again, it is Tintin’s own lack of cultural awareness here that leads to his stereotyping of African doctors as savages, unaware of the correct surgical methods. This irony is furthered when Tintin names the carpenter, ‘Snowball’, an obviously degrading title given his clear, African heritage. Just as Tintin comes to symbolise the whole of Belgium, the Congolese figures encountered in Tintin in the Congo also symbolise the entirety of ‘the dark continent’. Tintin both physically and metaphorically embodies the West as ‘master of Africa’.

Said’s notion of ‘the other’, that is so evident in Tintin in the Congo, also becomes apparent in Tintin’s fifth adventure, The Blue Lotus. After being visited by an anonymous caller who warns him against Japanese businessman, Mr. Mitsuhirato, Tintin travels to Shanghai where he meets a secret society known as the Sons of the Dragon, who are devoted to combating the opium trade. For scholars such as Paul Mountfort, Hergé’s attempt to move away from racial prejudices remains largely unchallenged; ‘it cannot escape the clutches of Orientalism’. As Mountfort states, ‘The Blue Lotus is unable entirely to shake off an Orientalist gaze’, particularly with China being described as being populated by ‘vague, slit-eyed people, who would eat swallows’ nests, wear pig-tails and throw children into rivers’. Yet as Robert Bickers has argued ‘China has been constantly represented, misrepresented, and re-presented’ to the European reader.

See figure 1.4 ‘Mr. Mitsuhirato’ and ‘Professor Fang Hsi-ying’ in Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin: The Blue Lotus (London, Egmont, 2011)

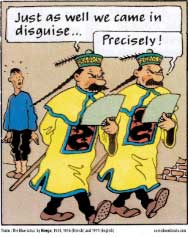

It becomes clear through the images cited above, that Hergé attempts to remove any preconceptions of the Chinese as evil and barbarous and instead places these stereotypes onto the Japanese. As portrayed in the drawing of Professor Fang, China suddenly becomes a place full of kind and wise citizens, whereas Mr. Mitsuhirato appears to embody the devilishly cunning ways of Japan. What Hergé makes clear throughout The Blue Lotus is the shift in perception towards the Japanese, wherein China became the victim of Japanese oppression. Hergé’s narrative is punctuated with all sorts of imagery that endeavours to make China palatable to a European audience, whilst simultaneously rendering the Japanese as ‘other’. The posters on the walls proclaim ‘down with imperialism!’ and the balding, middle-class Mr. Gibbons deems a Japanese rickshaw rider ‘yellow scum’. Whilst these images are made explicit throughout the album, Hergé sophisticatedly highlights, that there is a clear distinction between the hyper-asianisation of Japanese and Chinese stereotypes and that these ought to be distinguished between. The Thompson twins frequently demonstrate this satirisation throughout the remaining albums.

Their often exaggerated and somewhat absurd outfits seek not to ridicule certain national identities, but instead mock the twin’s lack of cultural awareness.

See figure 1.5 ‘Detectives Thompson and Thomson’ in Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin (London, Egmont, 2011)

The strategic placement of anti-imperialist, political slogans that condemn Japanese atrocities on the mainland, reveal a deeply-rooted fear of Japanese invasion, demonstrated in Hergé’s representation of Mitsuhirato as ‘villainous, pig-snouted and subhuman’. For Lasar- Robinson, ‘we can begin to see in The Blue Lotus the ‘de-asianisation’ of the Chinese versus the ‘hyper-asianisation’ of the Japanese’ and consequently, Japan becomes the embodiment of corruption, solely interested as a nation in maintaining commercial interests. By comparison to the Japanese characters, the Chinese figures are drawn relatively neutral and to a large extent are almost westernised, which has seen Hergé praised by the likes of Levi-Strauss for his ‘precision and ethnological accuracy’ within his characters. At the very beginning of the comic for example, a businessman from Shanghai comes to meet Tintin. Dressed in entirely western clothing, he is comfortably fitted into a paper-brown business suit and slacks; ‘the roundness of his face is not dissimilar to Tintin’s and is disrupted only by the dashed wrinkles on his forehead’. Distinguished from Tintin only by his eyes, Hergé has drawn the man in such a way that he is identifiable with the western world. Yet in selecting certain details, Hergé resists placing the man on an entirely western level, reiterating Bhabha’s hybridisation of racial difference. Chang however possesses the same eyes as Tintin. Standing next to each other, the two hardly look distinguishable, except for the strokes of black hair across Chang’s brow. Even Chang’s Chinese-style clothes do not draw away from his Tintin-like appearance. By identifying him with the hero of the piece, Hergé has solidified Chang in the reader’s western sympathies.

See figure 1.6 ‘Chang-Chong Chen in The Blue Lotus (London: Egmont, 2011)

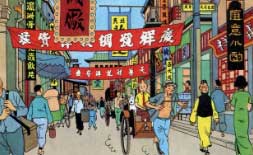

Through these subtle differences, Hergé instantly caricatures Japanese figures, whilst rendering the Chinese an innocent and hospitable nation. The scene in which Tintin takes a rickshaw through the streets of Shanghai, gives a clear historical snapshot of Chinese oppression, particularly given the crowded street and the rickshaw rider’s skeletal looking body. Tintin, the focal point of the image, has once again come to help save China from the Japanese ways; he is in a sense, what Robert Bickers’ terms a ‘Shanghailander’; that is to say he is the ultimate western man come to settle in Shanghai.

See figure 1.7 ‘The Streets of Shanghai’ in The Blue Lotus (London: Egmont, 2011)

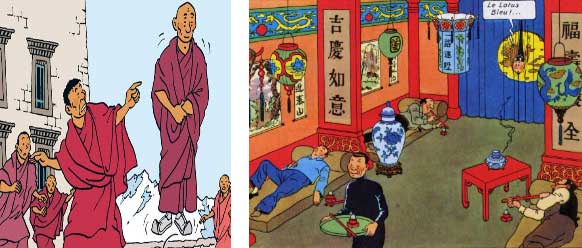

As a primary source, The Blue Lotus proves to be crucial in providing a perhaps more nuanced outlook on the western, cultural understandings of Asia. When used in tandem with a source such as Said’s Orientalism, The Adventures of Tintin can further question the Western ideology of the East. In Hergé’s later album Tintin in Tibet, not only does the reader become reintroduced to the character of Chang, but also encounters the wise and welcoming Tibetan tour guides and Buddhist monks. The way in which Hergé crafts the facial features of his Chinese and Tibetan characters in particular, connotes imagery of wisdom and kindness, something that is emphasised in their personalities; the Grand Abbot of Khor-Biyong for example, refers to Tintin as ‘Great Heart’ and wishes him ‘nothing but peace’.

See figure 1.8 ‘The Grand Abbot of Khor-Biyong’ in Tintin in Tibet and ‘The Blue Lotus’ in Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin: The Blue Lotus (London: Egmont, 2011)

According to Donald Lopez, ‘Tibetan Buddhism has long been the object of Western fantasy. The mysteries of their mountain homeland and the magic of their strange religion have had a particular hold on the western imagination’. Tintin in Tibet offers a fantastical gaze of the East. Almost Western in itself, it becomes as Kora Caplan states, part of the ‘imaginative literature of the empire’. Furthermore, the frequently placed Chinese vases throughout The Blue Lotus are emblematic of the growing demand for chinoiserie during the late eighteenth century. For Stacey Sloboda, in small doses chinoiserie began to permeate Western culture as being a tasteful commodity, particularly for the emergent middling and professional classes. The luscious colours and glossy enamel work allowed for a visual appreciation of Asian culture, one which was very much centred on the notion of politeness. By placing these cultural signifiers throughout the episode, Hergé undoubtedly calls for an ‘occidentalisation’ of Asia.

This essay has explored how Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin should be considered as part of the cultural and textual medium that reflects imperial consciousness. Undoubtedly, there is a certain element of Hergé’s stories which demonstrate this culture of imperialism and thus as a source, The Adventures of Tintin can be described as a vehicle which conveys imperialist sentiments. Jacqueline Bratton, in her study of Victorian children’s literature, has argued that ‘the imperial ethos can be found in much of the literature which was not overtly imperial in setting’. Even if one was to take The Adventures of Tintin at face value, the ideology of the empire would still remain throughout the albums. Popular literary culture such as The White Man’s Burden or Heart of Darkness, have glorified the aims of imperialism and it seems after much analysis that The Adventures of Tintin is no different. In light of Said’s notion of Orientalism, it has been made clear that whilst Tintin in the Congo re-affirms ‘the dark continent’ as ‘lazy, barbaric and other’, The Blue Lotus does much to challenge the western, colonial ideologies of the Orient.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

‘Comic books, like all popular culture, serve as political texts, shaping identities through language, both visual and textual.’

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

1 For examples see Potter, Simon British Imperial History (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); Lee, Stephen Imperial Germany 1871-1918 (London: Routledge, 1998); Hutchinson, John Late Imperial Russia 1890-1917 (Harlow: Longman, 1999) .

2 Said, Edward, Orientalism (London: Penguin, 2006) *Note the work was first published in 1978.

3 Said, Orientalism, pg. 63

4 See Said, Edward Culture and Imperialism (London: Vintage, 1994)

5 For examples see Denis Gifford, The International Book of Comics, (London: Hamlyn, 1984); Paul Gravett and Peter Stanbury, Great British Comics: Celebrating a Century of Ripping Yarns and Wizard Wheezes, (London: Aurum Press, 2006)

6 Grove, Laurence ‘Bande Dessinee Studies’ French Studies 68:1 (2014) pp. 78-87

7 ‘Artist Ed Gray and the Hogarth Collection with Dr. Martens’ (October, 2015) available via The Sir John Soane’s Museum. Accessed via: https://www.soane.org/features/artist-ed-gray-and-hogarth-collection-dr-martens, Date accessed: 21/03/2019

8 See, for example, Denis Gifford, The International Book of Comics, (London: Hamlyn, 1984); Paul Gravett and Peter Stanbury, Great British Comics: Celebrating a Century of Ripping Yarns and Wizard Wheezes, (London: Aurum Press, 2006); Graham Kibble-White, The Ultimate Book of British Comics, (London: Allison & Busby, 2005); and George Khoury, ed., True Brit: A Celebration of the Great Comic Book Artists of the UK, (Raleigh, NC: TwoMorrows Publishing, 2004). See also Darren Davies’ British Comics website http://www.britishcomics.com Date accessed: 28/02/2019. It is worth noting that there have been some attempts to rectify this, such as Michael Rothberg’s study of Art Spiegelman’s comic Maus. As a visual representation of Spiegelman’s interviews with his father Vladek, Maus depicts the story of Vladek’s survival through the Holocaust as a Polish Jew. For Rothberg, Spiegelman reinvigorated the comic book medium as a viable form for both the narrative and visual means for historical representation to come into being. See Rothberg, Michael “We Were Talking Jewish”: Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” as “Holocaust” Production’ Contemporary Literature, Vol. 35, No. 4 (1994), pp. 661-687

9 Dittmer, Jason Comic Book Geographies (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2014) pg. 251

10 Mandler, Peter ‘The Problem with Cultural History’ Cultural and Social History, (2004) 1:1, pp. 94-117, pg. 94

11 Farr, Tintin: The Complete Companion pg. 21

12 Farr, Tintin: The Complete Companion pg. 22

13 Farr, Tintin: The Complete Companion, pg. 21

14 Bhabha, Homi ‘Signs taken for Wonders’ in Rivkin, Julie and Ryan, Michael Literary Theory: An Anthology (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004) pg. 1175

15 Bhabha, ‘Signs taken for Wonders’, pg. 1175

16 Hergé, The Adventures of Tintin: Tintin in the Congo (London, Egmont, 2011) pg. 38

17 Hergé, Tintin in the Congo, pg. 65

18 Fanon, Frantz Black Skin, White Masks (London: Pluto Press, 1986) pg. 31

19 Landau, Paul Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa (California: California University Press, 2002) pg. 91

20 O’Harrow, Stephen ‘Babar and the Mission Civilisatrice: Colonialism and the Biography of a Mythical Elephant’ Biography, 22: 1 (1999), pp. 86-103

21 Beinhart and Hughes, Empire and Environment, pg. 63

22 Apostolides, Jean-Marie The Metamorphosis of Tintin or Tintin for Adults (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010) pg. 14

23 Mountfort, Paul ‘Yellow Skin, Black Hair, Careful Tintin! Hergé and Orientalism’ Australasian Journal of Popular Culture 1:1 (2001) pp. 33-49, pg. 47

24 Mountfort, ‘Yellow Skin, Black Hair, Careful Tintin’, pg. 33; Hergé, The Blue Lotus pg. 43

25 Bickers, Robert ‘British Travel Writing from China in the Nineteenth Century’ Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 54:1 (2011) pp. 781-789, pg. 784

26 Hergé, The Blue Lotus, pg. 7

27 It is worth noting that many scholars of Orientalism do not make clear the distinction between Asian groups. For instance, see Macfie, A. L. Orientalism: A Reader (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000); Sardar, Ziauddin Orientalism (Buckingham: Open University Press, 1989); Panikkar, K.M Asia and Western Dominance (Kuala Lumpur: Other Press, 1993)

28 Mountfort, ‘Yellow Skin, Black Hair, Careful Tintin!’, pg. 41

29 Lasar-Robinson, Alexander ‘An Analysis of Hergé’s Portrayal of Various Racial Groups in The Adventures of Tintin: The Blue Lotus’ pg. 6 available online, accessed via: https://www.tintinologist.org/articles/analysis-bluelotus.pdf. Date accessed: 21/03/2019

30 Levi-Strauss in Tisseron, Serge and Harshav, Barbara ‘Family secrets and social memory in “Les Adventures de Tintin”’, Yale French Studies, 102:1 (2002) pp. 145−59, pg. 145

31 Lasar-Robinson, Alexander ‘An Analysis of Hergé’s Portrayal of Various Racial Groups in The Adventures of Tintin: The Blue Lotus’, pg. 8

32 Lasar-Robinson, Alexander ‘An Analysis of Hergé’s Portrayal of Various Racial Groups in The Adventures of Tintin: The Blue Lotus’, pg. 8

33 Bickers, Robert ‘Shanghailanders: The Formation and Identity of the British Settler Community in Shanghai 1843-1937’ Past and Present, 159: 1 (1998) pp. 161-211

34 Hergé, Tintin in Tibet (London: Egmont, 2011) pg. 181

35 Lopez Jr, Donald S. Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West (University of Chicago Press, 2012) pg. 3

36 Kaplan, Cora ‘Imagining Empire: history, fantasy and literature’ in Rose, Sonya O; Hall, Catherine At Home with the Empire: Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006) pp.194-212, pg. 201

37 Sloboda, S. ‘Buying China: Commerce, Taste and Materialism’ in Chinoiserie: Commerce and Critical Ornament in Eighteenth-Century Britain. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), pp. 59-107.

38 Bratton, Jacqueline The Impact of Victorian Children’s Literature (London: Routledge, 2015) pg. 15

# # #