How Stanley Kubrick Lost His Way

Kubrick and the Rule of Empire

By Tom Durwood

Stanley Kubrick circa 1949. LOOK Magazine Collection, Library of Congress

An English teacher’s “empire theory of literature” sheds a little light on the colossus of filmmakers.

ONE: EMPIRE THEORY

We have applied my theory of empire to John Ford and his successors Ridley Scott, Clint Eastwood, Steven Spielberg, and Robert Redford (see “John Ford’s Heirs” in Empire Studies Magazine https://empirestudies.com/john-fords-heirs). We found, among other things, that:

a) while they are all drawn to High Empire war and combat at some point, John Ford thereafter takes an almost exclusive interest in Roots of Empire and Rising Empire stories. He and Eastwood blank on the Stage Four: Corrupt Empire themes which Spielberg and Ridley Scott find so compelling.

b) underlying commonalities can be found between films as different on their surfaces as The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence, Flags of Our Fathers, and Downhill Racer (mythmaking in High Empire)

c) Ford and all his heirs make at least one film that explicitly rejects an imperial depiction of the Other (Cheyenne Autumn, Letters from Iwo Jima, Jeremiah Johnson, The Color Purple, American Gangster)

d) Spielberg tends to tell the imperial version, the oft-told version (Lincoln, Saving Private Ryan), while Ford prefers the lesser-known folk version (Young Mr. Lincoln, The Searchers).

_________________________________________________________________________

We are at a point in our work when we can no longer ignore empires and the imperial context in our studies. – Edward Said

_________________________________________________________________________

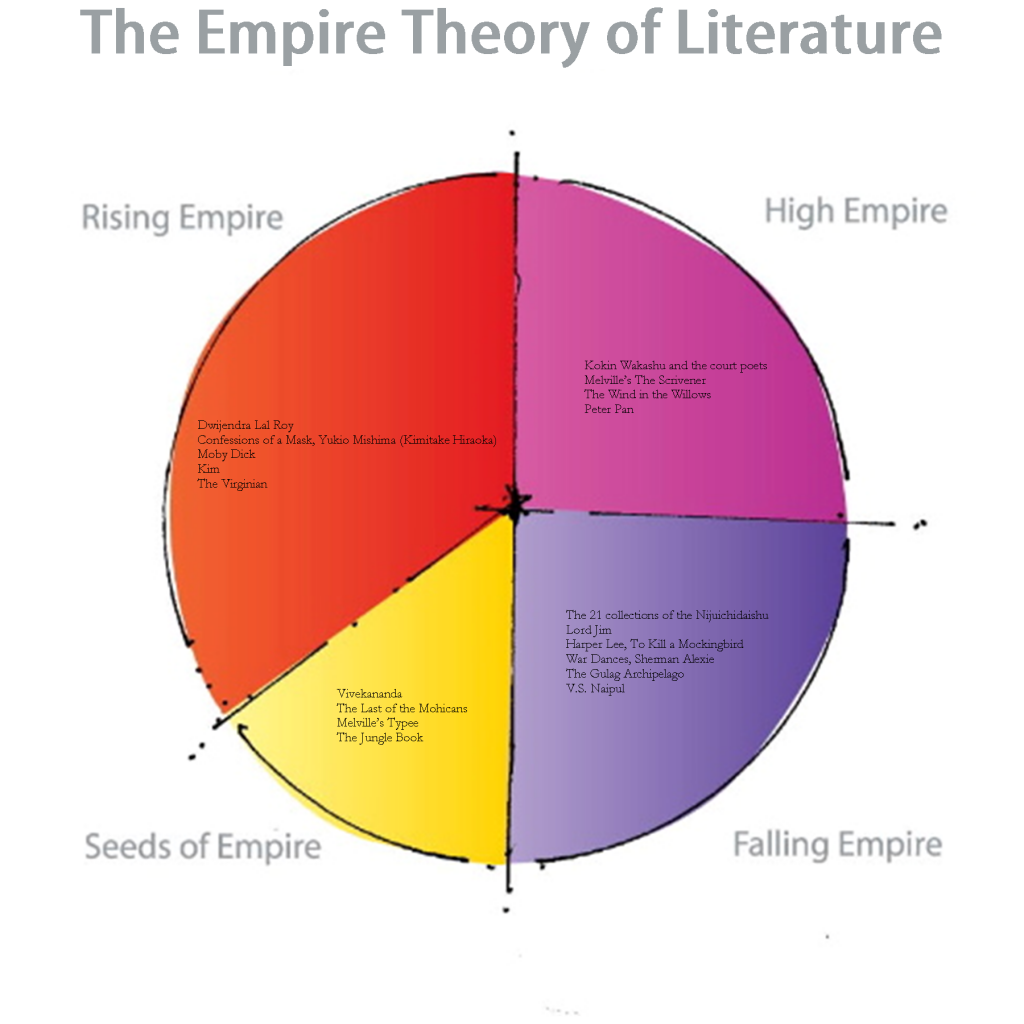

There are three tenets of my empire theory of literature:

One, all stories are political. All stories take an inherent or an explicit viewpoint on the existence of empire. Romantic comedies are all imperial, for example, and revel in the wonder of High Empire food, cars, architecture, cell phones and modern manners. Monster movies tend to be counter-imperial, disinterring buried traumas, asking angry questions about how we organize society.

Two, that every story is anchored in one of the four stages of empire (Roots, Rising, High, and Failing – see chart below). Robinson Crusoe is a rare Stage One: Roots of Empire story. Dystopian literature is all Stage Four: Failed Empire.

Three, that the success and longevity of a story depends on how well it engages with the processes of empire. Moby Dick ranks extremely high on this third metric, while Waiting for Godot ranks extremely low.

You begin to see the theory’s limitations.

Here is how Kubrick’s work pans out on my matrix:

ROOTS OF EMPIRE (two cultures meet)

“Dawn of Man” prelude to 2001: A Space Odyssey

RISING EMPIRE (one culture takes dominance)

Spartacus

Early sections of the unmade Napoleon film

HIGH EMPIRE (enjoying the rewards of empire while clashing with other H.E.’s)

Paths of Glory

Barry Lyndon

Dr. Strangelove

Lolita

Full Metal Jacket

FAILED EMPIRE (We Blew It)

A Clockwork Orange

2001: A Space Odyssey

The Shining

Eyes Wide Shut

AI (screenplay only)

Unlike John Ford and Steven Spielberg, Kubrick has little or no interest in early empire, especially American nation-building. Stages One and Two bore him, as does the American nation in general. He is an American with a European gaze.

* * *

Frank Gehry is an imperial architect. He is mostly hired by museums and large corporations. Rich people can admire his work. Sam Mockbee, in the other hand, is a folk architect, designing houses and baseball parks for the working classes.

A question for us to consider is whether SK is a filmmaker who tells the imperial side of the story, or one who depicts the folk side. Was SK an imperialist? Whose side did he take? Does it matter?

The answers are Yes, the Aristocracy’s, and Yes.

While SK infrequently depict s the bottom of the social pyramid, one always suspects his heart is with the ruling classes. Little Alex and Barry Lyndon and Spartacus are all working-class characters, yes, but these are working- class depictions in the same way Julia Roberts is a depiction of a streetwalker in Pretty Woman. These are depictions of elites in disguise. The learned Humbert Humbert, all of the characters played by Peter Sellers in Dr. Strangelove, Manhattanites Bill and Alice Harford of Eyes Wide Shut – these are all aristocrats, if flawed, or in disguise. Brooklyn-born Stanley Kubrick certainly seems to take real delight in the settings of the high-born – the French courtroom of Paths of Glory, the elegant, green-trimmed, glass-floored crystal bedroom at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the cathedral-like hall for secret-society masked gatherings in Eyes Wide Shut, United Nations boardrooms, NASA outer-space stations.

_________________________________________________________________________

Walter Benjamin urges us to “connect an artwork to the larger system in which it operates.” Stanley Kubrick (SK) operates in the system of modern empire. Let’s see where he lands.

_________________________________________________________________________

Minority figures are rarely spotted in SK’s works. Exceptions here include Eightball in Full Metal Jacket and Dick Halloran in The Shining. For the most part, SK protagonists are high-ranking white men (professors, politicians, doctors, astronauts, writers, military officers) tortured by some insidious trap of empire, acting in opposition to an unnamed faction of society.

Women are equally hard to spot. Low points for realistic depictions of females of any age or station, Nicole Kidman and Christiana Harlan being exceptions.

Paths of Glory is a total win for my little theory. It is so good precisely because it dwells on how an empire operates on the axis of justice. The girl singing in a café at the ending is heartbreaking because nations are fools, because the rise and fall of empire is heartbreaking. This most compelling war movie appears to be Stage Three: High Empire but it is actually Stage Four: Empire’s Failure in disguise. Certainly, that is where SK’s heart lies, as we will soon see.

While Spartacus is tainted for our purposes, since SK had limited creative control over it, still it is a direct hit on Stage Two: Rising Empire. This is a pure Stage Two work, and all its attention, all its meaning has to do with class conflict and the fractured processes of empire. The care taken to depict a “realistic” gladiator school compares in a small way to the care Melville gives to the processes of whaling. I am placing “realistic” in quotes because the reality is an invented one, just as the Dr. Strangelove war-room set is “realistic.”

Spartacus makes me look smart.

Not so Lolita, a film off of which my theory bounces. Lolita has little to do with empire, that little being a passing observation about class. When Humbert visits Lo in a trailer-park type setting, at the end, it is somehow more telling, more tragic (at least to SK) that she is happy with not with another aristocrat but with working-class Richard Schiller.

2001: A Space Odyssey is the trophy piece of our consideration. It is exactly and completely about the rise and fall of the human empire. It begins with a rare authentic Stage One passage about the Roots of Empire, where two cultures meet for the first time, and one begins to show dominance. Booyah!

The film’s Jupiter section is riddled with thoughtful, almost exquisite detail as to how things work, how food is served in anti-gravity, how astronauts exercise, how long the air-chambers take, on and on. The larger themes of fall from grace and rebirth only work because the setting s and processes and people of the empire are so well-crafted by SK.

A Clockwork Orange is of course about empire, but only secondarily so. It is set in a world arriving after the clash of empires, in an Orwellian version of England where the Soviet Empire has apparently won sway. That regime now seeks to control its populace.

“Spartacus” poster (Universal International, 1960)

TWO: HOW ACCURATELY SK PORTRAYS EMPIRE

Let’s look at SK in light of my Rule Three — the accuracy of his depictions of empire’s inner workings.

Paths of Glory gets high marks in this regard. I believe SK knows how a French courtroom works. When his camera moves through the grim trenches, I’m in. I’m believing every second.

Dr. Strangelove and Full Metal Jacket also get high marks. I believe the director knows how the cockpit of a bomber works. How members of the military walk and talk, battlefield actions, the equipment and procedures of long-range aircraft — these get my 100% buy-in.

2001: A Space Odyssey. Check. I believe SK knows how a spaceship works.

However, when we come to Eyes Wide Shut, I call BS.

I don’t think that is how a doctor’s office works. I don’t think that is how a marriage works. I don’t believe that is how aristocratic swingers arrange their get-togethers, even in Europe. It’s all stilted, painfully mannered. It’s all forced. It’s all phony.

A smart critic like Nathan Abrams might argue that this divergence from a coherent reality is a neutral thing, that SK ignored the actual world in favor of his poetics. My answer: re-watch Eyes Wide Shut. The negative impact of this debacle of a movie is, to me, extensive as we reconsider this great filmmaker. If Eyes Wide Shut represents SK’s vision, it is clear that his values had somehow turned in on themselves.

Me calling a Kubrick film a ‘debacle’ — this would be the right time for me to come clean. I have no filmmaking skills beyond several decent home movies of my kids’ volleyball and basketball games. Me lowering the boom on SK is beyond ludicrous.

Yet I do feel fully entitled to explore what makes his movies tick.

“2001: A Space Odyssey” (MGM, 1968). Poster illustration by Robert McCall.

Here, I believe, is what SK wanted all along: Empire’s Failure. It is a theme or an attitude hinted at in earlier films and made explicit in 2001:A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut AI, and to a lesser degree, The Shining. All of these films land squarely in Stage Four: Empire’s Failure and carry the following themes:

Empire is Doomed by Internal Rot

We Are All Cruel Maniacs. (A Clockwork Orange, Full Metal Jacket, Barry Lyndon)

Power Corrupts. (Dr. Strangelove, Lolita)

Base Instincts Win. (The Shining, Eyes Wide Shut, Lolita)

Humankind Deserves Extinction (2001: A Space Odyssey, possibly AI)

THREE: KUBRICK’S OWN EMPIRE AND A TURN FOR THE WORSE

Let’s look at the pivotal moment of the relationship between SK and empire: namely, when he began building his own empire. The turning point for SK comes after 1971’s A Clockwork Orange and before Barry Lydon in 1975.

Sheri Linden, for The Hollywood Reporter (April 2020), writes that:

Composer Leonard Rosenman confesses to having grabbed the filmmaker by the neck after he and his orchestra were called upon to do 105 takes of a piece of music for Barry Lyndon, noting wryly that “the second take was perfect.”

And that, “In pursuit of his idea of perfection, [ SK] bewildered and frustrated many of his creative collaborators.” In other words, he ignored the wishes and opinions of his collaborators. He was now Emperor, and he had the power to do so.

Adam Baldwin, an actor featured in Full Metal Jacket recounts, “We were a group of green actors mostly. He had his own private little war going on there. He didn’t have a lot of respect for any of us.

“There was one scene where we were sitting on a wall and the tanks are firing off in the distance. We ended up doing that for three and a half weeks — one scene.”

For two years, Full Metal Jacket actor Tim Colcieri worked on his scenes as Gunny Sergeant Hartman were ready to film. He memorized dialogue endlessly. All this time on call, Colcieri turned down all other work in deference to SK … until SK changed his mind and gave the part instead to one of the film’s technical advisors. Losing that role redefined Colceri’s life, and not for the good. “I’m still suffering from it,” he told The Hollywood Reporter in 2019. “It will never end.”

“The cast had other jobs lined up and had to juggle,” writes Michael Herr, who worked with SK on Full Metal Jacket. “Vincent D’Onofrio had gained 40 or 50 pounds to play Leonard, and he had to keep it on through all those idle months.”

SK had built his own empire.

SK had acquired an imperial disregard for other people’s time.

He had also acquired a global network of movie technicians and exhibitors. Steve Southgate, Vice President in charge of European technical operations for Warner Brothers, recalled SK’s internationals reach in a 1999 interview with The New York Times:

He was one person in the film industry who knew how the film industry worked — in every country in the world. He knew all of the dubbing people, the dubbing directors, the actors, he had relationships with foreign directors who would supervise his work because he couldn’t be there to supervise himself. We had to go around to every cinema to make sure the projection lights were right, the sound was correct, the ratios were right, the screens were clean.

_________________________________________________________________________

He ignored the wishes of his collaborators. He was now Emperor, and he had the power to do things his way.

_________________________________________________________________________

Early Kubrick depended on strong collaborators (Douglas Trumbull, Terry Southern) and actors (Peter Sellers, George C. Scott) to make their own substantial contributions to his films. Later, in his imperial phase, not so much. As he became more powerful, SK walked alone. His collaborators had less influence on him and his work. Ask Michael Herr. Ask Stephen King. The films suffer for it.

Ryan O’Neal was certainly personable and effective in Paper Moon. It is not his fault that he was miscast as the anti-hero of Barry Lyndon. SK’s cool visuals require strong acting as a counter-balance. He needs Peter Sellers and George C. Scott in the same way Spielberg needs the warmth and likeability of Richard Dreyfuss, Robert Shaw and Roy Scheider in Jaws. Even a single scene – such as the ‘USS Indianapolis’ scene with these three — brings a ripple of human depth to the entire story. On a likeability scale of 1 to 10, the characters in Barry Lyndon score around a Negative 200.

After the first day’s rushes, why did no one tell SK that this wasn’t working?

Because no one crosses the Emperor. Kubrick had crossed over into Oz, the zone of believing your own PR. “When he found out that he was smart and successful and all that, then it went the other way — everything had to be grand,” as composer and Kubrick collaborator Gerald Fried puts it. “It was as if his success gave him permission to let his fears predominate.”

_________________________________________________________________________

Kubrick began as the Spartacus of Hollywood. He became the Humbert Humbert.

_________________________________________________________________________

By the time of Full Metal Jacket, SK had also acquired an imperial disregard for story.

The art critic Clement Greenberg wrote that the artist seeks to achieve a mastery of his medium, so that he or she is able to liberate a work from “any narrative, or mimicry, or the need to bear in itself any content other than the purely aesthetic…” That is, any trappings of chasing illusional plot and theme for the sake of story are to be dropped, thus proclaiming the primacy of pure form. Louis L’Amour: out. Agatha Christie: out. No one cares about the false melodramatic feelings aroused by your bogus “narratives.”

Well, all I can say, Clement, is that this approach worked very, very well for SK in 2001: A Space Odyssey. It did not work in Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut. The mix was off. SK is of course welcome to abandon traditional narrative structure. But he (and his audience) pays a price for that decision.

He left the shores of character, motivation and the three-act structure behind, but he never landed anywhere. Barry Lyndon is just shoddy storytelling, no matter how clever the SK apologists’ arguments.

* * *

Let us now submit a Filmmaker’s Rule of Empire: Do not expand your sphere of influence needlessly. I made it up.

Let’s apply it to Stanley Kubrick and see what we get. We get seventy takes of Sidney Pollack opening a door. We get squadrons of assistants carrying around glass jars of soil. We get a closet full of blue blazers and white turtleneck sweaters. We get Eyes Wide Shut.

_________________________________________________________________________

Stanley was the Big Fisherman. He played everybody like a fish … It really was Stanley’s feeling that it was a privilege to be working with him. — Michael Herr

_________________________________________________________________________

As his career progressed, Kubrick broadened his span of control in the real world and lost focus in his cinematic world. He thus became of a victim of his own imperial trappings. It is right there on screen to see.

FOUR: COUNTER ARGUMENTS

1) Tom, you apparently do not have the mental capacity to understand SK’s true aspirations. Your lowbrow “theory” is almost meaningless, a shack before the monumental architecture of SK’s advanced talent and looming exactitude.

Also, why don’t you mention “The Killing” and “Fear and Desire” and “Killer’s Kiss” in your breakdowns?

2) Tom, if you had done your research, you would know that SK worked with a small and efficient crew. He delivered his films under budget. Therefore, the excesses you ascribe to him are not exactly of Heaven’s Gate proportions, are they?

3) Many smart people seem to actually enjoy Barry Lyndon.

William Hogarth painting from the era of ‘Barry Lyndon’

FIVE: A SIMILAR TREND AMONG SK’S NEPHEWS

Three of Stanley Kubrick’s filmmaking kin — George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg — also broke the dreaded Filmmaker’s Rule of Empire. Two of them succumbed, as did SK.

Along the Roman Empire model, Francis Ford Coppola can represent the dangers of excess. After his great success with the remarkable first two Godfather films, he expanded his real-world holdings to included Zoetrope Studios, two wineries, a brand of pasta sauce, a literary magazine, and the Blancaneaux resort hotel in the Maya Mountains of Belize.

_________________________________________________________________________

Coppola had his chartered airliner deliver fresh pasta from Italy for cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and his Italian cameramen. (Alison Nastasi, Flavorwire)

_________________________________________________________________________

As Eleanor Coppola’s detailed in her 1979 memoir, Notes on the Making of Apocalypse Now, no one was there to curb the director’s imperial whims. “We had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little, we went insane,” Coppola himself has reportedly remarked. Even worse, he broke a cardinal rule of good film-making – starting to film without a complete script. He eventually surrendered artistic control to his lead actor, Marlon Brando.

If Zoetrope was the Roman Empire, done in by internal corruption, then Lucas was the British Empire – stretched too thin. Britain’s resources and focus were cast too wide when it tried to govern in five continents plus Ireland and Scotland (as well as conducting wars with Spain, France and the Netherlands). Doing right in America, India, and Australia simultaneously proved impossible. So too was Lucasfilm stretched thin by ILM, Pixar, real estate (Skywalker Ranch), Howard the Duck and divorce. Hung with his own rope, Lucas was betrayed by his admirable stubbornness, to the point that he was forced to make the ill-considered second trio of Star Wars movies in order to save the Lucasfilm empire.

_________________________________________________________________________

Lucas became what he once reviled: the corporate chieftain of a company for which scale and sparkle and box office numbers trumped the specifics of his artistic vision. (Dale M. Pollock)

_________________________________________________________________________

Spielberg’s undeclared empire has survived, as has the undeclared American empire – commercially savvy, adaptive, and pretending it is not an empire. Spielberg’s filmmaking has not suffered, as the others’ have, as we know from the lean, near-perfect “The Post” (2016).

“Apocalypse Now” (United Artists, 1979)

_________________________________________________________________________

If Zoetrope was the Roman Empire, done in by internal corruption, then Lucasfilm was the British Empire – stretched too thin.

_________________________________________________________________________

SIX: MISCELLANY

If you still doubt my premise of a sharp SK decline, watch the last five minutes of Paths of Glory and then watch any five minutes of Eyes Wide Shut:

The hero of Spartacus is Kirk Douglas, movie star.

The hero of Saving Private Ryan is Captain Miller.

The hero of Full Metal Jacket is Stanley Kubrick’s Filmmaking.

Kubrick began as the Spartacus of Hollywood. He became the Humbert Humbert.

Is Eyes Wide Shut as bad as Dr. Strangelove is good?

Yes.

Do the flaws of Kubrick’s flawed-by-imperial-thinking films outweigh the virtues of the single film 2001: A Space Odyssey?

No.

Other theories of SK detail cracks in the Kubrick Museum walls. Amy Roberts, writing in Film View, holds that women are little more than props to SK. In a 2013 interview with BBC, Stephen King described Kubrick’s version of Wendy Torrance as “One of the most misogynistic characters ever put on film. She is basically just there to scream and be stupid and that’s not the woman that I wrote about.” Elsewhere, King goes on to call The Shining “an empty Cadillac.”

The movie that SK did not make reveals something. Napoleon would have lent him the story structure and emotional core that peasants like me so badly miss in Barry Lyndon. In Napoleon, SK would have gained access to the military spectacle, rich imperial trappings, and irony, all filmed in special light with the special lenses. Barry Lyndon should have been Napoleon, an epic which at least had a clear rise and fall.

The Outlook Hotel is a reliquary of High Empire (in the case, the Roaring 20’s) and Jack Torrance is a working-class caretaker among ghosts of the ruling class. Except that he is not. Working-class, that is. By casting Jack Nicholson, whom the audience recognizes as singularly smart, funny and charming, SK reverts to a familiar type: aristocratic white males tortured by their own desires and inner conflicts in High Empire-turning-to-Failed Empire settings.

With respect to my empire theory grid, Kubrick’s imperial dance card is incomplete. What is missing is the building of America. To a John Ford and William Wyler fan like me, he should have broadened his scope and looked at the topics and themes of Stage Two.

SEVEN: CONCLUSION

This argument of mine is, of course, absurdly reductive, but there may be some value in adding the concept of empire to the mix in our appreciation of

Stanley Kubrick and his most excellent works.

Walter Benjamin urged us to “connect an artwork to the larger system in which it operates.” SK operates in the system of modern empire, its purveyors, its dynamics, its evolutions, its rules and languages, its unintended consequences, its outcasts and its bitter ironies. He was brilliant in his depiction of empire. Once he entered the apparatus of his own empire, things changed. Later in his career, he himself got caught up in imperial aspirations.

We can hold two disparate ideas on our heads: that SK was a most compelling director, and that he was flawed. None of this detracts from his achievements. He is the finest of our filmmakers — still, yet, and always.

Stanley Kubrick, Tony Curtis and Laurence Oliver on the set of “Spartacus”

(1960) Wikimedia Commons

###