Herman Melville, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and U.S. Empire

Literature in the Context of Politics:Herman Melville, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and U.S. Empire by Jeffrey Hole

Editor’s Introduction

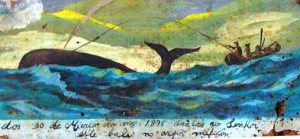

Color study for Portuguese fresco, Ponta Del Negro. The whale hunt in Moby Dick took on aspects of the slave hunt.

While every work of art stands on its own, it is always interesting to tuck it into the particular context in which it was created, both historical and personal. One example I often use with my cadets (during our study unit on heroes) is that Jerry Schuster, who invented Superman, was a child of an immigrant family – far from home, with a new name in a strange new land, without a strong identity, helpless against new forms of evil — and the story he created reflected all this. The Superman character became his wish fulfillment, a handsome young man with a secret identity and plenty of powers to cast away bullies, becoming a beloved citizen of the new land (with admiring females everywhere) in the process. It is not so much that Superman is symbolic, but that the creators’ circumstances gave the work its power. Jerry Schuster was able to somehow channel the powerful forces around them into their characters, and into the story of those characters’ struggles.

A similar “channeling” of social forces took place with Melville. Jeffrey Hole dives into the life and times of Herman Melville and surfaces with a fascinating set of ideas. His premise is that Melville was writing in part to understand what was America was becoming at that moment in history: a nation with global reach. Herman Melville was trying “to provide a literary understanding of the intensification and transnational reach of American power during the nineteenth century.” Melville’s fictional explorations are doctrines of empire, the author concludes, or a “theorization of American power.” This, Prof. Hole argues, makes Melville particularly relevant today, as once again the U.S. rethinks and recasts its own geopolitical influence over the globe. In reference to Melville’s work during this period of American expansion, Prof. Hole writes:

I argue that these imaginative works attempt to expose the catastrophic associations between the U.S.’s domestic “problems”—such as Negro slave revolt and Indian insurrection—and the U.S.’s broader global interventions in politics and commerce.

Moby-Dick is a story about movement and energy, about the capturing, violent transformation, and commidification of an animal into a biomass fuel that keeps the world alight. Yet it is also a story about humans confronted with the technologies of capital and industry, with the liberalization and expansion of commerce, and the conquest of the Pacific. The ancient practice of the hunt gives way to an absolutely modern arrangement of power that privileges movement and speed, the management of laboring bodies, the charting of space, and the enforcement of property. “Possession is the whole of the law,” writes Melville rather sardonically.

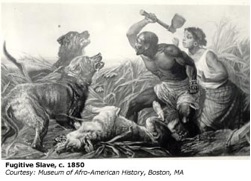

Here is the event that did more than anything else, the authorargues, to lend shape to Melville’s story of a great hunt: The Fugitive Slave Act. This was an extremely controversial law declaring that that all runaway slaves were to be captured and returned to their masters. Abolitionists nicknamed it “the Bloodhound Act,” for the dogs that white slave owners could now legally use to retrieve runaway slaves. Law officials were obliged to aid in the capture. Anyone caught helping slaves run away could be imprisoned for six months and fined $1,000. Prof. Hole’s thesis is that, after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, Moby-Dick could no longer be merely a romantic adventure of whaling; the furor over the new law obliged Melville to come to a new and deeper “understanding of ‘the chase’ and obliged the writing of a different kind of book, one ‘wicked’ and ‘banned’”:

President Fillmore, on September 18, 1850, signed legislation that would expand “federal power [for] the interstate rendition of fugitive slaves.” In April 1851, several months before Melville published Moby-Dick, Judge Lemual Shaw, then Melville’s father-in-law, abandoned his “opposition to slavery on grounds of natural right” and enforced this law by deciding that the fugitive Thomas Sims should be returned to bondage.

In light of these events in the early 1850s, critic Michael Rogin has argued that Moby-Dick signals Melville’s rebellion against the “liberal fathers” who, like Lemuel Shaw, had forsaken their commitment to “human freedom” in order to maintain “social order.”

For a general reader like me, it takes some time to fully grasp what Prof. Hole is saying – but it is more than worth the effort, since these same ideas can carry over to other works of fiction (John Steinbeck, for one). Two immediate examples are Mark Twin’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, two works deeply influenced by the same act of Congress. For another example, The Transformers and The Terminator series can be seen, at heart, as paranoid colonization stories where American society is conquered by our machines (or alien machines); they are mirror images in many ways of Melville, revisionist tales where Americans are on the receiving end of the projection of power.

The lessons in “Melville Infidel” travel well. If this topic is of interest to you, I hope you will take the time to look at his dissertation. Understanding a single author in great depth pays unexpected dividends.