The Gothic, Postcolonialism and Otherness

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON A POWERFUL IDEA

The Gothic, Postcolonialism and Otherness

GHOSTS FROM ELSEWHERE

Tabish Khair

Interview by Punyashree Panda

The Gothic mansion, home to an enduring fiction genre. From 1979’s “Fall of the House of Usher.”

Introduction

Of the many concepts I throw at my tired students in my ongoing attempt to jolt them into critical thinking and writing, “the Other” is always popular. Students see the value of the Other right away because we all spend so much time reading, watching, and telling stories – and we all know that certain characters are dealt a bad hand. These characters are portrayed as one-dimensional. They do not get

backgrounds, flashbacks, or human motivations, or sympathetic characteristics of any kind. We never root for them. In monster movies it is the monster, in cowboy movies it is the Apache, in film noir it is often the pretty femme fatale.

Gothic literature rose in the 18th century. Patrick Kennedy of Farleigh Dickinson defines it as “writing that employs dark and picturesque scenery, startling and melodramatic narrative devices, and an atmosphere of exoticism, mystery, fear and dread. Often, a Gothic novel will revolve around a large, ancient house that conceals a terrible secret.” Writers as diverse as Charlotte Bronte, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Edgar Allan Poe fall under the Gothic umbrella.

In this ambitious work, scholar Tabish Khair places the Other in a colonial and postcolonial context. The seminal Gothic stories were written during a jarring age of colonialism, when European nations were conquering and culturally subjugating native cultures around the world. Shock waves of this global disruption left their mark on this distinctive literature. Tabish Khair suggests that when Mary Shelley writes about the Frankenstein monster, or when Robert Louis Stevenson describes the devilish Mr. Hyde, it is also a colonial Other that they are describing, a racial Other. Such stories, he argues, gain power and resonance from the parallel story beneath their surfaces, the story of empire, its many costs and many implications. Seen in this light, Frankenstein and Dracula can be understood as European stories about Europe’s fear of invasion by the conquered tribes of Ceylon, or Africa, or Calcutta.

As I tell my students, you don’t have to agree with a theory like this in order to enjoy reading “Frankenstein” or “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” – but it is

worth weighing when trying to explain why these stories endure. We all need to look under the hood, to see what assumptions drive these popular stories.

This feature is very much a cousin or companion to two other features in this journal. In “Masked Fictions: English Women Writers and the Narrative of Empire,” Prof. Nalini Iyer shows that domestic household works can also be imperial narratives. While classic imperial adventures like Robinson Crusoe, Lord of the Flies and The Heart of Darkness tell the male side of empire – the exploration and conquest and administration of the colonies — such works as Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights can tell the female side. Similarly, our feature on “Dracula as a Foretelling of World War I” showcases Genesea Carter argument that Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel “Dracula” can be read as a premonition of World War One. Carter sees the novel’s depiction of a siege of vampirism descending on England as a foreshadowing of the destruction that would soon befall England when her young men encountered the terrible death dealt by modern warfare. The very scenario which frightened readers of Bram Stoker’s novel – that a monstrous foreign entity (from the Austro-Hungarian Empire) invades innocent England using unforeseen, forbidden tactics to slaughter her citizens – came horrifyingly true less than two decades later.

Here, Tabish Khair applies that same colonial lens to the Other.

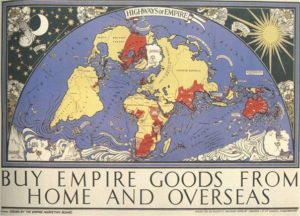

Depictions which underlie Gothic literature coincide with the rise of European empires.

Empire Marketing Board poster ‘Highways of Empire’ by Macdonald Gill.

Review of “The Gothic, Postcolonialism and Otherness”

Tabish Khair Reviewed by Tom Durwood

In this rich and robust work, a most resourceful scholar locks horns with a powerful idea – the Other – and offers new perspectives on Gothic literature. The writing is lucid and the progression of ideas from Mary Shelley through two centuries of literature to modern-day terrorist portrayals is clear and well-presented.

An important pillar of Tabish Khari’s construct in “The Gothic, Postcolonialism and Otherness” is that globalization is the engine which drives Gothic stories. That is, our encounter with “foreign” cultures and places and religions – that is what really scares us, since it poses a threat, or an alternative, to who we are. A true horror story threatens our idea of ourselves. A Gothic story is about identity, the fear of losing ourselves. Heathcliff, the brooding, highly disruptive hero of Charlotte Bronte’s “Wuthering Heights,” is like a colonial terrorist, a dark presence from elsewhere who is attacking the heart of society, the quaint English village. That is why it is so shocking when Catherine declares “I am Heathcliff.” Yow!! How is that?? She is accepting the Other in the most total way. That is love.

Another link between the Other and globalism that Khair offers is that Mary Shelley’s original “Frankenstein” was written during a period of violent slave revolts in the Caribbean. Therefore, since current events tend to leach into the imagination of our writers, it is safe to say that the compelling qualities of this scary-yet-in-the-end-sympathetic monster, Frankenstein, are some of the same qualities of slaves becoming accepted citizens and neighbors. As different as they may seem, all they want is acceptance.

The author’s structure for this book is sturdy. He begins with an Introduction to the Gothic and Otherness, then proceeds to a consideration of Western images of devils, and how closely those can resemble racial Others. European writers often used distorted -Caribbean elements in their descriptions of Satan. His third section, Postcolonialism and Otherness, traces specific readings in specific authors (Erna Brodber’s “Myal,” Herbert G. De Lisser’s “The White Witch of Rosehall”) in which the ‘conquered’ cultures write back, and create their own fictional worlds, with very

different heroes and very different monsters. He concludes in a final section which points to new uses of the Other in the age of tribalism.

Khair takes us on a walk through the Gothic literary forest, pointing out its quirks and attributes as we stroll. He proves to be an excellent guide. Here he points out a favorite story:

Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau is a good example of the Gothic-influenced story or novel that takes place in the ‘colonies’ and reflects the doubts and ambivalences nurtured in the heart of Englishness/civilization by exposure to … the ‘Otherness’ of colonial power.

Quite a sentence!! While I have enjoyed The Island of Dr. Moreau without attaching any

theory to it, I look at it in a new light when it is connected to this broader trend of empire. You can also see here how Tabish Khair ventures off into new texts but continually returns to his themes (something I continually remind myself to do with my own writing), so his readers are never lost in the expanse of his exposition. Another example:

Count Dracula is a member of a separate aristocratic ‘race’ set on consuming innocent victims and … establishing an empire within the British empire.

So there is a caste system among demons! Colonial horror stories reflect the fears of their times, and the infiltration of the upper class is one such fear.

As gleefully as Imperial stories cast demons in the aspect of the colonized,

Postcolonial stories seek to correct the record — to reconstruct identities using

Gothic characters and settings. For students, and non-expert teachers like me, one

work that seems pivotal in all of the postcolonial portrayals is Wide Sargasso Sea. Author Jean Rhys places her direct focus on the “madwoman in the attic” character that appears in Charlotte Bronte’s “Jane Eyre” and flips the script. Rhys gives this character the fuller, more sympathetic treatment that she deserves. We learn about her childhood in Jamaica and her unhappy marriage to a cruel Englishman. In this work, a one-dimensional madwoman is turned from an “Other” to a fully realized and sympathetic heroine, with complexity and flaws and humanity.

The Gothic haunted mansion is still very much with us. The old-turned-new idea

driving Suspiria, The Amityville Horror, The Conjuring and all other versions of that same

story spring from the Gothic house setting – a cursed home, where an innocent

family is threatened by a mysterious evil power of unknown origin (usually buried in

the past). The family is the U.S. population, the house is America, and the threat is

Arabia, or Mongolia, or Java, or any heathen colonial culture. From the ensuing clash

which takes place in a voodoo dimension, the family’s identity emerges, intact

(Paranormal Activity) or destroyed (The Shining). The sin that generates the haunting is

often a colonial one (the housing development in Poltergeist desecrates a Native

American burial ground, for example). Monster theory.

In a contemporary example of Khair’s colonial Other premise, one of today’s most powerful and highly charged narratives warns of “Otherized” immigrants storming the borders of civilization. Refugees at the frontiers of Texas and Hungary are often depicted as faceless hordes of criminals. This is a by-now familiar political tactic of dehumanizing people we cannot deal with easily. Our narratives pave the way for our actions.

In the marketplace of literature, some works flourish while comparable works disappear. Why is a 200-year old novel like “Wuthering Heights” still inspiring movie versions, operas, and hundreds of thousands of new readers? What is its secret power? That is a question the author helps us answer by connecting the story to its powerfully resonant imperial foundation.

The points I mention here are extracted from a large tableau set forth in this ambitious work. Tabish Khair is learned and ambitious, and his expansive writing covers a great deal of territory. He is really setting out to give a history of both the Gothic and the Other. General readers like me are well rewarded for a close reading of this challenging material.

Still from the 1939 film of “Wuthering Heights,”

with the brooding disruptor Heathcliff (Laurence

Oliver)

Interview with Tabish Khair

Tabish Khair and Empire Studies in the Classroom

October, 2018

- You have written that “the object of our fear tells more about the epoch we live in than the substance of the fear itself.” What do current popular narratives

tell us about ourselves?

Tabish Khair (TK): Byung-Chul Han talks of how we have moved to a ‘neurological age’: an age characterised by the excess of positivity. He contrasts it to the ‘immunological age’ of the 19th-20th century, where the landmark diseases of the popular imagination – usually bacteria and virus-borne – were characterised by the negativity of what is immunologically foreign. Now, he notes, the landmark diseases of the 21st century are depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline personality disorder (BPD), burn-out syndrome – all characterised by an excess of positivity. These are infarctions, not infections, Han notes.

Hence, to take just one example, our narratives of illnesses reflect the functioning of society and capital, which is now centred on an excess of positivity. The current neo-liberal myths are that one just needs to work, plan and be wired to technology in order to be successful, or that if you fail, you have only yourself to blame, not some exploitative employer. Of course, no one would say that the old narratives disappear: how can they when old lifestyles do not disappear? There are still people digging out minerals by hand, even as the world is dominated by people who move financial figures around on a computer screen and get rich without doing any physical work. This is just one example of how the objects of our fear tell us a lot about ourselves, how we live in reality.

Still from Bollywood’s “Stree.” Ghosts carry different meanings in different cultures, and are not always unwelcome.

2. Why should students care what lies beneath the surface of our narratives? Do these same ideas apply to the narratives students tell?

TK: Reading is essential to thinking; thinking is essential to reading. And the point of reading is not just to recognise the landmarks of an alphabet, but also take into account the gaps in between. If we do not pay attention to what lies under the surface of narratives, then we basically fail to read and understand: we just repeat the obvious; we buy into someone else’s reading at the best. Fundamentalists, religious or political, always want you to read in only one way! They want you to read mechanically, as if you were telling beads or reciting the multiplication tables.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

The Gothic, as a narrative of terror, depends on a perception not just of ambivalence but also of opposition and ‘irreconcilable’ difference.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

- Ghosts seem to mean different things in different societies. You refer to

“colonial ghosts” and unresolved guilt from the Raj. Chinese ghost culture has more to do with the wisdom of dead relatives (“The Guards of Impermanence”).

Do ghost stories cross cultures?’

TK: Actually, in a recent paper on ghosts in Indian literature, I point out that often, in India, ghosts can be seen as falling in love with the living and vice-versa. Ghosts are not just objects of fear, perhaps because death is not final and eternal in Indian religions. The dead and the living can co-exist without any ‘norm’ being broken. So, yes, you are right: different cultures relate a bit differently to ghosts. But ghost stories qua ghost stories can still cross cultures today, perhaps because all of us do share certain elements of ‘modernity,’ which makes a very sharp division between past and present, death and life.

- Is the “other half” being told today? How have portrayals of Indian society changed since August, 1947?

TK: Not as drastically as the leftists think, if you belong to the minorities. There was always an assumption that ‘India’ equalled upper-caste Hindu values. Now it is just being said more clearly in many quarters. This can be good or bad, depending on how ordinary Indians react to it, and how they treat other ordinary Indians. India will be forced to face itself, finally. And actually the ‘other half’ can never be fully told; it can only be an endeavour, not an achievement.

- What trends do you see in the classroom that you feel are counter-productive? TK: Too much easy and distracting technology. Technology should be an aid to thinking and human endeavour, not a shortcut around them. There is no shortcut to thinking or knowledge: it always requires work. Technology that is essential in an advanced laboratory is not necessarily what should be used in a classroom.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

The ‘other half’ can never be fully told; it can only be an endeavour, not an achievement.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

- You link certain portrayals of evil with “otherness.” Why does one villain resonate with a reader, while another falls flat?

TK: My position on otherness differs a bit from the common postcolonial position. Postcolonialists see the other as just a negative construction, which of course was the way it mostly was and is in colonial discourses. But the philosophical notion of the other is different: the other is that which is central to the self and finally beyond the self. Hence, the colonial depiction of the other as a negativity or lack is as simplistic as some multicultural postcolonial attempts to represent the other as basically transparent and the same as the self. Both kheer and firni as rice pudding, to put it simply. As for villains, well, villains – like heroes – are reflections of ourselves. Taking simple examples, even as a child reading comic books, I never liked Superman, as he was too sure, invulnerable and perfect, but I liked Batman and Spiderman, because they were funny at times and always a bit vulnerable and conflicted. I think often the heroes we like are the ones we can relate to, and the villains we really fear are those who reveal suppressed and dangerous or unwanted sides of our own personality.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Under advanced capitalism, one does not need to rule territories but to control their markets, and have the power to disrupt them economically.

____________________________________________________________________________________

7. Is India an empire? Is China an empire? Is USA an empire? Are similar dynamics at work in these ‘national’ fictions?

No, and yes: India and China are not empires, but they have imperial tendencies. Any large nationalism overlaps with the power structures of imperialism. USA is definitely an imperial power. Under advanced capitalism, one does not need to rule territories but to control their markets and have the power to disrupt them economically: USA has had that power, and has used that power, throughout the second half of the 20th century, and even more recently. Some kind of relative monopoly in a dominant market – the arms industry, for instance – is also sought and often achieved: on-going, endless limited-scale conflicts in the world are a reflection of this.

_______________________________________________________________________________

In India, ghosts can be seen as falling in love with the living and vice-versa. Ghosts are not just objects of fear …

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Moreover, now with neo-liberalism taking over from classical capitalism, basically what an imperial power does is try to be attractive to ‘free-floating’ capital, and provide its share markets with an edge by any means possible. That is what the USA has been doing in the last few decades, but, here, China, for one, is trying to make in-roads now. As for fiction, evidently the easy ability of USA to ‘export’ its fictions is an aspect of its imperial status.

The “madwoman in the attic” is an enduring Other portrayal, seen early in “Jane Eyre” and recently in “Wide Sargasso Sea.”

# # #

The interview and response are comprehensive and beyond easy digest. Fluid lubricant would have helped better. Nonetheless brilliant exchange of knowledge, idea and emotion. Cheers.

A handwritten book is a book