Geometry, Radar and Empire

by Judd Ammon Case

Copyright @ 2010 Judd Case

A History of Grids

Related Topics: Critical Thinking

Communications, Technology

Social Studies

This is an excerpt from the complete dissertation, which is available here:

This new C-band, 3 megawatt radar with a 50-foot dish antenna has recently been installed on north Kennedy Space Center. It is one of the largest of its kind in the world, providing higher definition imagery than has ever been available before. (Photograph Wikimedia Commons)

Introduction

My students always get a kick out of writing like this – provocative, smart, funny, and taking with a big idea. In this case, the idea is really big: that radar was a precursor to GPS in giving us a way to conceive of our universe, and to map ourselves within that universe (and that is only part of the thesis). Here are two typical sentences:

In the 19th century, Geronimo could cut a telegraph line and affect an empire’s grid. He could disrupt communication between forts, throw off the train schedule, stop the settlers from ordering seed, and make it difficult for the cavalry to arrive.

To me, this is writing so vivid and original that it stays the reader’s mind a long time. When we read texts like this out loud in class, the ideas are so challenging and out-of-the-ordinary that, at first, the cadets are startled. Then we stop reading and one of the students makes a connection — then a light bulb seems to go on over the entire classroom.

In his dissertation, Professor Judd Case looks at the history of grids from the Nile, which pulled all of us into a grid of its cycles and rhythms, for our own protection; to geometry; to the British military’s invention of radar in World War II to keep the Luftwaffe at bay; to Sputnick; to television and finally to the contemporary grids of the IPod, internet, and blogoshpere. This interview and excerpt is only a fraction of the whole, a sort of sampler of the many narratives in the full dissertation. I think it is a wonderful introduction to Walter Benjamin, semiotics, and big thinking in general.

Here, Judd Case offers writing that is so rich with ideas that I can only read two or three pages before I have to stop and process it. This is not easy going, but it is certainly rewarding. I hope that after you read the interview with Professor Case and the excerpt, you will read the entire dissertation.

Interview with Judd Case |

07/2011 |

1. Mathematics seems to figure into every empire, whether in navigation or engineering or technologies of warfare. How did geometry impact 20th century empires? Did it affect them differently?

Before the 20th century, empires’ lines and points were difficult to secure. People could see, hear, or touch telegraph lines, sentry towers, search lights, messengers, port authority offices, and so on. They could map empires’ flows, track their rhythms, and challenge their orderings and arrangements. In the 19th century, Geronimo could cut a telegraph line and affect an empire’s grid. He could disrupt communication between forts, throw off the train schedule, stop the settlers from ordering seed, and make it difficult for the cavalry to arrive. In the 18th century, Parisians could see the food wagons rolling through the countryside. They could gather in cafés or impasses, or on avenues. They could sense the distance and isolation of Versailles. Before the 20th century, people could exploit empires’ vulnerable lines and points.

In the 20th century, though, empires added lines and points that were mediated, private, and controlled. Searchlights could be seen by most anyone within range, but radar pulses could only be seen by those with the knowledge and means to detect them. Civil War Generals surveyed fields with spyglasses, but by World War I Generals were in distant rooms watching films recorded by surveillance aircraft. Sentries on towers can be hit with rocks, but taking out spy satellites requires the means of a nation state or a Bond villain. The short of it is that during the 20th century empires added remote lines and points. Digital technologies further extended this remoteness as geometries became even faster, more secure, and integrated.

Today, grids are so controlled and extensive that Osama Bin Laden was located, in part, by his absence from them. He wasn’t in the phone cells, or showing up on Facebook, let alone on the identification software at the airport. When the Navy Seals took him out, they placed him on a grid, on a video sent all the way back to the White House. Today, empires are in the business of remote control, and those who challenge them have to adapt.

2. One of your more provocative statements is that radar “…contained the potential for catastrophe.” Why is that? What catastrophes could the invention and use of radar cause?

“But even as it was intended to expand and secure the nation state, to coordinate first military and later civilian movements, and to function as an electronic rampart, it contained the potential for catastrophe.”

I think progress and catastrophe have a Jekyll-Hyde relationship. I sometimes consider them in physical terms: progress as forward movement and catastrophe as collision. I’m especially interested in collisions as there’s reality in every wreck, an unrealized progress narrative in every ruin. 9/11 was a moment I realized that, on the flipside, airplanes were missiles with passengers. During Katrina, I considered that interstate highways were one hurricane away from becoming parking lots, refugee camps, or graveyards. Last year, when oil was gushing into the Gulf of Mexico, I heard reports of how quickly it approached the coastal marshes and how slowly officials reacted. I wondered at our inability to contain our own collision.

Radar can extend nation states. When I say this, I’m thinking of things such as the Battle of Britain, the U.S. Air Force tracking Sputnik, and Israel using radar to detect tunnels between Egypt and Gaza, as well as the more pedestrian coordination of commercial flights. This extension obliterates distance between nation states and time for deliberation. Radar multiplies opportunities to perceive threats and can magnify the effects of those perceptions. When radar is mislead by countermeasures or operators’ misinterpretations, the movements of troops, supplies, and civilians can be manipulated. When radar is mislead by nature—such as by Libyan Desert Glass, migrating swans over the Suez Canal, or the moon over Thule, Greenland—its potential for catastrophe is also evident.

Radar also contributes to the remote, prediction-based, push-button grids that enable nation states to exercise the kind of authoritarian control that concerns Lewis Mumford. On a day-to-day basis, radar’s contribution is to things like coordinating commercial air traffic, patrolling national borders, and issuing speeding tickets, and it is not catastrophic. But when its technical attributes are exploited—such as when United Flight 93 disappeared from radar screens because the radar systems lost it in the concrete jungle—it contributes to catastrophes. When the 9/11 Commission Report discusses the hijackers’ attempts to disappear, it does so in terms of radar.

3. For the general reader:

a) What is semiotics?

Semiotics is a branch of linguistics that is also taken up in communications, anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies. It is interested in how words, symbols, and other objects structure meaning through contrasts, through distinctions between one word and another, one concept and another, one object and another. The upshot of semiotics is that language creates meaning through difference and that one can understand a culture by analyzing its words, symbols, and other meaningful objects.

b) Who was Walter Benjamin and why is he so important?

Walter Benjamin was a German-Jewish intellectual who committed suicide on the French-Spanish border while trying to escape the Nazis. He corresponded with thinkers such as Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Georg Lukács. His work blends historical materialism, German idealism, and Jewish mysticism, and ranges from interpretations of Baudelaire to musings on technology, history, urban space, aesthetics, fascism, and the human condition. Those in empire studies could probably sink their teeth into his The Paris of the Second Empire.

Benjamin is important to discussions of technology and culture, to aesthetics, to assessments of Baudelaire, and to historians. I am taken with his historical method, and particularly with his assertion that ruins and other objects that are not absorbed into progress narratives have disruptive power. He approaches historical objects as a quasi-surrealist or art critic; he arranges them into constellations and tries to disrupt the mythology of progress.

4. What ideas did Harold Innis set forth in Empire and Communications that you feel have such meaning for us today?

Empire and Communications considers how communication impacts empires’ centralization and decentralization, economics, and political change. This approach minimizes the distance between ancient and modern civilizations and erects a media-driven superstructure over time and space. It’s sweeping, high-handed, and historically dubious, but it’s also conceptually rich. For while Innis died long before the rise of the blogospere, his work anticipates how so many websites could proffer the same talking points and how satellite TV could deliver hundreds of channels carrying the same stories. Conceptually, Innis’ Empire and Communications is way ahead of his time.

Innis is also relevant to contemporary discussions of logistics. In some ways, Innis helps me articulate my notion of logistical media. Scrolls, tablets, monuments, books, newspapers, soldiers, priests, and emperors sweep through his narrative and convey a sense of movement, order, and arrangement. Innis never quite articulates a notion of logistical media, but nevertheless, Empire and Communications brims with logistics.

5. All empires depend on effective communication. How did radar help bring about a sort of modern global empire, where the global spaces were traversed by new “technics?” Here is the James Carey quote you use to introduce this idea:

…With the development of the railroad, steam power, the telegraph and cable, a coherent empire emerged based on a coherent system of communication.

Radar provides a point of view, a collection point for information, and in this sense it can centralize decision making. Radar helps transform pilots into passengers, into technical operators who follow the pathways established by beacons and the directions provided by air traffic controllers. At the same time, radar puts aircraft, automobiles, ships, orbiting satellites, hurricanes, tsunamis, asteroids, and so on under surveillance. In the aggregate, the effect of radar as a collection point is the ordering of objects into traffic, into a flow that enables a kind of imperial forecasting. In this aspect, radar bestows on its controllers decision making power that results from information moving more quickly than the objects providing it.

When radar is networked and operated with imperial authority, it has the power of a live, 24-hour media operation. In the situation room in Cheyenne Mountain, the officers in charge behave as producers and directors, the operators as script writers, the transmitters and receivers as cameras, the screens as frames of film, and the fighters, bombers, satellites, missiles, and other objects as actors. This is how radar writes an empires’ narrative, how it draws its lines and gathers power to its points. Carey’s discussion of telegraphs in the American West starts my thinking in this direction, but with authoritative, networked radar the blanket of electromagnetic waves, stations, remoteness from the masses, portability, and immense power to coordinate objects brings objects into an empire’s narrative anywhere on the globe (or beneath the globe, or in space) it is deployed.

7. You make a connection between electromagnetic waves and mythic ideas about invisible energy. What were those mythic ideas?

When I connect electromagnetic waves to mythic ideas such as the All-Seeing eye and the bible teaching that “God divided the light from the darkness,” I’m claiming a relationship between information and movement (or in-formation, such as ships in a convoy or trumpeters in a marching band). I’m not especially interested in a relationship between energy and movement. For me, information is the fundamental object that is ordered and arranged in the name of logistics. Religious, governmental, economic, and military authorities mediate this ordering and arranging, and in this way they shape progress narratives. In this way their work is mythic and meaningful.

8. How would you explain this quotation from Harold Innis:

Because of modern forms of communication, “the balance between time and space has been seriously disturbed with disastrous consequences to Western civilization.”

Innis says that an overabundance of light, easily moved, and short-lived communication leads to colossal, center-heavy, and unstable empires. In his analysis, such empires are dominated by a few points of view that are quickly and broadly circulated. If you imagine Roman couriers with papyri bearing the emperor’s dictates, Canadian trees being chopped down for the New York newspapers, and cell phone news bytes being dominated by the national parties’ talking points, you understand Innis’ concern for balance. Moreover, since Innis was Canadian and wrote about the American newspaper industry, it’s hard not to suspect that he was concerned about being on the periphery of the huge newspaper chains in the U.S.

Innis acknowledged that Western civilization had counterbalancing, time-biased communication, but they didn’t seem sufficient in the face of the glut of immediate, ephemeral, broadly experienced media. He thought that without counterbalance, Western Civilization would be besieged by problems of time, such as the gradual accumulation of pollution, depletion of resources, and degradation of infrastructure. He thought that Western civilization would try to stabilize itself through the use of force.

9. In the following passage, you are wary of “authoritarian technics:”

Paul Virilio (1989) wrote of the logistics of perception that the movie camera brought to World War I, of the ways generals thereafter observed battlefields remotely. Lewis Mumford (1964) described how authoritarian technics—things like air traffic control systems, interstate highways, and camera networks—endanger nation states even as they are supposed to keep them in synch.

If that is so, then you must be terrified today, with handheld devices like iPhones and iPods covering the planet. How have today’s technics advanced your theory about radar? How have these devices changed our own sense of time and place?

Nation states deploy authoritarian technics, and citizens can sometimes sense that these technics can themselves undercut nation states. When citizens build bomb shelters, they might sense the potential catastrophe lurking behind their military initiatives. When they bristle against security scanners at airports, they sense the threat to their freedoms. When cell phone data is used in court cases to prove when they were at specific locations, they might wonder if the right to remain silent is being trumped by networks that record passively provided feedback. Authoritarian technics help nations states remotely coordinate and control their populations, and there is always the possibility that they will become alien hands.

Because radar is my prop to advance a theory of logistical media, much of what I say about radar translates into discussions of recently developed technics. Actually, I arrive at radar history by working backward through things like iPods and RFIDs, and even through new applications of radar such as anti-collision and ground penetrating systems. I consider how cell towers, surveillance cameras, electromagnetic waves, and other traffic control mechanisms occupy cities long after the people have gone back to the suburbs. Today’s technics have me wondering about how cell towers and Wi-Fi affect traffic flow, how a street in Chicago would become a ghost town without coverage. They have me considering the pervasiveness of mutual monitoring, video phone journalism, online police work, and the war on terror. Today’s technics advance what I’m saying about radar in that the issues of remote control, movement, and collision take new forms in the tangle that is modern telecommunications.

Today’s technics change our sense of time and place by creating, in the language of logistics, new movements, collisions, and points of view. Crowds of people wearing their iPods or talking to “no one” through their Bluetooths, clusters of texters, stray Wi-Fi wanderers, the woman running her business from the coffee shop, and the odd photo phone creeper presume social forbearance in most places and most of the time. Where the mediated variety of homo communicus is prevalent, space—whether physical or virtual—is flooded with collisions, “WTF?” moments, technics, lines of information, points of view, and demands for flexibility. Today’s technics have made us a society of contortionists; we crave the freedom of the nomad and the fantasy of the virtual, don’t always think of surveillance as audience, and wonder if the tweets we send and the photo cops we speed through will cost us.

10. You write this about the scientific management of society:

Kevin Robins and Frank Webster (1999) argued that the scientific management of society has overlapping economic and military implications.

Do the cell phones we carry around today have military implications? What are those?

In a word, “yes.” Any technic that provides information about identity, location, and intention, that passively transmits information to databases, and that can be monitored remotely has military implications. Specifically, cell phones have military implications when they are used to monitor borders and terrorists, or when they are taken off the grid to help stop protests or revolutions. Certainly, militaries could learn plenty from monitoring the cell phones of an occupied citizenry and even of their own soldiers. I also presume militaries have their own apps that provide new forms of remote control on battlefields and in occupied cities.

11. How do you connect the lighthouse, Nicola Tesla’s mythic “death ray,” and the events of 9/11?

Logistics.

12. What is your idea of a “state of emergency?” How is it different from Naomi Klein’s? Is that what we are living under today?

I refer to a “so-called state of emergency” as Benjamin’s present. It is a state of prediction, forecasting, prognostication, spectacle, and habituated behaviors that help nation states maintain their progress narratives. In the present, supposed imminent demise is a spectacle, ratings device, and reason to go to the mall, and there are few genuine emergencies. In the present genuine emergencies are avoided, downplayed, commodified, and even suppressed. The summary description I use in my dissertation is, “the present uses the threat of emergency in an attempt to sustain a state of non-emergency.”

I do think most of us live in the present.

I also think Klein and I agree on emergencies’ importance and qualities. However, where she emphasizes economic crises and how corporations sweep in with a new, capitalistic narrative ready for consumption, I emphasize how nation states’ prevent genuine crises from emerging in the first place. Additionally, I’m more concerned with technological and logistical aspects of emergencies than is Klein, and, like Benjamin, I assert that the disruption of the present can lead to healthy social change. So, if I understand Klein, she and I are working different aspects of similar—or identical—phenomena.

Excerpt from the Dissertation “Geometry, Radar and Empire”

by Judd Ammon Case

Copyright @ 2010 Judd Case

The King’s Postal Service

Radar is not only scientific, is not only waves, transmissions, and Doppler effects. My reading of Innis (1972) suggests that radar is also rooted in religious, governmental, and military logistics. Innis describes the priests of Osiris and Ra, the kings and royalty, and “military nobility” in logistical terms (p. 41). Throughout his discussion of Egypt, these three—religion, government, and the military—undulated with power derived from the Nile. As Innis relates:

The Nile, with its irregularities of overflow, demanded a coordination of effort. The river created the black land which could only be exploited with a universally accepted discipline and a common goodwill of the inhabitants. The Nile acted as a principle of order and centralization, necessitated collective work, created solidarity, imposed organizations on the people, and cemented them in a society. In turn, the Nile was the work of the Sun, the supreme author of the universe. Ra—the Sun—the demiurge was the founder of all order human and divine, the creator of gods themselves. Its power was reflected in an absolute monarch to whom everything was subordinated. It has been suggested that such power followed the growth of astronomical knowledge by which the floods of the Nile could be predicted….

Hearkening to the Nile’s movements, religion, government, and the military cultivated an Egyptian mythos as surely as peasants cultivated its flood plain. Innis wrote that, “The demands of the Nile required unified control and ability to predict the time at which it overflowed its banks,” and religion, government, and the military inscribed themselves in those demands (p. 44). Soldiers oversaw the ordering of resources and arranging of people in the construction of pyramids that projected the power of the Nile’s kings and priests over

time and space. Astronomer priests created a calendar that “became a source of royal authority” through synchronizing religious festivals and the Nile’s movements (p. 32). With the advent of papyrus, kings’ holy messengers were transformed into a divine, private postal service.

As taken as I am with Innis’ narrative, I am not suggesting that radar is the progeny of the Egyptians’ divine postal service. Radar transmissions are not embodied messengers and do not possess a holy mandate. Radar stations measure movement and order, but are not equivalent to shrines to Thoth (an Egyptian god to whom Innis attributes rules of conduct). Moreover, modern nation states do not usually blend religious, governmental, and military authority as frequently or directly as did ancient Egypt.

Today, the Potomac River initiates orderings of time and space that aren’t altogether different from Innis’ Nile logistics: port procedures, fishing seasons, contracts for water use, watercraft speed limits, farm runoff regulations, minimum bridge heights, riverboat casino licensing, and dumping statutes shape the movements of people near the Potomac. Still, no one thinks officers of the Coast Guard, Fish and Wildlife Service, or EPA bear missives from the mighty god of the mid-Atlantic. Nonetheless, the mythos of the pharaohs’ divine postal service continues to shine, Ra-like, through the founders of all order in our day. In that sense, it informs an understanding of radar. Conflicts such as those between Israel and Palestine and between Tibet and China mingle religious, governmental, and military logistics. Addresses in Salt Lake City pinpoint the distance to the Mormon temple and its battlements. 9/11 hijackers pointed at Mecca before they pointed at the World Trade Center, Pentagon, and Pennsylvania field.

______________________________________________________________

The speed of the Ark was the speed of the entire nation. It was a divine pace car, a police cruiser that no one dared pass.

______________________________________________________________

Even today, the religious, governmental, and military cultivation of mythos occasionally resembles Innis’ (1972) descriptions of ancient Egypt and Babylon. In his biography of Innis, Alexander John Watson writes that consistencies between ancient civilizations and the contemporary U.S. were exactly what Innis had in mind when he wrote Empire and Communications. According to Watson, Empire and Communications was “the foundation on which [Innis] built his understanding of the contemporary world, in particular his view of the United States of America, its foreign policy, and its effects on other cultures” (Watson, 2007, p. 18). Innis, a Canadian, paralleled the ways papyrus changed the politics of ancient Egypt with the ways the newspaper changed the politics of the United States, Canada, and Europe. He traced the relationship between the natural—the Nile and Canadian trees—and the mythical and logistical—the kings’ holy papyrus carriers and American paper boys.

In this study, historical objects from MIT’s Radiation Laboratory Historian’s Office lead to an Innis-like mixture of the ancient and the contemporary, of religious, governmental, and military logistics. Some of the objects that anticipate radar—such as lighthouses—have significant religious logistics. Others, like Nikola Tesla’s death ray, are wrapped in a mythos of military power and quasi-religious utopianism. 9/11 has elements of all three, and helps me draw conclusions about both radar and logistics in a general way. With these in hand, I now integrate my preceding discussions of the Big Bang and Innis into a discussion of the intersection of science, religion and radar logistics.

Let There Be Light and Logistics

Electromagnetic waves recur in some mythic explanations of the origin of the universe, and can help us think about how deeply aspects of logistics and radar are rooted in the Western mythos. Genesis 1:3 says that “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light,” and then posits a foundational digitalization, “and God divided the light from the darkness.” The Qur’an has a passage that reads like a description of the Oscillatory Universe, a scientific model that argues that the universe perpetually alternates between expansions and contractions. The New Testament has a passage that could be consistent with the Big Crunch, with the universe ending in a multi-billion year collapse into itself.

______________________________________________________________

The Nile, with its irregularities of overflow, demanded a coordination of effort … The Nile acted as a principle of order and centralization

______________________________________________________________

Perhaps most importantly, the Old Testament notion of the firmament puts the earth at the center of the universe and divides the observable from the unobservable:

And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters. And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven.

(Genesis 1:6-8)

For the ancient Hebrews, the firmament, or heaven, was a boundary beyond which they could not see. It was a perimeter, an absolute and fixed range (not an ever expanding universe), and it was established with them at the symbolic and logistical center.

Radar and the All-Seeing Eye

There is something of both firmament logic, of the sky as something that can be mapped, and modern science in many radar systems, something that technologically puts the radar operator at the center of an apparently set and circumscribed universe. The radar reader is a surveyor, a would-be All-Seeing Eye or Eye of Providence who perceives, differentiates, and orders objects in relation to himself. Airplanes, satellites, and storm clouds emerge and swirl just as the stars, moon, and sun did on the ceiling-sky of the ancient Hebrews, and the radar operator’s position seems objective and superior, even as it perceives only the surfaces of select objects. Twenty four hours a day, during smog and fallout, through season finales, reruns, and writers’ strikes, radar systems can fill space with live transmissions and provide their readers with mathematically-precise information, with coverage. Like the astronomers and priests of ancient Egypt (Innis, 1951) they mimic aspects of the cosmos and make traffic of the masses.

Old Testament Tabernacle

Like pyramids, obelisks, totems, shopping malls, and cathedrals, the Old Testament Tabernacle was a logistical medium, a device of orientation, an artifact for urban planning, symbolically a microcosm of the universe as the ancient Hebrews understood it. It had an inner, most-holy area that was partitioned from the holy area, which itself was bounded as though within a firmament (Smith, 1900). Only particular

bodies and objects were allowed in particular spaces, and then, only at prescribed times, after required procedures, and for the duration of strictly controlled activities. Once a year, on Yom Kippur, the High Priest entered the Holy of Holies in memoriam of Moses’ experience at the burning bush, of his witnessing the thermal and electromagnetic mode of God. The Tabernacle always faced east, which was believed to be the direction from which God, like the rising sun, came. The Levites, who cared for the Tabernacle medium and controlled the communications, camped immediately around it on three sides (not on the east side) and the tribes of Israel were assigned to camping spots on the north, south, east, and west.

The dead and the unclean had to remain outside the perimeter of the camp. No one of another nationality was to camp freely with the Israelites; the Israelites’ presence made it holy land, made it national space. The ancient Hebrews traveled in camp formation (except on Shabbat), with the Ark of the Covenant preceding them.

The Speed of the Ark

The speed of the Ark was the speed of the entire nation. It was a divine pace car, a police cruiser that no one dared pass. When the Israelites stopped, the Ark rested in the Holy of Holies, in the center of their civilization. But when they marched it was put to use building highways, clearing the land, and wiping out enemies.

The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) records that:

The Ark was not merely a receptacle for the Law; it was a protection against the enemies of the Israelites, and cleared the roads in the wilderness for them. Two sparks, tradition relates, came out from between the two cherubim, which killed all serpents and scorpions, and burned the thorns…. (Jewish Encyclopedia, 1906)

We should then, think of the ancient Hebrews as nomads. Like retirees driving RVs, they took their civilization with them wherever they went. Logistical media such as the Ark can enable the compression and portability of culture.

______________________________________________________________

We should then, think of the ancient Hebrews as nomads. Like retirees driving RVs, they took their civilization with them wherever they went. Logistical media such as the Ark can enable the compression and portability of culture.

______________________________________________________________

The Kaaba

Muslims also have an object at the logistical center of their religion, the Kaaba (“sacred house”) in Mecca. Five times a day, Muslims face the Kaaba and pray in its direction. Their messages are sent during different increments of the day, such as between dawn and sunrise. As part of transmission, Muslims resituate their transmitter bodies and assume new subject positions in relation to the Kaaba. They stand, raise their hands, sit, lie prostrate, and tilt their heads in a precise sequence that makes them aware of their own bodies, and of the bodies of those around them (Cragg, 1970). All of this coordinated, harmonious movement and message sending is a performance of both Muslim unity and narrowcasting (because it involves a homogenous audience). Muslims also perform unity during the pilgrimage to Mecca, through what they call the tawaf, a counter-clockwise circling and touching of the Kaaba during the Hajj. During tawaf, a pilgrim’s speed and trajectory must yield to other participants if collisions and trampling are to be avoided. The centralized management of moving bodies is the primordial task of logistical media such as radar and the Kaaba.

Praying in the right direction is so important that mosques have alcoves in the wall to tell Muslims which way to face and lay their mats. Muslims also have qibla compasses, compasses that have 40 zones marked around the edge so users can know where they are in relation to Mecca and decide the correct direction for prayer. The most advanced digital qibla compasses are Mecca-centric GPS systems that require no knowledge of either angles or distances. They simply tell users which way to pray by presenting an arrow on a digital display. Where stationary radar systems give information about their proximity to selected objects, and usually moving objects, qibla compasses tell moving Muslims where they can find the stationary Mecca. An airline pilot using a radar system to locate the airport and a Muslim traveler using his qibla compass to find Mecca coordinate their movements in logistically similar ways.

The Telegraph

Of course, other, and even earlier, media have also extended the logic of the nation state. Carey (1988) observed that the telegraph coordinated the expansion of the U.S. across North America in the mid and late 19th century, that it “provided the decisive and cumulative break of the identity of communication and transportation.” He further observed that:

The great theoretical significance of the technology lay not merely in the separation but also in the use of the telegraph as both a model of and a mechanism for control of the physical movement of things, specifically on the railroad. That is the fundamental discovery: not only can information move independently of and faster than physical entities, but it also can be a simulation of and control mechanism for what has been left behind.

(p. 215)

The common quality of logistical media is their grid-like functioning, which may or may not be evident in how they represent information. Carey (1988) wrote that “the grid is the geometry of empire,” (p. 225) and we could certainly think of radar, the telegraph, cell phone towers, traffic lights, parking lots, the Tabernacle, the radio dial, and congressional redistricting in these terms. As Innis does, we could think of the number and density of powerful, ideological, and technological grids that coordinate and control movement in any given space as a measure of its imperial occupation. A continuum of least to most occupied spaces might be: uncharted wilderness, shepherd’s field, federal wilderness area, national forest, rural farmhouse, neighborhood home, suburban tract home, apartment building, gated community, World Trade Center, Disney World, airport, Mecca during the Hajj, the West Bank, military base, missile silo, the Korean demilitarized zone, the Pentagon, mausoleum vault.

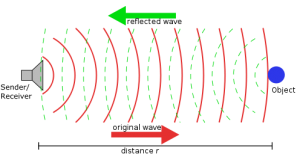

Sender and Receiver

How does radar fit into the ‘geometry of empire?’ Radar is a series of technologies that represents objects and facilitates their coordination. Its main functions are detection, identification, and coordination, and it accomplishes these by bouncing electromagnetic waves off objects and receiving their echo signals (which, because they have been reflected,

are of a slightly lower frequency). These electromagnetic waves are nothing more than light waves of a particular length and frequency. In the broad spectrum of things, gamma rays, x-rays, and ultra violet rays all have a higher frequency and are shorter than visible light. Infra red waves, microwaves, radio waves (including UHF, FM, and VHF), and long waves all have a lower frequency and are longer than it. Typical 1930s and 40s radar operated in the 100-200 MHz range of the spectrum, the range that would soon be used for commercial FM radio and network television. Today radar systems operate on frequencies as low as a few MHz and as high as 248 GHz (Skolnik, 2001).

But how, you might be wondering, do radar transmitters work? How does light come off of an antenna? An example is in order. As mentioned above, electromagnetic waves are different from sound waves (which are mechanical and are not made of light and are much, much slower), and the two should never be confused. But, if you think of a radar transmitter as the electromagnetic equivalent of a tuning fork, you’re on the right track. If you strike a tuning fork, you can see it vibrating and can hear sound waves radiating from it. If you have several tuning forks, each of a different mass, and you strike them all at once, you can hear different notes. These notes are different because their frequencies are different—the tuning forks vibrating more quickly are producing higher notes. If we think of a radar transmitter as a tuning fork, what strikes it is an alternating current (AC) of electricity. Electromagnetic radiation will emanate from radar transmitters at the same frequency as the AC current they conduct. The same goes for television transmitters, the FM station across town, and the microwave oven in your kitchen.

Speed and Weapons

“Sufficient speed makes anything a weapon: Speed is violence. The most obvious example is my fist. I have never weighed my fist, but it’s about 400 grams. I can make this fist into the slightest caress. But if I project it at great speed, I can give you a bloody nose…As Napoleon said, “Force is what separates mass from power” (Virilio, 1997, p. 37). For Virilio, speed is the unexamined element in political, physical, and military power. It permeates industry, class distinctions, and biology. It is also a meta-medium of perception, what Virilio calls the dromoscope (2005). In a manner reminiscent of Schivelbusch’s (1986) description of panorama and the mediating train car window, Virilio discusses the seventh art (that of the dashboard) and applies it to the appearance of modern reality itself: As driver-directors we sit before our windshield-easels and adjust our scene-speeds with our motor-projectors. We are both actors in and producers of our own perceptions.

Understanding New Technologies

New technologies are often understood in terms of technologies that have already been situated by political, economic, and social forces. Whether early cinema is understood as moving photograph, cars are understood as horseless carriages, or DVD players are understood as digital VCRs, the tendency to structure and envision technologies as logical extensions of their predecessors is strong.

— End of excerpt —

This is an excerpt from the complete dissertation, which is available here.

Judd Ammon Case is currently Department Chair of Communication Studies at Manchester University. Dr. Case (Ph.D., University of Iowa, 2010) specializes in media studies and teaches courses in media literacy, new media, telecommunications, guerrilla journalism, and TV criticism. He is a member of the review board of the Journal of Media & Religion.

POSTSECONDARY LEVEL

L E S S O N P L A N T O A C C O M P A N Y

“Geometry, Radar and Empire”

JOURNAL OF EMPIRE STUDIES FALL 2011

1. How does the author compare geometry and radar? Why are they significant?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

2. What is an “All-Seeing Eye,” a concept which seems to occur in many different cultures? Do we have one or more of these today?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

3. What did Napoleon mean when he said this: “Force is what separates mass from power?”

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

4. Drone missiles can see everything you do from two miles in the sky. They are like “all-seeing eyes” with death rays. Are drone missiles a fair way to fight a war?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

5. Is there a down side to the grid represented by Facebook? Do you like being traceable, or would you prefer to be “invisible” to the grid to which the author refers?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

6. Why does the author say that the Nile river was an original universal “organizer” or grid? Why did people care about the Nile?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

7. What is a qibla? What sort of grid does it represent?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

8. Will you have a new and more powerful type of grid to track your children in twenty years? What might it be?

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________

Today, teenagers can simply go on their phones and get directions to wherever they are trying to go. What they do not realize is how this is made possible. The answer lies in radar. Radar allows us to gather knowledge that we did previously have that help can help us with making future military decisions, whether that be gathering military intelligence or simply figuring how to get to a store across town. I do have a little bit of previous knowledge regarding radar because my father makes parts for military radars and then sells those radars to the military across the country and even companies like Boeing. I even have had the opportunity of working hands-on on these parts and began to gain an understanding of the phrase “military-like precision”. Radar is something that has been used across the world as an incredible tool and resource. Of course, with this type of military technology today, there is bound to be miscommunication that could possibly lead to conflict between countries. What I am curious about is what comes after radar and how will this new idea have an impact on the world?