Empire Films and the Crisis of Colonialism, 1946–1959

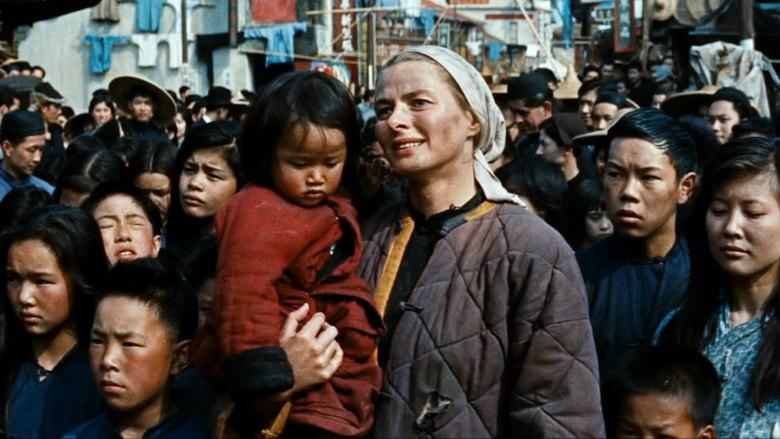

“Inn of the Sixth Happiness,” one of the revealing mid-century “empire” films studied by Jon Cowans

by Jon Cowans

Introduction

Ours is a highly narrativized culture: from childhood, you and I have watched (and heard, and read) more stories than we can count. From this slush pile of consumed narratives, we all have a history of empire in our memory banks. We have seen many imperial plots, images, scenarios and attitudes played out in various short and long dramas, and in various disguises, some crude and some subtle. We know the mechanics and shifting values of rising empires, high empires, and falling empires.

One important lesson from Jon Cowans’ excellent book is that all those stories – from cartoons to The Revenant, from Bonanza to Halo, from The Princess Diaries to car commercials – reveal something meaningful about our society and the ways we think. Cowans asserts that movies capture their times, if we can only read the signs closely. In his study of a specific grouping of wide-screen narratives, Professor Cowans argues that through the movies we watch, scholars can gather more information than opinion polls can deliver, and information of a different kind. In their imageries, in the interactions among the races and classes, in their large story arcs and their smallest details, popular movies are an invaluable reflection of their times.

While this book is valuable to specialized scholars as a study of a particularly eventful era, Professor Cowans’ book is also valuable as a general introduction to the larger field of film and empire. His close reading of movies demonstrates the idea that almost all stories can be mined for political content. Few stories during this period escape the underlying reality that the 20th century was a product of empire, and the era’s events, institutions and attitudes were largely a function of dramatic changes in empire.

Editorial Note:

Professor Cowans’ work is directly related to three other features in this journal. You will quickly see how these three titles connect:

— “Masked Fictions: English Women Writers and the Narrative of Empire”

— “Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City”

— “John Ford’s Heirs: A Theory of Film and Empire.”

Deborah Kerr wearing prizes of empire in the 1947 movie “Black Narcissus”

Jon Cowans Interview

June 2016

What were the global dynamics of empire that gave rise to the rich group of mid-century films you cover?

There were plans to grant independence to a few colonies before World War II, but the war really accelerated the process for reasons the book’s introduction explains. Basically, it changed material conditions – Britain, for example, faced new financial limits on its ability to wage wars while meeting domestic demands for better living standards – and it promoted ideas such as freedom and self- determination and discredited notions of racial superiority among colonizers and colonized.

Decolonization intersected with the Cold War in complex ways. Washington, for example, feared that if its European allies’ colonial subjects were denied independence, they would ally with Moscow or China (after 1949). Yet it also believed that the Europeans needed their colonies for economic recovery, and it feared alienating its European Cold War allies by supporting colonial liberation movements. The Europeans themselves were generally less conflicted, as all but a few left-wingers remained committed to keeping their empires. How strongly they felt about that is a matter of ongoing historical debate, and one my book addresses directly.

There were many films on imperial topics because with the rise of competition from television in the 1950s, film industries were looking for good material for wide-screen epics and adventure films – things television could not do. There was also more location shooting then, and the search for exotic locations resulted in many stories set in colonies.

In addition, given filmmakers’ interest in topical material, the growing visibility of racial issues resulted in a lot of films on colonial topics. Setting tales overseas allowed filmmakers to comment indirectly on the touchy subject of American race relations, as in Something of Value (1957) and Island in the Sun (1957).

Finally, the 1950s were the heyday of the classic western, a subgenre of empire films, and an avalanche of westerns dealt with American Indians and their relationships with Euro-Americans. These historical settings allowed filmmakers to insert racially liberal messages at a time when direct comment might have run afoul of Southern audiences and studio executives wary of HUAC’s anti-communism.

You mention Edward Said and Frantz Fanon, among other writers. What works would you recommend to college students or general readers who are interested in this topic?

Said and Fanon are essential reading, even if their ideology now looks pretty dated to some of us. They are, in my view, more valuable as primary sources revealing the anti-colonial ideologies of the 1960s and 1970s than as scholarly works on the history of colonialism.

As for more recent works, at the risk of omitting many worthy works and scholars, I would recommend, on the culture of empire, Richard Slotkin’s Gunfighter Nation and Christina Klein’s Cold War Orientalism; Ella Shohat and Robert Stam’s Unthinking Eurocentrism is also vital on the cinema of empire.

On empire itself, I like Ed Berenson’s Heroes of Empire, Dane Kennedy’s The Last Blank Spaces (and other works of his), and anything by D. K. Fieldhouse, Bernard Porter, Ann Stoler, William Roger Louis, Fred Cooper, Andrew Thompson, and Benjamin Stora.

Can you explain why you feel Broken Arrow (1950) is such a pivotal movie? How can you compare it to more recent films like “Dances With Wolves” or even “Avatar”?

Broken Arrow has long been credited, quite wrongly, as the first “pro-Indian” film. Films had been criticizing whites’ mistreatment of American Indians for years; The Vanishing American (1925) is but one example from the silent era, and John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) was another from more recent times. What Broken Arrow did was to present a critique of white mistreatment of Indians in such a way that people found it powerful without being overwhelmed by it. It was well-made, with some good performances and location photography, and an easy story to follow, and although it used white actors to play Indians (as did nearly all films then), it developed compelling, likable Apache characters and showed viewers dimensions of Indian cultures rarely shown before. Devil’s Doorway, released in the same year, is also pretty compelling, but its indictment of white behavior toward Indians went beyond what the studio believed people could accept, and it got poor distribution. The contrast between the two films’ fate is instructive about the difficulties of finding just the right level of political critique for a given historical moment.

Dances with Wolves is another example of finding just that right level for its time, though by then people could handle an even stronger indictment of white behavior. Scholars have been pretty hard on both films for their sentimentality, for not going even further politically, and for the sorts of inaccuracies seen in all historical films, but their success with audiences and critics proves that the filmmakers knew what they were doing. There are limits to how didactic or depressing you can make a film and still keep an audience. If no one goes to see a film, what good does it do?

Your study starts in 1946. Can we see “ambivalence in public opinion about colonialism” in earlier films like “Gunga Din” and “Gone With the Wind”?

I don’t see much ambivalence about colonialism in those films. GWTW doesn’t even acknowledge that it is a colonial system.

There has been Western opposition to colonialism as long as there has been Western colonialism, and there have been films critical of colonialism since the early silent era (though most others were pretty racist and colonialist through the 1930s). I started my study in 1946 because I wanted to see what films and their reception could tell us about Western thinking about colonialism in the era of decolonization.

You look in depth at 1955’s “Simba” as an example of a powerful film that got both “the Other” (in this case, the Mau Mau rebels) and the white settler protagonists wrong. Is there a movie which a general reader might know that stands in contrast to “Simba”?

Something of Value (1957) was fairer toward the Mau Mau revolt. It made clear that black Kenyans had very legitimate grievances, even if it ultimately condemned Mau Mau’s methods and mainly called for whites to treat blacks better (rather than to grant independence).

Something of Value (1957) was fairer toward the Mau Mau revolt. It made clear that black Kenyans had very legitimate grievances, even if it ultimately condemned Mau Mau’s methods and mainly called for whites to treat blacks better (rather than to grant independence).

How would you explain the “white woman’s burden”? Does the concept hold today — is it different in today’s films?

I found that between 1946 and 1959 many films showed white women acting heroically in colonial settings – braving hardships to bring civilization to needy peoples, often as teachers or missionaries. These included Anna and the King of Siam (1946), Black Narcissus (1947), The King and I (1956), The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1958), and The Nun’s Story (1959). Focusing on women worked well for what I call liberal-colonialist films, which still favored white rule but opposed more violent and exploitative forms of colonialism. The idea that white people should “take up the white man’s burden,” as Kipling’s 1899 poem urged Americans to do in the Philippines, could apply to women as well, and if the goal was to promote a more altruistic and benevolent form of colonialism – or at least to fend off decolonization by making colonialism seem more gentle and nurturing – then telling tales about women made sense. We often call colonialism paternalistic, but it could also be maternalistic, to coin a term.

Those films mostly disappeared after The Sins of Rachel Cade in 1961. This was in part because films about missionaries went out of style in the more secular and cynical 1960s. The Julie Andrews character in Hawaii (1966) comes off well, though her fanatical husband does not. There was also Anna and the King, the 1999 remake of the Anna Leonowens story with Jodie Foster, but the whole notion of white people heroically civilizing the darker races mostly disappeared from cinema in the 1960s.

Did the influx of European directors (and writers, and movie craftsman) like Billy Wilder and Eric von Stroheim influence Hollywood’s depiction of empire?

I find it especially hard to keep movies in national categories by this time. There were countless Europeans working in Hollywood, Americans making movies in Europe (mostly refugees from HUAC’s anti-communist witch hunts and the Hollywood blacklist), and Hollywood “runaway” productions, films shot in Europe with European crews to save money and to deal with European protectionist legislation blocking the repatriation of earnings. American and European filmmakers also influenced each other. I don’t see Europeans in Hollywood bringing a distinctive view of empire with them. One of the reasons why I took a transnational approach, looking at the United States, Britain, and France, was this difficulty of classifying films nationally, as well as the considerable overlap among attitudes toward colonialism in the three countries. I do discuss some national differences, including in the reviews, but I contend that very similar patterns and forces existed simultaneously in various Western countries.

How did French imperial movies differ from British, and from American movies, during the period you consider? Is there an underlying difference in the colonial “vision” or attitude of these three cultures? Does the same difference apply today?

The French made very few films about empire in these years, largely because of political

censorship. I discuss one film, Le Rendez-vous des quais (1955), about opposition to the Indochina war (at a time when the Algerian war was underway). The French police seized the film after one day, and it was years before anyone else saw it. The book does discuss two largely overlooked 1957 French films about the Indochina war that got wide distribution and fairly positive reviews, so claims that the French did not make films about colonialism at all in the 1950s and did not want to revisit their recent colonial defeats are not true.

Britain also had political censorship but produced a few more films on colonial topics. Many of these come off as propaganda depicting empire as altruistic and protective of helpless peoples.

In terms of reception, there were more left-wing newspapers and magazines in France, and those were often more critical of empire than papers in Britain and the United States. There were also a couple of far-right publications in France that were more enthusiastic about colonialism than any American or British paper was. The French admired Americans’ freedom to film colonial topics and their willingness to air their dirty laundry. All three countries published a wide range of views on colonialism, including a lot of mixed feelings. It was a transitional period, leading gradually toward anti-colonialism becoming the dominant public view.

“Broken Arrow,” a movie which the author says reflects a reconsideration of colonial values.

You cite this mid-century period as one in which colonialism and its consequences is being reconsidered by movie audiences. How would you characterize the period 1960-1973, the subject of your next book, in those terms?

The next book (in progress) continues the story, which was too big for one book. A lot of people have written about individual films or films on one region, but I thought it was important to consider how those pieces fit together and what films set in different places had in common. The next book will argue that after a few more years of 1950s-style liberal-colonialist films, there was a fairly sharp anti-colonialist turn in Western cinema around 1966, followed by several years of strongly anti-colonialist movies that did well with audiences and critics.

An essential problem I see was that Western filmmakers had to learn how to make anti-colonialist films. The impulses to question colonialism are visible in the films made from 1946 through the early 1960s, but the genre was rooted in tales of Western heroism and it was hard to rework it for new times.

Filmmakers tend to copy previous films, and significant changes in films about colonialism and race only really emerged with the advent of a new generation of young filmmakers and very different political outlooks around 1966.

You write that “messages are embedded in virtually all films.” Do the movies we see today — like “Transformers” or “The Revenant” — carry messages about colonialism? Are the dynamics of empire different today?

One can indeed find messages and positions on colonial issues in many current films. Statements about colonialism were pretty incidental in The Revenant, but one could still identify a fairly coherent outlook about Native Americans and their early encounters with whites. The film’s outlook is mostly sympathetic to native peoples, even if it told the story from a white man’s point of view.

One can indeed find messages and positions on colonial issues in many current films. Statements about colonialism were pretty incidental in The Revenant, but one could still identify a fairly coherent outlook about Native Americans and their early encounters with whites. The film’s outlook is mostly sympathetic to native peoples, even if it told the story from a white man’s point of view.

Colonialism has become pretty thoroughly discredited since the late 1960s, so impulses to intervene in Third-World affairs now face greater skepticism, and no governments want to admit that their actions qualify as colonialist or imperialist (terms once used proudly). Interventions in the Third World certainly still happen, but the imperative to make them appear altruistic and beneficial are somewhat greater than before. In terms of recent films specifically about empire, one sees a diverse range of political perspectives, including some fairly old-fashioned flag-waving as well as some pretty critical outlooks. Films remain crucial in getting people to think about these topics, and both the films and the reviews of them tell us much about public attitudes on matters of empire.

Book Review

Empire Films and the Crisis of Colonialism, 1946–1959

The “great man” presentation of history is always entertaining — how Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, Eisenhower and Montgomery won World War II, or Queen Elizabeth’s personal struggle ad triumph in throwing off England’s rivals. These histories are easier for creators to assemble and easier for an audience to digest. Historians like Barbara Tuchman can make events come alive through a dramatic depiction of a handful of leaders – their doubts, their risks, their dramas. More and more, however, I find that these limited-scope narratives are almost absurdly incomplete; they do not include a larger, deeper picture – that of the nation beneath the leader. The sweeping social and economic forces at work beneath the top-view histories lend resonance to these rich, complex stories. I love watching the movie Selma, for example, but it only makes sense when paired with the documentary Eyes on the Prize.

In his excellent book, Empire Films and the Crisis of Colonialism, 1946-1959, Jon Cowans takes on a most substantial challenge: what did Western civilization think about empire during the 20th century? How did our often-conflicting attitudes develop and change? The author looks closely at popular mid-century movies from the United States, Britain, and France to see what citizens thought and felt about winning, enjoying, and losing their empires. He looks at over 100 films from the postwar era and finds common threads that trace changes in our attitudes about colonialism.

His premise is simple: a close look at the films we watched can tell you almost everything you need to know about popular opinion of the day. Today we have metadata to help us read the tea leaves – for those pre-Google years, we have movies. “Filmmakers returned repeatedly – almost obsessively – to colonial topics,” writes Cowans, “and the appearance of new films every year on these subjects allows for fine-grained historical analysis.”

And Cowans’ analysis can certainly be fine-grained. Here he dissects the amount of screen time given to colonized natives and their livestock in this period and genre of cinema: “Animals often get more screen time, particularly in films set in Africa. Native life was cheap in empire films, which often featured the slaughter of faceless warriors who fought stupidly.” Hence, I would add, the colonizers’ “magic” bullets, which fell dozens of enemies while the white hero is unscathed. In this passage, Cowans agrees with Jane Tompkins, who in her landmark book West of Everything notes that actual Native American characters get almost no screen time in Westerns.

Once we accept Cowans’ premise, we see that powerful cultural undercurrents are at work in these films (as they are in today’s films). We may watch George Stevens’ 1956 film Giant the first time for the romance between upper-class Bick (played by Rock Hudson) and Leslie (Elizabeth Taylor) — and the working-class member of the triangle Jett (James Dean) — but we view it a second and third time because of the deeper themes beneath the soap opera: the emergence of the American woman; the rise of Latino culture; and the giddy arrival of the fossil fuel economy.

It seems clear that, at some point in the twentieth century, something

fundamental changed in Western thinking about colonialism.

The book’s first part, “The Persistence of Empire,” looks at pro-colonial depictions of white imperialism in Africa, Asia, and the American West. Professor Cowans looks at the positive portrayal of both genders of “white protectors” on a mission to uplift and “civilize” natives. The second section, “Coming to Terms: Confronting Insurgency and Decolonization,” concerns the end of the process of empire, and how both sides of the relationship begin to cope with the changed status. This is especially timely in light of India and Pakistan, both of which nations became independent in 1947.

The book’s third section, entitled “Dangerous Liaisons: Interracial Couples in Films,” studies a particularly powerful flashpoint in the changing cultural landscape of colonizer and colonized. “If these films indeed led viewers to think more about people of color,” the author concludes, “and to reconsider their assumptions of racial difference, then cinema played a significant role in undermining one pillar of colonialism.”

One clear theme that Cowans uncovers is our gradual disenchantment with colonialism. While movies like King Solomon’s Mines and The King and I celebrate empire, other films like Island in the Sun and John Ford’s Broken Arrow narrate against the social injustice and cultural superiority which empire brings. In their imagery, in their characterizations, and in the trajectories of their plots, Cowans finds valuable clues indicating an audience that is having second thoughts about the riches of colonialism. He goes beyond literary analysis by looking at the business of movies as well, including trade figures and newspaper reviews.

A cinema subset he considers at length is the group of films that depict “forbidden love,” racially charged romantic relationships between white colonizers and nonwhite colonial subjects – if this sounds familiar, it is because contemporary dramas like Avatar and A Passage to India do this as well. A second category deals with films depicting the excesses of empire, a broad group that could include not only exotic foreign settings but also most of the romantic comedies set in Manhattan, where the material splendor and the prizes of empire displayed and consumed can seem gleeful.

Edward Said, the godfather of empire studies, says that all stories are political, whether they intend to be or not. Certainly Said would agree with Professor Cowans that these popular movies captured our ambivalence about imperialism and paved the way for decolonization. In the middle of the 20th Century, both England and France dismantled their global empires, just as empires rose in the East. The two world wars catalyzed the process. Politicians reflect the will of the people – and, looking back, you can see the will of the people in their films.

A critic calls this book “the first truly transnational history of cinema’s role in decolonization.” I would add that it is also an introduction to a most revealing field of study. This is a history of all of us, as challenging as it is rewarding.

Professor Cowans is currently working on a new book which puts films from 1960 through 1973 under the microscope.

# # #