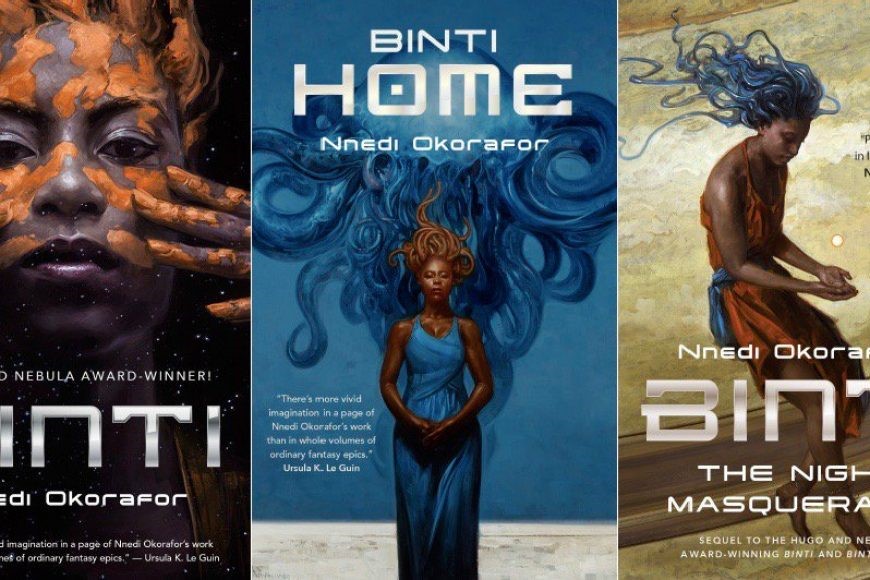

Empire and Higher Education in Nnedi Okorafor’s “Binti”

Breaking Colonial Conventions, Confronting Past and Future

by Amanda Lagji

Editor’s Introduction

“The Empire Writes Back” is a powerful concept. It is a phrase coined by Salman Rushdie in a magazine article and then expanded in a book of essays (edited by Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin). It refers to a vibrant and vast body of literature told from the viewpoint of ‘the colonized.’ If the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries saw the rise of European colonial empires, then the 20th saw the beginning of a “postcolonial” period, The rainbow-rich cultures of giant nations (India) as well as tiny island cultures (Trinidad) began to take back their language, and to tell narratives from their own viewpoints – not that of the colonizer’s.

This is one context to keep in mind in considering the “Binti” books by Nnedi Okorafor. They represent a new wave of authors who works written in part as a reply to J.R.R. Tolkien – these are epic fantasies written from diverse new perspectives, in this case an African perspective. In its way, “Binti” — as well as books like Tomi Adeyemi’s “Children of Blood and Bone,” and earlier works “Shadowshaper” and “An Ember in the Ashes.” — is part of the “Empire Writes Back” movement. The ‘conquered’ cultures are now creating their own fictional worlds on a par with the worlds of European and American writers.

In this well-considered essay and interview, scholar Amanda Lagji explores one specific aspect of the Binti story, one that appears in other epic fantasies – schools and museum, and how they can act as agents of empire. Robert Heinlein features a boot camp for imperial space-warriors, Harry Potter has Hogworts, “Star Trek” has Starfleet Academy, and so on.

The Premise of “Binti” In the Binti narrative, a young woman is accepted into a prestigious intergalactic university, Oomza Uni. She is forced to run away from home to take this opportunity, and soon she finds that powerful forces oppose her. This begins Binti’s quest, not only to find her own place in the universe, but also to reconcile new knowledge with the ancient traditions of her people.

If most of that sounds familiar, it is because almost any epic fantasy comes with certain conventions which readers expect – journey to discovery, wise old mentors (who often die in the second act), sidekicks, magical creatures and fantastic artifacts, trips into the underground, foreshadowing and flashbacks, etc. These are all elements established by “The Lord of the Rings” saga, written by a scholar who mined mythology for many of these elements. What is new is the texture of the setting, the imagery, and the special kind of story points brought by a West African language. Here, the rules set up by the mostly Caucasian European (English, that is) epic fantasists are changed by an infusion of African motifs and themes.

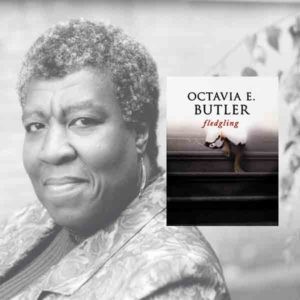

Afrofuturism Authors like Samuel Delaney and Octavia Butler initiated a tradition of speculative fiction rooted in African culture., often called “Afrofuturism.” In his essay, “Afrofuturism, Science Fiction, and the Reinvention of African American Culture,” scholar Myungsung Kim holds that this new wave of authors “appropriate devices from science fiction and fantasy in order to revise, interrogate, and re-examine historical events insufficiently treated by literary realism.” This merger of technology and black culture has created disruptive approaches to fiction, recasting our collective stories with a very different emphasis. Certainly HBO’s “Watchmen” fits this bill, using a science fiction premise to re-examine narratives from America’s Civil Rights era.

Kimberly Wickham, in her excellent paper “Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy,” reminds us that fantasy authors have long used the fantastical to express dissenting opinions.” She continues:

Works of Epic Fantasy often have the reputation of being formulaic, conservative works that simply replicate the same tired story lines and characters over and over. That many works of Epic Fantasy choose to replicate the patriarchal structures found in our world is disappointing, but it is not an inherent feature of the genre. Other possibilities exist.

These epic-fantasy conventions seem innocent enough, yet at a certain point they are corrosive, for what they omit; the lack of characters of color sends a powerful message. Writes Ebony Elizabeth Thomas in “The Dark Fantastic:”

The implicit message that readers, hearers, and viewers of color receive as they read these texts is that we are the villains. We are the horde. We are the enemies.

There are ideas beneath all stories. A reader’s job is to delve below the characters, dig up those ideas, and give them a good look.

Two novels which serve as pillars of conventional young-adult world-building fantasy.

Interview with Scholar Amanda Lagji

August 2019

1. What three ideas would you like readers to take away from your essay?

First, I hope readers begin to take the lens I use to analyze Binti and think about the spaces and institutions they inhabit, and consider how colonial or settler pasts are not distant, but are folded into the present. Second, I would challenge readers to think about the role of higher education and disciplines in privileging or discrediting ways of knowing; how do various disciplines define or value knowledge? And third, I would love for readers to seek out other Africanfuturist, Afro-futurist—or more generally, contemporary African—fiction.

2. Behind the interstellar travel and alien warfare, “Binti” and “Binti: Home” and “Binti: The Night Masquerade” are identifiable as coming-of-age stories. To what degree does the Binti saga build on coming-of-age stories before it, and to what degree is it completely new?

As a coming-of-age novella, Binti reminds me a lot of Nervous Conditions, by Tsitsi Dangarembga. The ending of Binti is a bit more hopeful for Binti’s future at Oozma, but both texts share a concern about the ways that education—and especially, colonialist educations—require a debasement of self and disavowal of culture. Both authors, strikingly I think, write strong, young, female protagonists who are intrepid and reflective. And both Binti and Tambu (the protagonist in Nervous Conditions) feature in trilogies! Together, these fictional texts ask what the cost is of coming-of-age in the worlds they inhabit: what losses might they accrue to attain success or ‘development’ in the social contexts they find themselves? Rather than reconciling oneself with the world, these protagonists challenge their worlds to change to accommodate them. And I think that’s a significant difference.

3. How do schools need to reckon with the legacies of empire? How might Nnedi Okorafor answer that question?

It is impossible to disentangle the legacies of empire from white supremacy; in the United States, we see a robust debate about reparations, about schools whose founders and patrons were slave owners, and about endowments made possible by chattel slavery and the genocide of Native Americans. The land schools occupy depended on the forced removal of Native Americans. Land acknowledgements begin a conversation, but they do not constitute or finish those conversations. The “how” will look different in different places, but it should address everything from the school’s material and physical conditions of possibility (land, capital, labor, etc.) to the production of knowledge itself: Who do we read? Who do we cite? Whose stories and histories am I missing? What counts as knowledge? What are the implicit values of dominant worldviews?

4. Name an author or a work that Nnedi Okorafor’s writing can be compared to (or contrasted with).

There are so many great Black science fiction writers—from Nalo Hopkinson to N.K. Jemisin to Samuel Delaney—but Octavia Butler’s Bloodchild and Other Stories comes to mind to compare to Okorafor’s Binti. Butler’s themes are certainly more ‘adult’ than Okorafor’s young adult fiction; in “Bloodchild,” the eponymous story of the collection, a young human boy comes to terms with becoming a host for an alien species called the Tlic. The stories share an interest in exploring relationships between humans and others that does not reproduce the tropes of human discovery, conquering, and domination. One important difference between the two, however, is the authors’ relationship to Afro-futurism. Whereas Butler is often read as a progenitor of the genre, characterized by “African American culture’s appropriation of technology and SF imagery” (Mark Dery, 1994), Okorafor characterizes her own work as Africanfuturist. This distinction points to the centrality of African continent to her speculative fiction, which we can see in Binti as Okorafor draws inspiration from the Himba people of Namibia. [See also her recent blog post: https://nnedi.blogspot.com/2019/10/africanfuturism-defined.html]

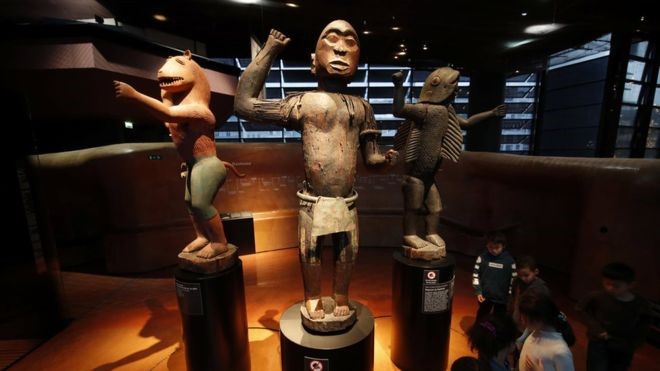

5. French President Macron recently ordered

a report on ‘repatriating’ to Benin artifacts which French museums have been

displaying for decades. They are seen to be stolen objects from colonial times.

Should we be re-thinking the museum displays we see on school trips? Can you cite legitimate museum displays and others which Steven Lubar might find offensive?

This is such a timely question, for many reasons! I’m currently teaching Binti in a course called ‘Decolonial Futures,’ in a unit that explores the decolonial imaginaries of contemporary science fiction. The unit that precedes it, however, is explicitly focused on museums, and we’re reading about the Belgian Museum on Africa, Senegal’s Museum of Black Civilisations, and the histories of Native American Museums and exhibits in the United States. We began the semester by viewing the documentary Etched in Bone, which follows the repatriation of stolen human remains from Gunbalanya, Aboriginal land in Australia. After the documentary, several students remarked that they hadn’t ever thought about how artifacts and objects come to be museums, and that it made them curious and concerned. Museums whose collections consist of stolen artifacts are just some of the more obvious ways museum exhibits can reproduce colonial violence; Amy Lonetree’s Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums describes how exhibits that are not produced in collaboration with tribes or stewarded by tribes tend to rely on an object-based display that situates Native American life and culture in the past. In contrast, she describes a concept-based approach that calls for “[d]isplaying objects in ways that convey both their historic and their contemporary resonances” (22). In short, decolonizing museums will require the repatriation of artifacts, but that’s just the lowest hanging fruit.

6. Is Binti an American story of a Nigerian protagonist, or a Nigerian story, or a story with no nationality? If this had been written by an Indian author, or an Eskimo, would it be different?

I think one of the advantages of speculative fiction is to imagine a world where these questions don’t exactly map on to the way our characters think about themselves and the world. Binti certainly has deep ties to her Himba people, culture, and history, but the novella isn’t interested in whether that corresponds to a nation-state. So, in that sense, it’s easy for me to say that this isn’t a story of a Nigerian protagonist. Is it an American story, or a Nigeria story, or one without a nationality? I think American and Nigerian readers alike can see their worlds refracted in Binti, but I resist the notion that this story could be categorized along national lines. Okorafor herself has spoken at length in interviews about her own identification as “Naijamerican,” a term that allows her to occupy the borders nationality erects between places and people. In that sense, I see her work occupying the same space.

7. For general readers new to literary criticism, what other works would you recommend?

Given the topic of my essay, decolonizing higher education, I would recommend Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Decolonising the Mind, and especially the first chapter, “The Language of African Literature.” Ngũgĩ is a writer of novels, plays, short stories, essay, and literary criticism, and he writes powerfully about the way language mediates one’s relationship to culture, the environment, and history. For those new to African literatures, the first sections of the essay trace some of the debates African writers have been engaged in for decades: What qualifies as African literature? In contrast to the great Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, who famously defended his choice to write in English, Ngũgĩ asks, Why should a novelist “tak[e] from his mother-tongue to enrich other tongues?” (Ngũgĩ 8). I suggest starting with Ngũgĩ because, although not a work of literary criticism per se, I think it’s helpful to read what writers have to say about their own writing.

In terms of literary criticism, I recommend Chinua Achebe’s classic “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness” for several reasons. First, students might have already read Conrad’s novel or be familiar with its plot. Second, it’s an incredibly compelling and persuasive reading of Heart of Darkness; each time I reread the essay, I find it difficult to disagree with Achebe’s reading and interpretation of the text. Achebe addresses characterization, setting, the frame narration, and Conrad’s own contemporary moment—all viable areas of literary criticism. It’s great close-reading and a wonderful model of the work of literary criticism, but more than that, it’s fundamentally changed the way Conrad’s novel is read and taught.

Stung by Empire: Decolonizing Higher Education in Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti

by Amanda Lagji

“You know what they have taken from me,” the chief asked. “Yes,” I said, keeping my head down. “My stinger is my people’s power,” it said. “They took it from us. That’s an act of war.”

Though set in a distant future, one replete with animal spaceships and dangerous alien species like the Meduse, Binti’s exploration of empire, natural resources, technology, and difference speaks equally to European empires and imperial violence—past and present—and an imagined future where colonial legacies are reworked through the fantasy of science fiction.

Winner of the 2015 Nebula Award for best novella, Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti appeals to a young-adult audience through its courageous protagonist, who opts to enroll in the intergalactic Oozma University despite her family’s disapproval. Binti is a master harmonizer, taught how to “communicate with spirit flow and convince them to become one current.” After the Meduse kill all but two on Binti’s ship, and aim to recover their chief’s lost stinger no matter the cost, it is up to Binti to plead the Meduses’ case to the professors of Oozma University. Whereas some of Okorafor’s longer adult novels, such as Who Fears Death, are sprawling longer works, Binti is a pint-sized text easily read for a single class period in the undergraduate classroom. When taught in this context, the speculative fiction of Binti challenges us to consider the ways that higher education institutions and museums must still reckon with the legacies of empire and colonialism before a more harmonious future can be realized.

_______________________________________________

The speculative fiction of “Binti” challenges us to consider the ways that higher education institutions and museums must still reckon with the legacies of empire …

_______________________________________________

Though pitched to a younger audience, the novella engages contemporary and urgent questions about the imbrication of higher education and museum curation in maintaining colonialist collections—vestiges of empire that participate both in the “exotic” rendering of others, and in the exploitation or theft of cultural or personal artifacts. The imperial museum, Steven Lubar observes, “not only served to show off the extent, grandeur, and ambition of the empire by displaying the art and culture of the colonies but also connected the nation to the glories of the ancient world by acquiring Egyptian, Greek, and Roman artifacts.” The museum in question in Binti is one curated at Oomza Uni, and it holds the chief of the Meduse’s stinger. While museums today are governed by no fewer than thirty-seven laws that restrict the acquisition of objects, in the world of Binti the question of legal ownership is irrelevant; the museum, according to the Meduse, has “placed on display like a piece of rare meat…the stinger of our chief.” The Meduse “know of the attack and mutilation of our chief, but we do not know how it got there. We do not care. We will land on Oomza Uni and take it back.”

Although Binti is able to prevent the Meduse’s planned bloodshed at the university and facilitates a peaceful transfer of the stinger back to the Meduse, the right of return is one never questioned by the narrative. Okorafor depicts the professors of the university “shouting with anger” as they discuss “Meduse history and methods” and “the scholars who’d brought the stinger,” but the novella quickly resolves the disagreement with a decision in the Meduse’s favor. Not only will the stinger be returned, but “[t]he scholars who did this will be found, expelled, and exiled.” By situating the museum within an academic institution, Okorafor points to the nexus between knowledge, power, and empire that each institution in its own right exhibits; together, embodied in Oomza Uni’s museum, the imperial logics of looting, theft, and the mutilation of “alien” bodies under the guise of the expansion of knowledge are compounded. Both the museum and the academic institution must confront their complicity in the original outrage, and the return of the stinger as well as the exiling of the academics responsible for the theft are first steps toward what we might view as “decolonizing” the museum and the university.

The stolen stinger, of course, reproduces the patterns of European colonialism in several ways. First, the stinger stands in for the innumerable artifacts taken out of circulation, use, or context and sold, displayed, and gawked at in European institutions. A part of the chief’s body, the stinger also references fragmentation of “other” bodies for the sake of “research” and in service of racial science. Though the chief is technically able to live without the stinger, the episode calls to mind one of the most well-known episodes of colonial exploitation, theft, and dismemberment of an African body, and the calls for return: Sara Baartman. An indigenous African woman, Baartman “was removed by colonial forces and forced to travel in European circles as fodder for European prejudices” in the early nineteenth century, and paraded as entertainment for white audiences. After she died, her body was dissected and dismembered, and various body parts remained on display in Paris until their return to South Africa 2002.

In contrast to this history of racial science, science fiction in the Binti narrative reconstitutes the harmed body not only by returning the stinger, but also by imagining a way to diminish the scars and cultivate wholeness. The Himba people use clay called otjize to coat their skin and hair, and Binti and the Meduse discover that it inexplicably heals wounds. When the stinger is first reattached, Binto notes that “a blue line remained at the point of demarcation where it had reattached—a scar that would always remind it of what human beings of Oomza Uni had done to it for the sake of research and academics.” The narrative seems to shift the onus of remembering from the Meduse to the university academics, however, when Binti applies otijze to the stinger and the scar disappears. Presumably, the Meduse will not quickly forget this history of harm, but the body is not asked to bear these wounds. The decolonial gesture of returning parts of the stolen body extends, then, beyond a simple return of artifacts and to broader, more complicated questions about repairing harm and addressing wounds.

_______________________________________________

The stinger stands in for the innumerable artifacts taken out of circulation, use, or context and sold, displayed, and gawked at in European institutions.

_________________________________________________________________________________

It is no accident that Oomza Uni is implicated so deeply in these histories of harm. In Binti, the weaponization of the university in service of empire is made explicit through the various areas of study at Oomza Uni, and Binti’s position vis-à-vis these imperial inclinations. As an elite institution—what we might consider an intergalactic Ivy League university—Oomza Uni includes “‘a city where all the students and professors do is study, test, create weapons. Weapons for taking every form of life!’” Notably, this discipline is wholly consumed with the study of use and development of weapons—not the history, ethics, or humanitarian concerns of weaponry, but only their potential deployment toward “every form of life.” The human dimensions to this endeavor, where the humanities could usefully intervene, are excised from this academic focus. As a master harmonizer, Binti is situated at the intersection of mathematics and the humanities, able to ‘tree’ mathematics to produce a meditative state, and to harmonize different spirit flows into one. But Binti’s position in Oomza Uni is fraught, and she faces racial and cultural prejudices on Earth, on the space ship, and even on Oomza Uni itself; her own mother foreshadows this tension when she warns Binti that she will become the “university’s slave.” The careful wording here speaks to the way that the university’s values might threaten to subsume Binti’s own, as well as the ways she may be tokenized or exploited as the first Himba to attend. In this way, Okorafor reveals the threat of the imperial university as one not only weaponized against so-called “others,” but also against its pupils.

Just as Binti offers a glimpse of pathways to decolonize the museum through the return of the stinger, the novella also subtly suggests that Binti may prove resilient in the fact of homogenizing ways of knowing privileged by institutions of higher education, where oral histories tend to be devalued in comparison to written records. This tendency, which is prevalent in the narrative world of Binti and in Anglo-American universities more generally, ideologically underpins European imperial expansion and colonialist attitudes. V.S. Naipaul, a sometime apologist for empire and the “supremacy” of European civilization, wrote in the 2010 The Masque of Africa: Glimpses of Africa Belief that “[t]o be without writing, as the Baganda were, was to have no effective way of recording the extraordinary things they achieved. Much of the past…is effectively lost, and can be talked of only as myth. The loss continues. In a literature age, of newspapers and television and radio, the value of oral history steadily shrinks.”

Aware of this racist history, Okorafor takes pains to affirm the oral history and knowledge Binti has acquired in contrast to the potential epistemic violence of the university. Okorafor explains Binti’s incredible and expansive knowledge of astrolabes this way:

…he [my father] saw my face go blank and I started to tree. He would then loudly speak his lessons to me about astrolabes, including how they worked, the art of them, the true negotiation of them, the lineage. While I was in this state, my father passed me three hundred years of oral knowledge about circuits, wire, metals, oils, heat, electricity, math current, sand bar.

Coupled with her mother’s gift of “mathematical sight,” Binti is prepared to “grow that skill at the best university of the galaxy.” Throughout the process of acclimating to the university’s culture on board the spaceship, Binti does not concede the supremacy of the book; instead, she notes “that just because information was in a book didn’t make it true.”

Moreover, the Cartesian divide between mind and body is undone in and on Binti; the history of her family is coded into her hair, which Heru correctly reads as a code of tessellating triangles, but which Binti herself does not explain to him or to the reader. The pattern, Okorafor reveals, “spoke my family’s bloodline, culture, and history. That my father had designed the code and my mother and aunties had shown me how to braid it into my hair.” Thus, knowledge and history are transmitted not only through oral records, but also through material and bodily practices.

Some aspects of the novella are not fully explained—what precisely the edan is that allows Binti to communicate with the Meduse, or why the meditative ‘treeing’ of mathematical equations provides her with clarity to act. Where some readers see development holes, I see Okorafor’s intentional gaps to preserve sacred communal knowledge and practices. These gaps are especially important given Binti’s otherwise excited embrace of Oozma Uni and the promises it offers for her future development. At the end of Binti, not only is the imbrication of the imperial museum and higher education exposed, and decolonial possibilities explored, but the ways of knowing specific to Binti’s people are affirmed and protected.

The novella, though classified as young adult fiction, offers the opportunity to grapple with urgent ethical questions about higher education and museums displaced into outerspace and a faraway future: How might institutions of higher education justify, support, or rely on imperial exploitation in their own pursuit of knowledge? Do museums and collectors ever have a “right” to own or display the cultural property of others? How might we, in the present, repair harms perpetuated and return artifacts acquired by previous generations? In this way, Binti does not simply depict the patterns of empire—it offers a vision of how we might disrupt them.

# # #