Capture the Moment

A CONVERSATION WITH ERIC BERGERUD

THE DYNAMICS OF DEFEAT: The Vietnam War in Hau Nghia Province

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

The Dynamics of Defeat: The Vietnam War in Hau Nghia Province is a book written for military scholars on a very particular subject — yet it is equally valuable to the general reader. In his hunt for particular episodes and specific principles of the Vietnam struggle as it took place in a single province, author Eric Bergerud plows up valuable lesson after lesson on the entire Vietnam experience that can serve as guideposts for us today.

His premise: the part reflects the whole. “Although the major decisions of the war were made in Saigon or Washington, an examination of the microcosm of struggle at the province level makes possible a clear and basic understanding … of the nuts and bolts of revolutionary warfare.” The complex dynamics he captures in this most pivotal region reflect the overall pattern. He depicts military strategies in the proper or larger context of politics and sociology – for example, when American agricultural advisors succeeded in boosting rice production, only to see violent battles destroy the Hau Nghia farmers’ rice fields.

What follows below is a combination of interview and correspondence.

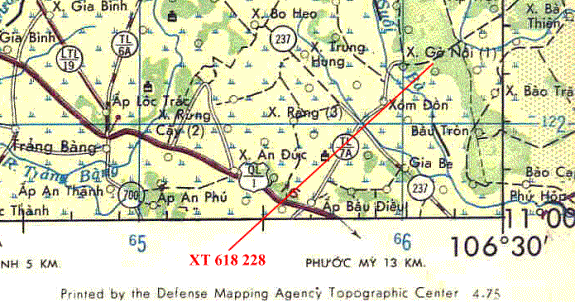

Detail of topographic map of Hau Nghia Province

Credit: Togetherweserved.com

THE DYNAMICS OF DEFEAT

The Vietnam War in Hau Nghia Province

By Jason S. Ridler, Ph.D.

Interview Conducted 28 February 2013

WHY THIS ARGUMENT?

The argument made in the book was one that came out after of the end of the war. As a graduate student at Berkeley, Bergerud met ROTC head Carl Bernard who had been deeply involved the “village war” in Vietnam and encountered a view of the war that was complex and unfamiliar. “I got to know Carl Bernard, a former province advisor in Hau Nghia Province, who was good pals with John Paul Vann.” Vann was a former US ranger who had served in Vietnam as a soldier and later as an advisor, and was among the harshest critics of the way the US conducted the during the Diem period. Bernard introduced him to Colonel Donald Marshall, another close acquaintance of Vann and a rare breed for the time – an officer with a PhD from a civilian university. (Note: It’s now common for career officers to have a graduate degree under their belt – it was almost unknown in the 50s.) Marshall was one of the team of military intellectuals that created a massive and very critical analysis of the US military’s conduct of the war for Army Chief of Staff Harold Johnson in 1965 entitled Program for the Pacification and Long-Term Development of South Vietnam (always called the PROVN Report). PROVN had been heavily influenced by the ideas of Vann many of which were already appearing in the American press via young journalists, and friends of Vann in 1962-63, including David Halberstam.

Halberstam’s book Making of a Quagmire remains a powerful picture of the early war and the “Vann Thesis.” PROVN echoed Vann that the US was losing the war because of the inability of US forces to “harness the revolution.” PROVN argued that the US military was fighting the “last war”, in this case World War II and Korea. The Vann argument, greatly expanded by PROVN, holds that the US army failed to win the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people because they did not realize that the Vietnamese peasantry was fighting a just revolutionary war against a corrupt government in Saigon: American support of Saigon had opened the door for a dangerous and ultimately self-defeating Marxist Revolution. The US, according to Vann, must quickly “harness the revolution,” which was ultimately a political and not a military endeavor. The stress on force obscured this all important fact the Vann/PROVN argument concluded. The realities on the ground were more complex however. Bergerud argues “Washington faced an incredible task after the assassination of President Diem by the South Vietnamese Army with US complicity. Diem’s apparatus, however weak, was the only anti-communist presence in most of Vietnam. The military junta that replaced it lacked any leader with vision and no political vehicle outside the already bad South Vietnamese Army. (ARVN) American leaders who had supported Diem’s overthrow (although not his assassination) faced the challenge of how to build a functioning government in a time of utter chaos and panic in South Vietnam. As Diem had failed, some American leaders began to conclude that the only major card to play was massive military aid. That was a futile wish in 1963. Two years later, with Saigon close to collapse, President Johnson, with nearly the full support of the State Department and Pentagon decided a direct US military intervention was the only way to avoid debacle.

WHAT WAS THE VALUE OF A PROVINCIAL STUDY?

Because revolutionary forces did not need to hold any point in South Vietnam, it was never possible for the American military to force the VC or NVA to battle. The result was a non-linear war where military or political action was directed at controlling population and territory. As Vietnam was organized into provinces, American and GVN efforts were inevitably based on the province (political efforts) or groups of provinces for military operation. (For instance, the US 25th Division had a “Tactical Area of Responsibility” [TAOR] of Hau Nghia, Tay Ninh and Binh Long provinces.) And of South Vietnam’s 43 provinces, Hau Nghia was considered one of the most important. It was a VC stronghold, with tremendous influence only 25 miles away from Saigon. Here was where much of the Tet offensive in the region was launched. It also was a rural Vietnamese province that lacked ethnic minorities or urban Vietnamese. It was exactly the type of area that Hanoi and the National Liberation Front considered the major theater of military and political struggle.

One of the big myths, one that was hard to shake for the US Army, was this belief in the revolutionary capacity of helicopters.

Therefore advocates of the Vann thesis like William Colby argued that any effort by the GVN with American support that could work in Hau Nghia could be exported elsewhere. The problem was that the Party controlled almost all of Hau Nghia province in 1965 and major military efforts would be required to begin the political struggle again. The US Army knew this and put the “village war” in a secondary position. (Note: CORDS – “Civilian Operations and Revolutionary Development Support” was ground zero for the US pacification effort: it was founded in mid-1967 under Robert Komer and taken over in 1968 by Colby. There was a lot of fish in the CORDS pond, but it’s safe to say CIA was a major school. Vann was a top CORDS official from 1967 until his death during the Easter Offensive in 1972.)

ON WESTMORELAND

President Johnson got what he wanted in his general, someone who would do what he was told. Remember, the Korean War and Truman’s firing of General McArthur for not following his orders was keen in the minds of the Johnson administration. He did not want someone to question him.

ON PERCEPTIONS OF THE WAR IN PROGRESS

John P. Vann was a career Army officer who served also in the Korean War. He was the only U.S. Civilian awarded the Distinguished Service Cross during the Vietnam War or since.

WESTMORELAND

“There are many reasons to criticize Westy. He was a man of courage, but his skills reflected the post-WWII Army and, sadly, he was a product of the system. But pacification, at least in theory, had his support as long as the village war did not interfere with major offensives. Indeed, he believed American military victories would greatly strengthen the efforts of the GVN and CORDS on the countryside. He wanted the South Vietnamese to lead it, because it would be better for them to take charge of these kinds of operations. But the South Vietnamese military was relatively weak. John Paul Vann argued that the US should have forced the South Vietnamese to reform their military. Fears of pushing around a smaller alley, indeed, looking like an imperial power did not matter to Vann. From his POV, everyone already considered the US an imperial power no matter what it did, and thus they should use their influence positively to get Saigon’s forces to improve and take more responsibility.

My advice for anyone attempting to study the Vietnam war is to capture the moment.

On the other end was William Colby, also a controversial figure. Colby wrote two very good books on Vietnam (Looking Back, and the other a broader view, Lost Victory). He believed US failure was rooted earlier than Vann argued. Colby was a bitter critic of the Diem coup and believed the US should not have supported it. Colby later wrote that it was inevitable and the VC would certainly capitalize on the resulting chaos. And as Colby predicted for almost three years, the South Vietnamese people were working without a central government and this allowed the guerrillas to redouble their strengths and gain an advantage that they never relinquished.

Bergerud commented, “The trouble is that Vann was also right: Diem was losing the war. If you read the early official histories of US involvement in Vietnam, including Ronald Spector’s Advice and Support: The Early Years, 1941-1960, and Richard Hunt’s Pacification: The American Struggle for Vietnam’s Hearts and Minds, one sees appalling picture of how bad things were. Sadly, there is much less written from the South Vietnamese political, cultural, and military POV to either support or challenge these works. But when I began my research, it dawned on me just how deep the hole in Vietnam was when we arrived. As far as I could discern, 1960 was about the last possible year something effective might have been put in play against the guerrillas or the Army of North Vietnam. In War Comes to Long An, Jeffery Race looked at Diem’s war on the countryside and showed how weak was the reed from the start. But the enemy too was not ready for all out struggle. The problem was that, before the early 1960s, Washington believed things were going well in Vietnam and was far more concerned with a number of other areas of the Cold War. With Cuba and Berlin drawing the attention of the American people and the Kennedy administration alike, only a very few Americans recognized that things were going sour in Southeast Asia.”

As Daniel Ellsberg noted in his excellent paper The Quagmire Myth and the Stalemate Machine no American president wanted a full scale war in Vietnam, but none would accept the concept of defeat. Therefore Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon all allocated the resources required to prevent defeat but were unwilling to take the dreadful risks needed to push for victory. The result was to keep the war effort at a level needed to keep South Vietnam going and hope that Hanoi would grow weary. If Hanoi did not, it remained vital not to lose the war during any given administration’s watch. Hence “Peace with Honor” in January 1973 kept South Vietnam alive, but allowed the North Vietnamese Army to stay in place inside the borders of South Vietnam.

THE NATURE OF THE WAR

Both sides created cardboard images of the Vietnam War during the conflict that perhaps reflected genuine belief or “spin.” The United States portrayed a war of aggression with NVN playing the role of North Korea and the US defending an ally. Washington often argued that the war was not an expression of genuine Vietnamese “nationalism” but a combination of aggression and subversion that twisted the nationalist impulse. Marxist historian Gabriel Kolko in his honest and keen book Anatomy of War: Vietnam, the United States, and Modern Historical Experience correctly mocks this idea. Whether one was on the politburo in Hanoi or a NLF supporter in the most humble Vietnamese village, everyone knew the nationalist/communist dichotomy was false. The ultimate aim was a “New Vietnam.” Gaining the new required both revolution in the South and reunification. So nationalism and revolution were equally necessary to reshape the nation. Yet Hanoi’s “puppet master” argument is also false. If the revolution wished a “New Vietnam” that put it at odds with anyone who found value in the Old Vietnam. Revolution thrills the young but brings fear and unease to many others. So there were genuine splits within SVN on ground of ethnicity, generation, relative status in rural society, religion (the Party’s anti-clerical stance was a constant sticking point in Vietnam and many other Third World Nations) and a genuine fear of harsh measures Hanoi was willing to employ to remake society. So it is true that corruption and social disorientation plagued the GVN. It is also true that ARVN lost more men in battle every year of the war except 1968 and often fought with surprising tenacity. A puppet army would have collapsed in the 1968 Tet Offensive and ARVN most certainly did not. So in the end, the Vietnam conflict, like so many conflicts that plagued the Third World after 1945 was a civil war. Over time those fighting for revolution showed more tenacity, often more skill and a willingness to pay a higher blood tax. Hanoi was stronger and better able to utilize fear, something that even many of its enemies realized. However it had no claim to superior virtue.

Two infantrymen from the 2d Bn, 27th Inf “Wolfhounds,” take a Viet Cong sniper under fire

in Hau Nghia Province during Operation “Kolekole.” (Photo by SP4 Joe Carey)

WAS VIETNAM A LOSS?

There’s a controversial revisionist thesis that has odd merit. It argues that in the long run, Vietnam was a strategic victory for the US. Not against the North Vietnamese, who won, but against the rise of communism in Asia. US support and defense against communist influence in Vietnam acted to slow expansion in other parts of Asia and the Third World. It is likely that American intervention in Vietnam forestalled Hanoi’s victory by almost a decade. If North Vietnam had won in 1966, it would have acted as a beacon for the revolutionary movements that existed throughout the Third World. A 1966 revolutionary victory in Vietnam might well have strengthened radical elements within the Chinese the Cultural Revolution. By 1975 it was clear in China that something was badly wrong. The “New Vietnam” was seriously fatigued and quickly involved in war with both (ironically) communist governments in China and Cambodia. When the dust had cleared “moderates” had prevailed in China and were willing to talk with the US. The 80s showed the beginning of what later became the major reforms that led a form of state capitalism in China and collapse in the USSR. Indeed, by 1995 America’s position in Asia was probably stronger than at any time in history. So, yes, the world would very likely have moved in a different direction had the US not intervened in Vietnam in 1965. But one can hardly rule out the possibility that the failure of revolutionary Marxism would have happened regardless. More to the point, nobody in the Washington in the early 1960s was considering the possibility that the US might lose the Vietnam War. Nobody had any idea how to win it, but as LBJ reminded the nation often, the USA did not lose wars. Any residual benefits from the Vietnam War, such as over one million amazingly productive new immigrants from Vietnam now prospering in the US, resulted entirely from the law of unintended consequences. Fighting a futile war that cost the lives of 50,000 Americans, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese, squandered treasure and humiliated the United States was not part the plan. It was and remains a dreadful chapter in Cold War history.

MYTHS AND FAILURES

One of the big myths, one that was hard to shake for the US Army, was this belief in the revolutionary capacity of helicopters. They believed it would square the circle of concerns over mobility in jungle warfare and be a panacea against the need for large amounts of boots on the ground. It is very true that the organized military wing of the revolution was crippled by 1970. But that result had nothing to do with the big operations Westmoreland launched in 1967. Instead it was the result of an incredible blunder by the NLF and Hanoi when they decided to push the “General Offensive” (often but inaccurately called the Tet Offensive) throughout 1968 and into mid-1969 and thus gave US and ARVN firepower major targets. The enemy made errors, just as we did, and the 1968-69 debacle was their worst. The furious fighting did, however, make it clear to Nixon that the US Army had to cut its manpower. Nixon hoped “Vietnamization” and pacification would take the place of US troops. It lengthened the war, but ultimately it was not enough. No war is perfect. And it sure as hell is not like chess. All analogy is dangerous, but war is much closer to poker, perhaps combined with the physical duress and limitations of football.” But he warns against the historian’s desire to write counterfactuals. “If you do, exercise extreme limitations on the chain of events you’re looking at hypothetically. Maybe there was something that could have been done in 1958 to help Diem. But the help would have needed to have been substantial. And in 1958 Washington saw no threat. So the US didn’t drop the ball in Diem’s time because in the real world we didn’t know where the ball was. Could the US have prevailed if we had taken much more dramatic actions against North Vietnam after 1965? Perhaps on paper they could have. But in the real Washington Johnson wanted no risk of Chinese or Russian intervention. With Korea and the Cuban Missile Crisis fresh in the mind, it was most reasonable restraint. Could Saigon have survived had Nixon not fallen due to Watergate? Perhaps if Hanoi believed the US would intervene again. But in the real 1974 the US Navy and the USAAF had withdrawn from Southeast Asia and the Army was struggling with serious problems. The NVA was inside South Vietnamese Central Highlands and the South Vietnamese government and economy were beginning to collapse because of the oil crisis simple fatigue. It’s hard not to think that after the cost borne that Hanoi would have abandoned the struggle. One can deeply regret the outcome of the Vietnam War, but it’s hard not to conclude that ultimately the Vietnamese Communist Party in Hanoi and their many supporters throughout Vietnam because they were willing to pay a price their opponents were not.

Trouble in the post-imperial world was inevitable. Vietnam was just one dramatic chapter in a very big story.

REGARDING THE RURAL POOR

John McAlister in his fine book The Vietnamese and Their Revolution argued that French imperialism and the modernity that accompanied it in the late 19th century destroyed the heart of traditional Vietnamese society. However, imperialists were not there to build nations but to build empires so little was left to fill the void. Vietnamese Marxists like young Ho Chi Minh also wanted a modern Vietnam, just one in the Soviet mold. This story in one form or another played out throughout the world dominated by Western Imperialism. But Western Imperialism was always flimsy at the base and collapsed with great speed once seriously opposed within the colonies by leaders like Gandhi and weakened by the world wars. I think it’s pretty obvious that that trouble in the post-imperial world was inevitable. Vietnam was just one dramatic chapter in a very big story.

ON THE DOMINO THEORY

During the conflict American opponents of the war used to laugh at the “Domino Theory.” But whatever Vietnam was, it was no delusion. The domino image was coined by Eisenhower, but the concept came straight from Lenin. You can see this in the various editions of Lenin’s famous pamphlet “Imperialism: The Highest State of Capitalism.” (Note: this was especially clear in the later editions for which Lenin included a new introduction. After the Red defeat in Poland, the point was pounded home even harder. In his last letters and discussions, Lenin was clearly entertaining the possibility that Europe’s colonies and not the immediate trials of the working class would ultimately trigger the demise of capitalism.) The Commenter, which included the nascent Vietnamese Workers Party, was a clear declaration that what was later called the Third World would become a major theater in the struggle considered justified, necessary and unavoidable between revolution and capitalism. If Washington feared a cascade of weak regimes falling to Marxist revolution it was a reasonable fear and fully anticipated by both the USSR and the PRC in their own way.

ON THE FAILURE OF PACIFICATION

Remember, the study of Vietnam is a form of autopsy. “Dissecting failure.” The need for answers coincides with a need to defend what was done or not done.

ON STUDYING VIETNAM

My advice for anyone attempting to write or study the Vietnam war is to capture the moment. The context of how and what these people thought at the time is critical, and should not be replaced with hindsight. Remember this dichotomy: For almost the entire war, America could not imagine it would lose; while, at the same time, they feared and grappled with what they believed was a real and rising threat in the third world. Thucydides wrote that men fight wars for “fear, honor and profit.” He was right, but do note the order in which the variables appear.

# # #

Regarding the failure of the “General Offensive,” there was an even bigger failure of the “General Uprising,” especially in Saigon (from what the few of us saw), but also seemingly far less successful everywhere else they expected it to support the General Offensive.

Our little group of 7 or so non-combatants was one of two small groups that went into Saigon during Tet 68 (to pick up our own guys stuck in town) and was led by an Air Force SSgt that had been a Marine serving in Cyprus (and Lebanon) in the late 50s or early 60s. He had us watching the reactions of the locals, and pointed out that those terrified people that would peek out of the windows were all afraid of us, but weren’t looking anywhere else but at us. A good sign he said, that it was unlikely for VC to be in the immediate area. He said the main thing we had to do was avoid getting between the VC trying to get out and reform. We were minimally armed, equipped, trained, or experienced enough to risk forcing even small groups of more experienced and desperate VC to fight us in an attempt to escape.

Our priority was getting our guy back to the air base, and we grew very confident even on the way in, more so on the way out. The former Marine SSgt probably had a better sense of what was going on and how to interpret information he could gather informally from Intel and USAID contacts he seemed to cultivate. I don’t remember if I heard the specific term, “General Uprising,” from him at that time, but his evaluation of the people they expected to join them failing to do so that day has withstood all tests of time for me.

Points I haven’t tested as much:

I believe the Communist hard liners were worse than all the Imperialist Capitalist hard liners on our side. Both tried to force their versions of ideal governments on the people stuck in the middle (though both made poor choices, Le Duan for the most powerful leader in the north, and Diem in the south, when Uncle Ho was the real people’s most moderate choice).

I do believe our far less than perfect efforts did at least result in us being among the most welcome nationalities in Vietnam once the dust settled a decade after the war ended, and that all of the major countries became more moderate, though not as moderate as many of us would still like. I had traveled around 60,000 miles, all over Vietnam and Thailand to 61 bases and camps that I could recall, and used to ask Vietnamese what they thought every chance I got. One family I had helped by stopping a drunk soldier chasing one of the daughters, gave me a Mot Dong note, the paper version of one Piaster, worth 1/87,000th of a penny last time I checked. Our Intel guys told me it was used as a secret form of recognition by VC, but a USAID worker (with 7 years in country) told me it was really more of a safe conduct pass for people trusted by most of the people stuck in the middle though nominally on one side or the other.

I like to think I sensed some of what I think Doug Ramsey learned after he was captured.