An Introduction to Mesoamerica

INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL E. SMITH

Editor’s Introduction

Maya calendar detail. Photo credit: Niciak

Today, many poor U.S. urban neighborhoods are described as “food deserts” where residents are not even able to purchase fresh meats and vegetables. A majority of the housing development projects designed for the lower classes have been stupendous failures. Other large cities, notably Detroit, are losing population and revenue; their governments are hoping to implement drastic schemes of “planned shrinkage” so that they can cut the costs of providing services to a spread out population. Many residents worry that their neighborhoods will be trashed and only the affluent will benefit from re-development. Using examples of urban places from the past expands the number of models that can be compared in order to study the effect of urban design choices on other social behaviors. The “Service Access” investigators are optimistic that their findings may better inform urban planners about effective options for creating self-sufficient, sustainable neighborhoods in the 21st century.

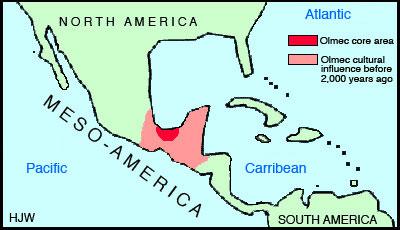

How did other nations, other cultures, and other states deal with these same problems? How were they successful for so many centuries in distributing food and water, merchandise and religion, to all sectors of society? One valuable glimpse into the question comes in an anthology of remarkable richness, The Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: A Reader, edited by Michael E. Smith and Marilyn A. Masson, a text widely used to introduce students to this most relevant field of study. Here we break down some of the anthology’s ideas and approaches in an interview with co-editor Smith and a review of the book.

Michael E. Smith is currently Professor at Arizona State University’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change. Prior to this appointment in 2005, he was Professor of Anthropology at the State University of New York at Albany. He received his doctorate from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1983. Smith has specialized in the archaeology of complex societies and is an internationally recognized expert on the Aztec civilization. His is the author of The Aztecs (2012, Blackwell Press) and Aztec City-State Capitals (2008, University Press of Florida), as well as many other books and articles on Mesoamerican archaeology and comparative urbanism.

For over 25 years, Smith has conducted archaeological research at numerous Aztec settlements. Aztec society (A.D. 1325-1521) is best known from historic documents dating to the era of the Spanish conquest. The immense Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan has not been particularly accessible to archaeologists because it lies directly beneath Mexico City, which covers most of the Basin of Mexico. Smith has been able to provide valuable insights to the organization of the vast Aztec Empire by studying settlements, both small and large, that had submitted to Aztec authority but were located some distance from the ancient urban center. Although the Aztec Empire has been usually characterized as a highly centralized totalitarian state, Smith has been able to demonstrate that many communities within its domain were able to maintain a

considerable amount of autonomy, especially in the economic sphere, and that the Aztec leadership was not all-controlling. Smith’s most recent archaeological project, “Organization and Empire at the Aztec City of Calixtlahuaca,” has enabled him to study the architectural principles and urban form at a major (317 hectares) provincial center, the third largest city in pre-Columbian central Mexico.

At Arizona State, Smith has also been involved in an ongoing, multidisciplinary project that explores ways to apply knowledge about ancient cities to contemporary urban issues. Smith and collaborators are presently working on a project called “Service Access in Premodern Cities,” which will examine how the organization of the built environment in a sample of pre-modern cities promoted or prevented equality of access to resources. Many U.S. cities today are characterized by segregation into neighborhoods defined by socioeconomic class, among which there are great disparities in the quality of educational, medical and recreational facilities.

Wikimedia Commons “15-07-13-Teotihuacan-RalfR-WMA 0230″ by Ralf Roletschek

Interview with Michael E. Smith

September, 2015

Tun-Quirigua-C

What three things would you like a general reader to take away from this work?

This book is a collection of scholarly papers about the ancient cultures of Mesoamerica. Some of the major lessons of the book would be:

- The ancient Mesoamerican cultures were highly diverse, in their social organization, economy, religions, and political organization

- In spite of that diversity, they were held together by trade and other contacts over long distances.

- The sizes, levels of complexity, and technical and social achievements of these cultures were comparable to the early states of the Old World, such as the Sumerians, ancient Egyptians, or Greeks.

What are the most common misperceptions students have about ancient empires like the Aztecs?

Many people think that all New World cultures were tribal peoples living in small groups, similar to the Iroquois and other tribal peoples encountered by the European explorers in North America. Even though the Spaniards who conquered the Aztecs and Incas described kings, roads, advanced technology, laws, and large urban settlements, westerners have often been slow to acknowledge the existence of these features and their implications for the levels of cultural development reached by indigenous societies in the New World.

For an issue like the economy of the Aztecs, there are two diametrically opposed misconceptions. On the one hand are people who follow the “tribal” interpretation I just mentioned. They see the Aztecs as having a very simple and small-scale economy. They say that when the Spaniards described money and marketplaces, they were mistakenly applying their concepts from Spain to the Aztecs. Yet we now know that the Aztecs had two form of money (cacao beans and cotton textiles), they traded in periodic marketplaces, and there were professional merchants and craft producers. But these observations lead to the second, opposed view, which says that the Aztecs had a modern-type capitalist economy. The problem with this interpretation is that the Aztecs lacked wage labor and had a low level of private property in land. Without wage labor, you do not have a capitalist economy.

What common elements exist between Mesoamerican urban centers like Tikal and Monte Alban and modern cities? What specific lessons should the rising generation keep in mind as they look at the shaping of cities in the 21st century?

Ancient Mesoamerican cities share a number of characteristics with contemporary cities. They were concentrations of population within their society, and that brought with it both benefits (e.g., more information transfer, busier economies) and problems (more poverty and crime). That fact also created the need for neighborhood organization in ancient and modern cities. As central places, cities were and are places of concentration of political power, wealth, economic activity, and cultural activities.

What would the designers of Tenochtitlan say if they could see Mexico City today?

Very interesting question. I would guess that they would be shocked at the size of the city, the number of people and density of settlement, and or course they would be surprised at the changes in technology, architecture, transport, etc. But I’d also think that the basic downtown city would still look somewhat familiar to them. The city follows the original Aztec grid, and the ceremonial center is still in the same place.

A modern city (Toronto) with grids similar to Aztec cities. Source: Wikimedia Commons by Skeezix1000

Which ancient cities would a modern urban theorist like Victor Gruen or Richard Florida like or dislike?

I am only familiar with a few of the works of these authors, but I would think they would like the low-density cities of the Classic Maya. There was more “green space” than buildings, and lots of urban agriculture. People lived in local communities (neighborhoods or clusters) of a reasonable size, knew their neighbors, and probably watched out for one another.

Which city has sharper class divisions – New York City today, or Teotihuacan?

No contest: New York City. Teotihuacan was a remarkable pre-modern city in that wealth differences were quite small. Most people lived in luxurious houses (the so-called apartment compounds), and wealthy people lived in houses only slightly bigger than most.

The book makes the point that not all Mesoamerican societies had the same kind of sociopolitical structure. How were these societies alike, and how were they different?

In many ways, the local forms of social organization – households, communities, villages, neighborhoods – were very similar among the various Mesoamerican societies. There were two major kinds of differences in political structure. First, societies differed in the size and form of government, from small city-states to large territorial states and empires. Second, they differed in their level of autocratic vs. collective government. This is a topic that was not well understood when our book was published, but it has seen a lot of work in recent years. One major contrast, for example, was between the autocratic Maya kingdoms (where kings exercised lots of power, yet left local communities alone to run their own affairs) and the more collective state at Teotihuacan (where we can’t even tell if they had kings or not, yet the regime reached further into local society).

BOOK REVIEW

The Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: A Reader

Edited by Michael E. Smith and Marilyn A. Masson

Wikispaces/TES Global

As a general reader, I can see three reasons why The Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: A Reader is so highly regarded in the field. First, the writing in this anthology of scholarly essays — while challenging — is almost always accessible. The 23 authors collected here are able to explain their findings and theories and comparisons in language that is fairly straightforward. Second, the content is rich and varied: the anthology essays range in subject from kingship to urban design to corporate economics to war to art and “galactic polities.” The two editors, Michael E. Smith and Marilyn A. Masson, consciously chose “articles that presented new and interesting data and conclusions.” Third, the editors step forward to introduce each of the four sections – society, economics, politics and religion – and in doing so weave together the disparate parts into a true anthology. The collection captures some of the dramatic scholarly advances made in the second half of the Twentieth Century, the most dramatic being our ability to read Mayan writing for the first time (thanks to David Coe’s 1992 work Breaking the Maya Code).

An example of the writing can be found in my favorite essay in this vibrant collection, Joyce Marcus’ “On the Nature of the Mesoamerican City.” The essay starts with this sentence:

One of the most spectacular settlement types of pre-Colombian Mesoamerica was the city.

This is an understatement. To a modern apartment dweller like me, the scale and scope of urban centers like Teotihuacan, Monte Alban, Calakmul and Tikal are amazing. Joyce Marcus pops the hood on these ancient cities and finds a rich complexity beneath the impressive appearances. Three-hundred-unit apartment complexes and multi-acre housing compounds were common. Raised causeways 60 meters wide and four miles long transported goods for what amounted to large-scale corporate trade. Systems of moats and earthworks bordered the cities, to protect against invaders. Perhaps equally impressive, the surrounding farmland needed to support an urban population was strictly managed.

Mesoamerican cities do not resemble one another so much as they share more universal qualities with other cities in other times, other lands.

Aztec warriors brandishing clubs with obsidian blades Wikimedia Commons: Field Museum

The author does not end where she starts. “I began this paper,” she writes, “with the notion that ‘each city is unique in detail but resembles others in function and pattern.’” Instead, she discovered that Mesoamerican cities do not resemble one another so much as they share more universal qualities with other cities in other times, other lands. One of these universal aspects is class. The city ruler’s palace marked a promontory point, surrounded by public buildings, religious plazas and elite residences, which in turn border working class neighborhoods, and so on. She marks the presence of the spiritual world – street of the dead, temples, a pyramid of the moon side by side with industrial workshops and markets – among the homes and stores and workshops. The author contrasts various modern urban models, including concentric (radiating outward from a central plaza), sectored, and multiple-nuclei models. She discusses what she calls “hyperurbanism,” namely that there were no cities of intermediate size – either a super city with a population of 200,000 or a large village of 3,000.

Another topic brought to full light in this excellent collection of scholarly essays is industry and trade in the Mesoamerican societies. In a Chapter Nine essay on regional trade, Frances F. Berdan opens with this powerful image:

Trade in Aztec Mexico consisted of long caravans of professional merchants — merchants laden with precious goods, merchants trekking through dangerous and hostile country, merchants concluding glamorous transactions with rulers of distant states … this is the usual twentieth-century image of Aztec trade. But it is a skewed and incomplete image.

The full image (which the author goes on to describe) includes diverse levels of trade in salt, cotton, cacao, maize, fish and more, from the rulers’ palaces down to the commoners’ households. Another essay delves into the obsidian industry, which manufactured and distributed countless tools and weapons made from the black stone throughout the Aztec empire and upheld dynasties in doing so. We discover that the industry surrounding obsidian was comparable to the auto industry in Detroit — a sprawling, inclusive complex enterprise consuming entire city sectors. Its manufacture, sale and distribution reached far abroad.

One caution the editors give is our tendency to generalize. “There were hundreds of separate languages and a great deal of social and cultural variation within Mesoamerica,” writes the editor, and we need to pick our way carefully among the many tribes and villages of these large societies.

In a recent article entitled “The New Histories,” (Harvard Magazine, Nov. Dec. 2014), historian Sven Beckert, co-Director of the Weatherhead Initiative in Global History, points out the value of a global perspective. “History looks very different if you don’t take a particular nation-state as the starting point of all your investigations.” He argues that trying to understand the past solely within the confines of national boundaries misses much of the story. In particular, the narratives of the Southern hemispheres can get overlooked while Western narratives prevail. This is all the more reason for us to look to a gem of a collection like The Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: A Reader.

History looks very different if you don’t take a particular nation-state as the starting point of all your investigations.

We’re all Mayan now. Today we are witnessing global population shifts, not only from the Middle East to Europe but also from Mesoamerica to North America. Former citizens of Xochicalco and Zacatecas are now citizens of Minnesota and Oregon and Halifax. Citizens of Mesopotamia are now living in Stockholm and Hamburg and Cardiff. We all need to know Persian myths. The histories which underpin these once-separate cultures are so different, and now they are an important part of our common heritage. This anthology of essays on Mesoamerica provides challenging, valuable reading on a most timely topic for all of us.

Detail of folio 23r from the Codex Mendoza. Tribute from towns of the Province of Quauhnahuac: name-glyph of ‘Yztepec. pueblo’. The name means ‘On the Hill of Obsidian’, and the town’s glyph is an obsidian blade on top of a hill. The Bodleian Library Oxford University

Detail of folio 23r from the Codex Mendoza. Tribute from towns of the Province of Quauhnahuac: name-glyph of ‘Yztepec. pueblo’. The name means ‘On the Hill of Obsidian’, and the town’s glyph is an obsidian blade on top of a hill. The Bodleian Library Oxford University

###